Japanese intellectuals in the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868) did not normally have the opportunity to learn about Christianity because of the regime’s self-isolation (Sakoku) policy. This policy restricted foreign trade and forbade the propagation of Christianity in Japan. The Tokugawa regarded European Christian missionaries as subversive to their own hegemonic political rule.

The regime was dominated by the ideas and ethics of Confucianism, particularly among intellectuals. Confucianism was derived from the ideas of the Chinese thinker Confucius (551 BC-479 BC) who emphasized the importance of continuity between past and present. The philosophy and scholarship of Confucianism stressed the righteous behavior of every individual, behavior which was seen as contributing to the formation of the ideal society and social order. While many aspects of Confucian moral thought may resonate with Christian readers, Confucian thinkers had a starkly different concept of God than that proposed by Christianity.

However, the isolationist, Confucian culture did not last forever. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) demanded Japanese ports open. Overwhelmed by American naval powers, the Tokugawa regime forsook the Sakoku policy and opened two ports to the U.S. This event destabilized the Tokugawa regime, and the Meiji government replaced the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868. The new government endeavored to modernize Japan by adopting Western ideas and technology. Eventually, on February 24, 1873, the Meiji Government lifted the ban on Christianity because of diplomatic pressure from Western powers. Since then, Western Catholic and Protestant missionaries have worked to evangelize Japan. This has meant that Japanese intellectuals have been able to learn about Christianity. However, it was not easy for those who were educated within a Confucian framework informed by Japanese custom to become convinced of the truth of Christianity.

