There has been a lot of bad economic news lately, including an inevitable recession in Europe. I have advised legislators to prepare for an impending economic downturn.

That advice still stands. At the same time, there is also good news out there, partly in the form of declining inflation which will help make the coming recession a milder and shorter one.

America offers even more and better economic news, and it is highly relevant for Europe. On the one hand, given the sharp downturn in business investments in the fourth quarter of last year, the U.S. economy also looks destined for a recession. On the other hand, the numbers for inflation and unemployment in January suggest that the recession will be short and mild.

Even better: all the relevant data suggests that America has narrowly avoided falling into a destructive trap of stagflation. But the best news of it all is that we have new research showing exactly how that happened—and that it is well within the powers of Europe’s central banks and governments to follow America on the narrow path back to price stability and economic prosperity.

It should come as no surprise that the good economic news begins in America. Inflation in the U.S. economy topped out already this past summer, a full six months before Europe turned that corner. The so-called inverted yield curve on American government securities, which emerged late last year, is in large part an expression of investor expectations that inflation will be back to ‘normal’ levels in the near future.

While I maintain that both Europe and America will be in a recession this year, I share in the optimism about inflation. It is hard to make precise predictions about how the euro zone will return to price stability, due in large part to major differences across the currency area. Latvia has the highest inflation rate at 21.6%, with Spain at the very opposite end (5.8%). However, the overall trend toward lower rates is there, and will continue.

The U.S. inflation rate is on a more steady track downward and will probably be below 3% by the end of the summer. Europeans should take comfort in this decline: America has been ahead of Europe throughout this inflation episode. It was first with high inflation and reached the peak a full six months before Europe did. That alone is a reason to expect lower European inflation rates in the spring and the summer.

There are more solid reasons as well, especially in the new research mentioned earlier. Before we get there, though, let us recognize that many factors can make Europe deviate from the path to lower inflation that America is currently on. Many variables under European control, so to speak, may keep inflation elevated for an extended period of time. Those variables are practically all policy related, which means that policymakers do have real influence over inflation. Central banks in Europe are already doing their share, responsibly increasing interest rates; legislators can join them in bringing down inflation by, among other things, abandoning bad ideas such as the transition from cheap, affordable energy to expensive ‘green’ alternatives.

If they insist on policy measures that can reignite inflation, Europe is very likely to fall into the abyss we know as stagflation. For those who want to avoid that end station, it is encouraging to see that stagflation is not inevitable: the American economy has just narrowly avoided the combination of high inflation and high unemployment.

We know why and how, which means that Europe can do the same.

To see how America steered clear of stagflation, we first need to examine the phenomenon itself. Economists have been worried about a return to stagflation since its ugly appearance in the late 1970s and early 1980s. That episode fell into public oblivion during the long period of price stability from circa 1985 to 2015, but it has lurked in the academic literature and popped up from time to time at professional conferences, specifically related to monetary policy.

