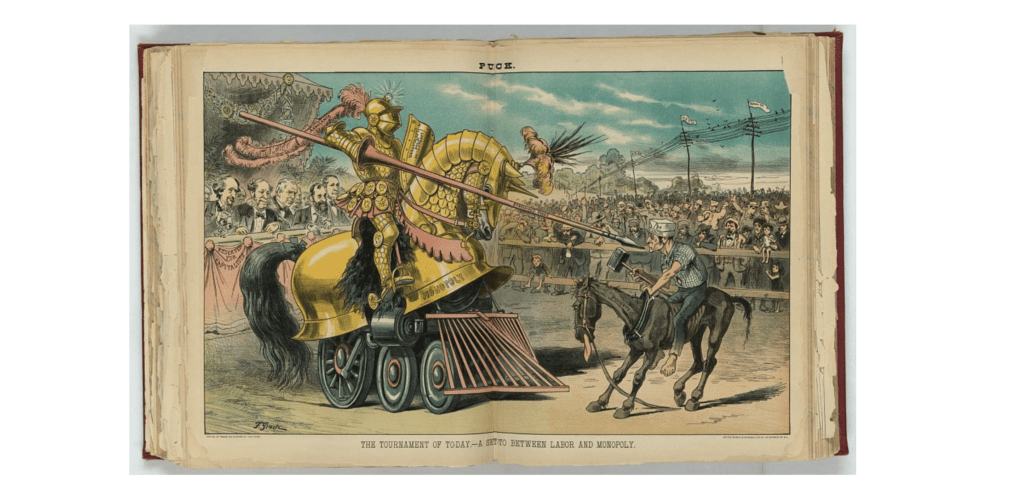

“The tournament of today—a set-to between labor and monopoly” (1883), a political cartoon by Friedrich Graetz (ca. 1840-ca.1913).

Several prominent American right-wing intellectuals, such as Sohrab Ahmari, Patrick Deneen, and Adrian Vermeule, over the last few years have elaborated the idea that the state apparatus should be used to promote the ‘common good,’ advocating also the greater role of the state in economic matters. Some Republican politicians adopted these ideas, provoking a backlash from traditional “small government” conservatives.

Due to the predominance of the Anglosphere in today’s world, debates about conservative philosophy are greatly distorted. For instance, there is a widely held belief that conservative advocates of state intervention have ‘leftist’ economic views. This is reflected by the fact that in the UK an important difference between the Labour Party and the Conservative Party until recently was their respective positions on economic issues, just like in the U.S. between Republicans and Democrats.

Patrick Deneen’s view in Why Liberalism Failed—that classical liberals (which he considers mainstream Republicans to be), as much as progressive liberals, are responsible for the collapse of traditional values and social institutions—leads him to see Anglo-conservative views on the role of the state and the freedom of the market as an aberration from the wider conservative tradition. Deneen states:

The proponents and heirs of classical liberalism—those whom we today call ‘conservative’—have at best offered lip service to the defense of ‘traditional values’ while its leadership class unanimously supports the main instrument of practical individualism in our modern world, the global ‘free market.’ This market—like all markets—while justified in the name of laissez-faire, in fact depends on constant state energy, intervention, and support, and has consistently been supported by classical liberals for its solvent effect on traditional relationships, cultural norms, generational thinking, and the practices and habits that subordinate market considerations to concerns born of interpersonal bonds and charity.

Indeed, why should a policy of unlimited free trade and ‘small government’ per se be conservative? Theoretically, if such a policy leads to an increase in anti-traditional behaviors—for instance, an increase in drug addiction, divorce rates, community collapse, large-scale emigration, etc.—surely it should not be called conservative. Of course, it may also lead to other outcomes, which mainstream American conservatives usually implicitly assume.

The differences between the European tradition and the Anglosphere are illustrated by their respective views of the rural way of life, which is usually hailed by the majority of conservatives. As historians write:

In the United States, the farmer was praised as an individual (farmer and not peasant, which has different implications in the English language). This individual aspired to respect competitive capitalism’s established norms against the monopolistic tendencies of large corporations and the railroad companies. In Europe, broadly speaking, the ruralist discourse placed the rural community at centre stage (and not the individual to such a large extent), exalting a way of life and certain values within it, and behind this, economic activity.

These differences are rooted in different patterns of historical development. While the American farmers occupied the wide territories given to them by the state and were a kind of affluent mini-feudalists, European peasants lived as serfs for hundreds of years. During urbanization and de-ruralization in the 19th and 20th centuries, many impoverished peasants moved to the cities. They were at least temporarily economic losers of the disruption caused by capitalism. Their traditional economic structures, such as the cooperatives in Eastern Europe that provided a certain level of self-sufficiency and security, fell apart.