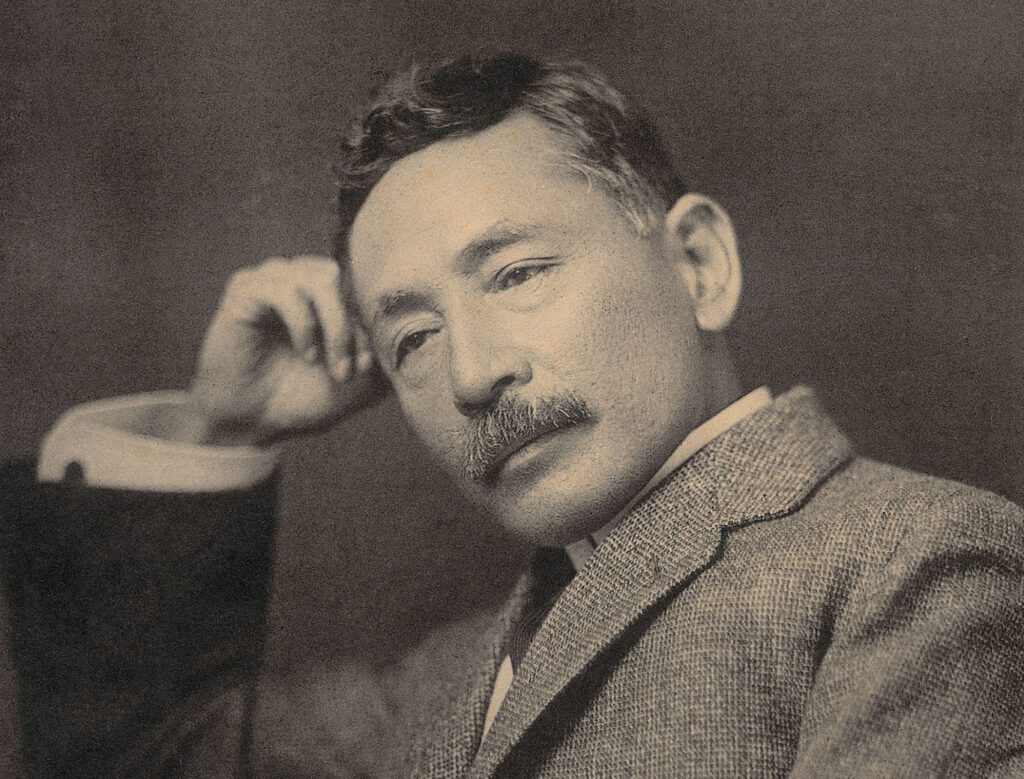

In this piece, I would like to consider an example of a prominent Japanese intellectual, Soseki Natsume (1867-1916), who engaged with Christianity but struggled to fully come to grips with it. Natsume, a novelist and critic, wrote works that wrestled with themes such as sin and responsibility—pieces that are indebted to his experiences with Christianity. However, his explicit engagement with Christian sources reveals some of the errors to which Japanese intellectuals formed by Confucianism were prone. Perhaps the most illuminating example, which we will examine, is how Natsume responded to the work of St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890), a distinguished Catholic convert and apologist against secularism in the nineteenth century. In arguing against Newman, Natsume failed to grasp the latter’s notion of the “illative sense.” If he had understood this sense, he would have had a better understanding of how one changes one’s mind, and thus of conversion and of Christianity itself.

Soseki Natsume and Christianity

As Natsume was born in Edo (today known as Tokyo) in 1867, just a year before the Meiji Restoration, he was brought up in the embryonic stage of Japanese Westernization. He studied both Chinese classics and English in his youth, ultimately majoring in English literature at the Imperial University. He even lived in London from 1900 to 1902 in order to study English Literature. After returning to Japan, he eventually became a writer at The Tokyo Asahi Newspaper. Today, though, he is perhaps best known for his novels, including Sanshiro (1908), And Then (1909), The Gate (1910), and Kokoro (1914).

While in England, Natsume recorded his negative impression of Christian missionaries and the experience likely influenced his attitude toward Christianity. During his journey, he contacted European Christian missionaries who had spent time in China. Naturally, they tried to convert him to Christianity, but he thought that their explanation of incarnation was unreasonable. He wrote,

Those dear souls are in full conviction that they are iconoclasts; at the same time, they do not hesitate in saying Christ is the incarnation of God. God can only have a meaning to them through Christ. God in itself in its absoluteness is not sufficient for their sensual intellects to form a clear conception of God through Christ. God in its incarnation is necessary for their belief to form a palpable ground to rest on. Is not this, in a sense, an idol-worship?

Despite this accusation of idolatry, Natsume did not reject Christianity as simply false and harmful. He regarded it as a grand religion, but he found the missionaries’ claim that they possessed truth to the exclusion of other faiths foolish. He said,

I have no grudge against Christianity, on the contrary I firmly believe that it is a grand religion, and those who can find faith in it, are surely saved by it. Meanwhile, those whom they call idolaters can likewise find salvation in their way of worship, never so gross, provided they have good faith in them. Religion is after all a matter of faith, not of argument or reason.

Natsume was a religious pluralist, and thus saw no need to convert to Christianity. He felt the oneness of existence acutely and believed that neither heaven nor hell could exist. To put it simply, Natsume would have greatly appreciated John Lennon’s song “Imagine.”

When an English woman asked him why he did not pray, he replied that he did not know to whom he prayed. The lady was moved enough to weep. She said she would pray to God for him and asked him if he could make a promise to her. Touched by her great sympathy for him, Natsume agreed. The promise was that Natsume would read the Gospel. At the end of his diary, he wrote, “On my departure, she reminds me to keep the promise. So, I will read the Gospel.” He kept his promise and endeavored to study Scripture.

The illative sense: Newman, Crozier, and Natsume

The four Evangelists were not the only Christian authors with whom Natsume engaged. St. John Henry Newman was one of the most prominent English Catholics of Natsume’s lifetime, so it is natural that the latter would feel the need to explore his thought. While today better-known for his autobiography Apologia Pro Vita Sua and his views on education expressed in Idea of a University, Newman’s most substantive philosophical text is An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, and it is this work that interests us.

The Grammar of Ascent is not an easy text to read and understand, let alone summarize. In it, Newman aims to elucidate how it is that man comes to affirm that something is true. This includes not just seemingly simple statements like “human beings are mortal,” but it also (and crucially) includes the claims of religion.

In explaining how man gives his ascent, Newman introduced the idea that each rational human being possesses something he terms “the illative sense.”