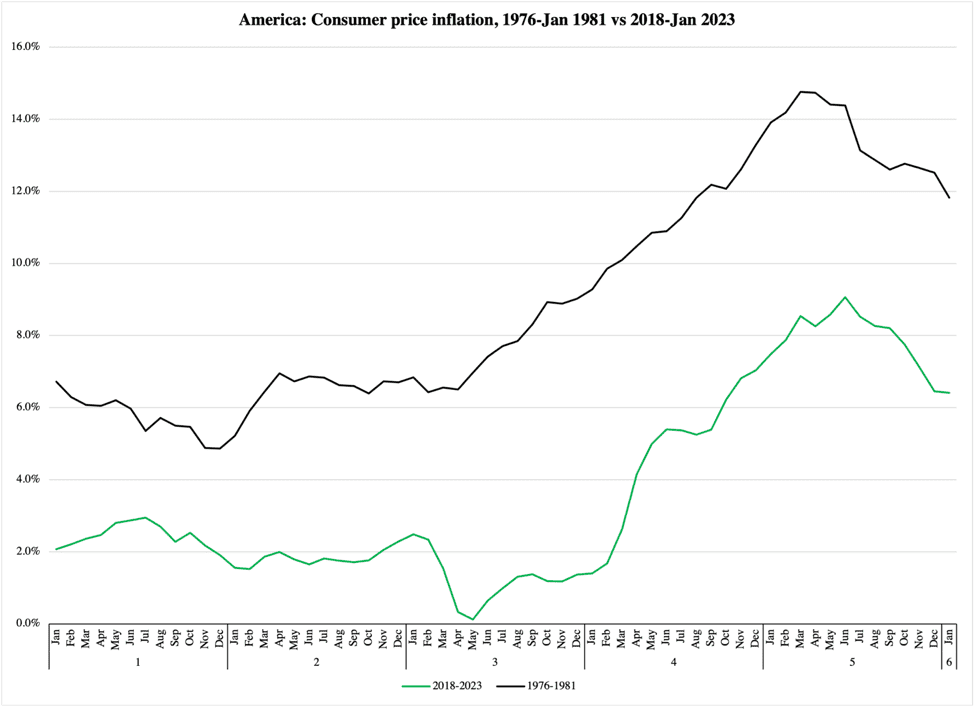

There is no doubt that the worry about stagflation motivated the Federal Reserve to abandon its excessively expansionary, pandemic-related monetary policy. The shift, which took place in late 2021, did not come a day too late. There is no doubt that America was on a path to stagflation. Figure 1 compares the trend in the broadest consumer price index for the U.S. economy from 1976 to January 1981, and from 2018 to January this year. (The years are numbered from 1 and up, applicable to both time periods.)

The similarity is frightening:

Figure 1

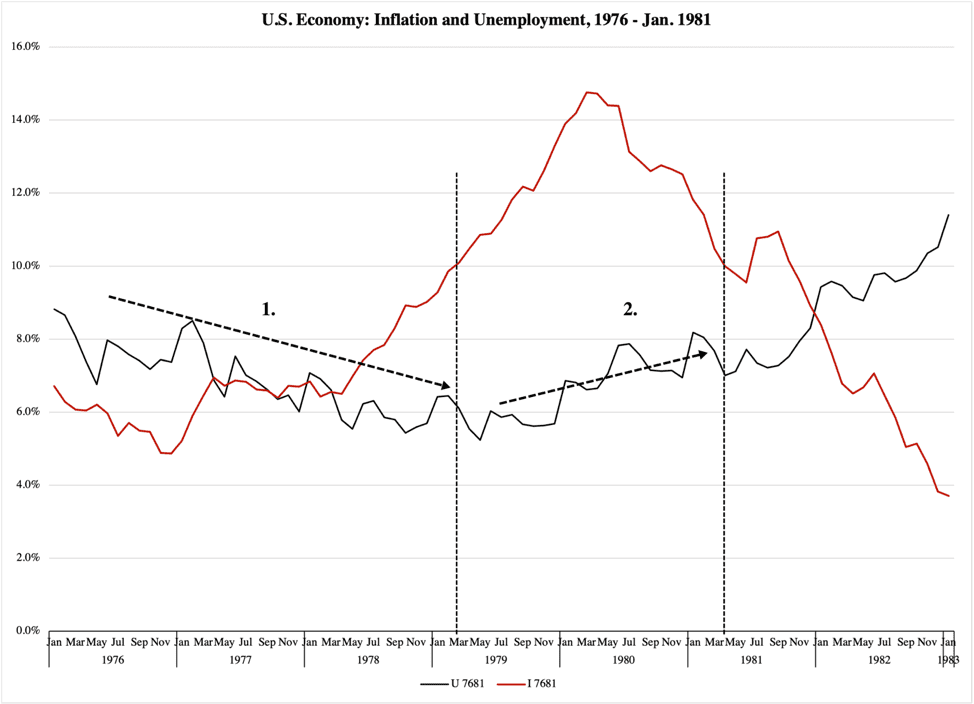

For stagflation to happen, the high rates of inflation must be accompanied by high unemployment rates. As Figure 2 shows, this did happen in the late 1970s. Inflation was already elevated as the U.S. economy fell into stagflation (the red function), but the rates were stable enough to make inflation somewhat predictable. This kept the economy going, which—as arrow 1 indicates—slowly drove unemployment down:

Figure 2

In mid-1978, inflation began rising at a rapid pace. When it passed 10% in early 1979, unemployment turned upward again (arrow 2). Even though the rise in unemployment was relatively slow, the upward trend continued.

For two years, inflation remained above 10%. Technically, not all of this period counts as the stagflation episode—the strict definition would put an end to stagflation in mid-1980 when the inflation rate turned downward again. However, a more practical definition suggests that any period of time where inflation is above 10% and unemployment is rising would qualify as a stagflation experience. This is the case at least for economies where double-digit inflation is a historical anomaly.

Once the U.S. inflation fell below 10%, unemployment kept rising for about two years until, in the summer of 1983, the recession turned into a recovery. Part of the reason was the sharp decline in inflation; had prices continued to go up at high rates, that recession could have turned into something very bad.