Otto von Bismarck, whom some characterize as a conservative, in the 1880s introduced a set of laws for the protection of workers (Health Insurance Bill of 1883, Old Age and Disability Insurance Bill of 1889, etc.), usually considered as the birth of the welfare state on the continent. This is partly a reflection of his Junker (Prussian landed nobility) paternalism towards the lower classes. Furthermore, Bismarck’s trade policy was largely a protectionist one. With various protectionist measures, he tried to preserve the agrarian population as much as possible—first of all, his own class, namely the Junkers, but also the peasants who were the primary supporters of his government.

Such economic thinking is not unique to conservatives connected at least partially to the premodern way of life in the interwar period, for practically all right-wing options on the European continent advocated a certain level of state interventionism, as well as the strengthening of workers’ rights. These were also ‘anti-communist’ measures in order to suppress any appeal of the increasingly strong communists to the working class. It was not only fascist parties, such as the Hungarian Arrow Cross, which were strongest precisely in industrialized impoverished urban areas, that advanced interventionist policies, but also mainstream conservatives.

Historian Ivan Berend, in his book Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe Before World War II, describes the situation in Eastern Europe in the 1930s, in which, with the exception of Czechoslovakia, conservative authoritarians were in power.

The gold standard and laissez-faire were dead in Central and Eastern Europe, but strong, interventionist states were emerging. Governments assisted agriculture in overcoming the collapse of prices and instituted price support for grain and other agricultural products. High levels of internal debt were forgiven for farmers, and tax rates were lowered to ease the burden on agriculture. In all of these countries, partially or totally state-owned purchasing and sales organizations were created.

Part of this aspect of conservatism was also criticized by one of the most prominent liberals of that time, Friedrich Hayek, in his famous essay Why I am Not a Conservative. He claimed that conservatives are just as responsible as socialists for the persistence of economically illiberal policies:

That the conservative opposition to too much government control is not a matter of principle but is concerned with the particular aims of government is clearly shown in the economic sphere. Conservatives usually oppose collectivist and directivist measures in the industrial field, and here the liberal will often find allies in them. But at the same time conservatives are usually protectionists and have frequently supported socialist measures in agriculture. Indeed, though the restrictions which exist today in industry and commerce are mainly the result of socialist views, the equally important restrictions in agriculture were usually introduced by conservatives at an even earlier date. And in their efforts to discredit free enterprise many conservative leaders have vied with the socialists.

In the aftermath of the World War II, Christian Democrats were the primary force in the creation of the European Union. During the signing of the European Coal and Steel Organization, the forerunner of the EU, foreign ministers of all five signatory countries (Belgium, French, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany) were Christian Democrats. Back in the 1970s, the Swedish Social Democratic Prime Minister Olaf Palme would say that the European Community can best be described with the four ‘C’s: “capitalist,” “conservative,” “colonialist,” and “clerical.” Christian democratic governments, to the same extent as social-democratic governments, created a strong welfare state in Europe—but for different reasons. While social democrats were fed by variations of Marxist thought, the social teaching of the Catholic Church served as a model for Christian democrats.

By the end of the 20th century, however, most right-wing political options had adopted a fairly free-market, pro-capitalist rhetoric. This sudden shift suggests that this policy is not inherent to conservative political thought, but rather that it came about on situational and historical grounds. Political scientist Michael Freeden explains these economic policy transformations, stressing that the outcome was what mattered most:

What seemed to its castigators an opportunistic ideology was in fact a highly consistent one. Even the ostensibly radical social transformation engaged in by Thatcherites was intended to re-establish the kind of natural organic change that, in their view, had been undermined by over-generous welfare measures and by trade union politics.

Thatcher’s views on economic issues are very different to that of the new Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who recently said: “No to mass immigration! Yes to jobs for our [compatriots]! No to big international finance! No to the bureaucrats of Brussels.” If we remove from that quote the references to mass migration and Brussels, a socialist politician from any corner of the world could say that. However, we can see from Meloni’s famous campaign speech that her criticisms of capitalism are conditioned mainly by the fact that, according to her, modern globalized capitalism destroys traditional national and religious identity, and the community in general:

Why is the family an enemy?… Because it is our identity … so they attack national identity, they attack religious identity, they attack gender identity, they attack family identity. I can’t define myself as Italian, Christian, woman, mother. No. I must be citizen x, gender x, parent 1, parent 2. I must be a number. Because when I am only a number, when I no longer have an identity or roots, then I will be the perfect slave at the mercy of financial speculators. The perfect consumer.

These words express what is behind the voting outcome of the last Italian parliamentary elections. The right-wing coalition gained proportionally more votes from the working class than from other groups. Strong conservative credentials can be found with both Thatcher and Meloni, which suggests that economic policy is not of primary concern in conservative political approaches. Rather, economic dogmas are only of primary importance for ideologies that reduce man to homo economicus—namely libertarians and communists. For others, economic policy is just a means to an end. If such policy does not produce a conservative outcome, it is not conservative.