He explained that it implies that a person reasons from data using human faculties. This means that two persons can reach different conclusions if they use the same data and evidence. One person deduces from his moral sense the presence of a Moral Governor, and another does not. In each case there may be an exercise, and a sound exercise, of the illative sense, but one recognizes the principle of conscience in his moral sense, and the other does not recognize it. The illative sense of the one is employed upon, and informed by, the emotions of hope and fear and the sense of sin, whereas the other discerns the distinction of right and wrong in no other way than he distinguishes light from darkness, or beauty from deformity. Newman concluded that the former has the Religious Sense and the other has the Moral. In this way, he suggested that personal sensibility for feeling hope, fear, and sinfulness, plays a critical part in leading one to faith in God or not.

We possess a note (likely written sometime between 1901 and 1906, either during or shortly after his time in Britain) in which Natsume discussed the illative sense critically. However, he failed to understand the illative sense’s relationship to the affirmation of religious claims. It is likely that Natsume never actually read the original text of An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, instead relying on Civilization & Progress by John Beattie Crozier (1849-1921). This work, a copy of which Natsume annotated, referred to the illative sense without explicitly engaging with Newman’s original text at all. Thus, Natsume’s understanding of the illative sense was formed by the perspective of Crozier, who, in a single chapter, introduced Newman’s idea and criticized it. Influenced by Charles Darwin’s and Herbert Spencer’s theories of evolution, Crozier argued that the history of civilized peoples can be viewed from a scientific viewpoint informed by the laws of progress.

In his treatment of Grammar of Assent, Crozier wrote that Newman’s first object in the work was to dethrone modern science as the supposed path to the highest truth, and this much, at least, is true. He then argued that Newman was attempting to replace science with his own new path named the illative sense. To challenge Newman’s position, Crozier advocated for the view that the uniformity of the laws of Nature alone enable man to give a full, unreserved, and legitimate assent to the conclusions of modern science in the face of facts and doctrines that are in real or apparent opposition to them. He interpreted Newman’s illative sense as an alternative to applied science. Therefore, in his view, the illative sense can have no more authority than science. The illative sense, in Crozier’s interpretation, is described as the art of a doctor who detects the nature of a disease by a kind of intuition, or a general who overpowers or outwits his adversary and wins the battle. He claimed that Newman would revive all forms of supernaturalism disguised as the illative Sense in the concluding part. As he put it,

And so Cardinal Newman, having thrown out Science at the beginning of his book on account of the havoc it was making with religious creeds, and all forms of supernaturalism, is obliged to bring it back again at the end, disguised as the ‘illative sense’. Indeed, that a man of Cardinal Newman’s immense intellectual powers in this nineteenth century-dream that there can be any organon of truth but Science, physical and mental—which is only organized experience of all kinds—is only another instance of how the pure intellect is deflected from the truth by the longings and desires of the heart.

We can begin to see, then how Natsume, who encountered the idea of the illative sense through the lens of Crozier, easily fell into misinterpretations of it. It is useful, though, to look at his own words about the illative sense. In his note, he provided a sort of phenomenology of a scientist’s experience of the illative sense as interpreted through the lens of Newman,

Newman’s Illative Sense? Before a scientist set[s] to investigate a problem there is a dim and half unconscious sense of feeling, this is so or this may be so etc. Which becomes clearer and clearer step by step as the investigation proceeds (or ends in failure). This sense starts with the nondescript sense of dissatisfaction. A certain feeling of imperfection which attacks us when we are brought face to face with the present system. This may be caused by weariness consequent on repetition, especially in the domain of art and literature. When a new way is not struck out, we rove in this dark till we see a new light. Religion, philosophy, literature and art.

As we can see, Natsume interpreted the illative sense as something of an inquisitive spirit which invigorates scientific investigation. He thought that it arose from a certain feeling of the imperfection of the present system of scientific investigation, in particular, that weariness followed from the necessary repetition. In the final, frustratingly terse, line of the note, he seems to imply that religion, philosophy, literature, and art could be renovated by application of the illative sense.

After this passage, Natsume moved on to claim that Japanese people find it difficult to use the illative sense, both in Japanese and English, and to consider why this is the case. “No matter how we are weary,” he writes, “there exist many things on earth that we are not able to control. Natural law of thought and nature [sic]. General people seem to accept them gladly. However, observing these laws as well as other things makes me boring.”

People in feudal times observed Confucius and Mencius ethics because they could not know how to resist them. They cannot help resigning themselves to accept them. Japanese and Chinese people ought to enlighten themselves in the same way. The people in both countries are forced to change. But they are not willing to change. If possible, they would like not to change.

Natsume argued that the reason Japanese and Chinese people struggle with the illative sense is that they have a basically passive character. Historically, when they were driven to observe Chinese ethics or accept Western civilization, they did so because of external surroundings and forces, not on account of any personal initiative. He implies, then, that both Japanese and Chinese people are unlike both Western conservatives and radicals, who chose their positions using their own initiative by making use of the illative sense.

In relating this context, he said in the lecture in Wakayama in 1911 that the social changes in modern Japan were all stimulated from outside rather than from within and merely “skimmed the surface.” Natsume’s note on illative sense and his comment on Japanese modernization are critical for understanding how he interpreted modernization in Asia.

Soseki Natsume, sin, and redemption

Natsume, as previously noted, felt he could not accept Christianity on logical grounds. Perhaps relatedly, he misunderstood the relevance of the illative sense to religious sense. However, this does not mean that he was not deeply impacted by Christianity and even Newman’s account of the illative sense. Intriguingly, he wrote a novel entitled Kokoro in his later years that focuses on the sense of sin experienced by a Japanese intellectual. Published in 1914, the novel tells the story of Sensei, a good-natured man who takes care of his friend, Mr. K. in his student days. Both of them live in the same boarding house and fall in love with the same woman, the daughter of the widow who runs the boarding house. This causes Sensei great agony. However, Sensei ultimately betrays his friend to win the daughter’s love and marries her.

Later, Mr. K commits suicide, but he does not leave a suicide note. Sensei is wracked with guilt, believing himself to have caused this suicide, and he is constantly terrified and tormented by an acute sense of his own sin. He begins to imagine Mr. K standing beside his wife, staring at Sensei. He unfailingly visits Mr. K’s tomb each month, but he finds no solace in this. Instead, his sense of sin and its weight becomes increasingly stronger. This novel engages seriously with the dark side of man’s inner life, and reading it can benefit greatly from understanding Natsume’s study of Christianity. As one of the novel’s many descriptions of Sensei’s awareness of sin reads,

From then on, a nameless fear would assail me from time to time. At first, it seemed to come over me without warning from the shadows around me, and I would gasp at its unexpectedness. Later, however, when the experience had become more familiar to me, my heart would readily succumb—or perhaps respond—to it; and I would begin to wonder if this fear had not always been in some hidden corner of my heart, ever since I was born. I would then ask myself whether I had not lost my sanity. But I had no desire to go to a doctor, or anyone else, for advice. I felt very strongly the sinfulness of man. It was this feeling that sent me to K’s grave every month that made me take care of my mother-in-law in her illness and behave gently towards my wife.

Fr. Peter Milward (1925-2017), who worked for Japanese citizens for many years both as a Catholic priest and professor at Sophia University, in discussing Kokoro observed that Sensei refers to the world as “this dark of ours,” and that he was subjected to the power of evil in a very real way. Thus, Fr. Milward argues, Natsume’s novel is seriously engaging with the Christian sense of the Devil and his power over the world. Natsume was deeply aware of man’s guilt over sin and his fear about its consequences. However, because of his failure to understand the experience of coming to faith (as Newman’s illative sense describes), he was unable to recognize a way out of this sense of sin.

Natsume never became a Christian. However, he learned from the Western Christians he met in London and from his exploration of the faith. His late work engages deeply with Christian concepts of sin, even if it lacks the Christian promise of forgiveness and redemption. His works, we might say, stand on the threshold of faith.