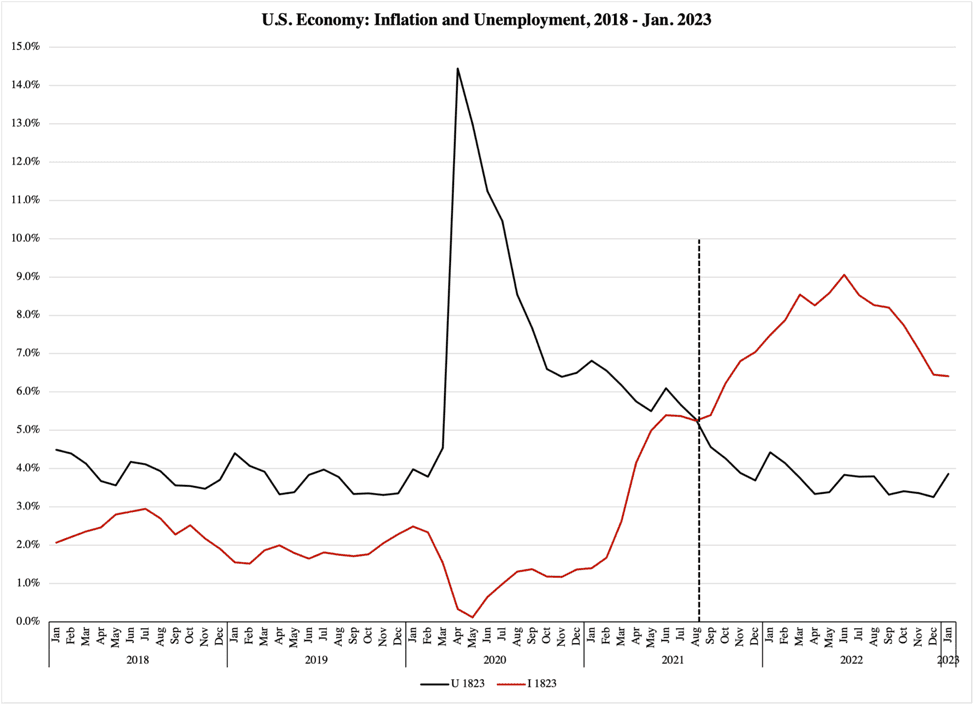

Fast forward to the 2020s. Figure 3 compares the same two variables as in Figure 2, but for the period from 2018 to January this year. The period starts with remarkable price stability and low unemployment, which continues all the way to the beginning of the artificial economic shutdown in early 2020. At that point, these two variables start behaving in precisely the opposite way than what would be characteristic of stagflation:

Figure 3

When unemployment skyrockets in early 2020, inflation falls sharply from already low levels. As the economy opens up again, inflation comes back in a gentle canter.

Then, in early 2021, things turn more dramatic. Inflation quickly accelerates, jumping above 5% in short order. By August of that year, the economy reached a point where stagflation became a threat: while inflation was still a far cry away from 10%, it started accelerating in a way that had no merit in the real economy. Meanwhile, unemployment continued to decline, but the pace slowed down quite a bit.

This was the turning point where the U.S. economy could have sunk into stagflation. That did not happen, likely because inflation never reached the same levels as in 1979-1980. When prices rise faster than a certain level, say 10%, it becomes increasingly difficult for businesses to plan their activities. Returns on investments in productive capacity become uncertain, as do payroll costs: the faster prices increase, the more workers will demand inflation-compensating wage hikes.

At its top in June 2022, U.S. consumer price inflation reached 9.06%. If it had continued upward, or just gotten stuck at that level, it is almost a certainty that unemployment would have begun rising, and rapidly so, no later than the fourth quarter of last year. Instead, inflation tapered off and unemployment remained stable.

The reason why America avoided stagflation is simple: the shift in monetary policy from expansionary to contractionary. In late 2021, the Federal Reserve reversed its pandemic-related—and highly irresponsible—printing of money. In an effort to curb inflation, it embarked on a slow but firm path to raise interest rates and bring down inflation.

As new research shows, it worked. In a new scholarly paper (pending publication with the American Business Review), Robert Gmeiner, economics professor at Methodist University in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and I explain the relationship between monetary policy, fiscal policy, and inflation. We outline the theory of how a monetary expansion for the purposes of paying for budget deficits inevitably causes inflation. We lay out the pathway for money to move from the central bank into the government budget—with the central bank buying government securities—and then out into the economy.

The last step happens primarily when government spends its borrowed money on benefits to the general public. I have previously written about this chain link here; in Gmeiner’s and my paper, we expand on the economics literature and show how economists, while having been worried about the money-to-inflation link for decades, have largely neglected the role that fiscal policy plays in that chain. This is why economists have failed to explain the precise cause of monetary inflation—and therefore the cause of stagflation.

After we fill this theoretical gap, we provide solid empirical results, demonstrating with near-perfect statistical evidence that the most recent inflationary episode was caused by the extreme monetary expansion in 2020 and 2021. We also show why there was no similar inflationary episode in the Great Recession of 2009-2011, further isolating fiscal policy as the transmission mechanism, or the conduit, for the monetary expansion to become inflation.

Our results, which add significant value to the body of economics research on money, inflation, and fiscal policy, will hopefully help policymakers avoid the decisions that otherwise can lead them down the path to destructive stagflation. There are, primarily, three steps that governments can take:

1. Avoid debt-cost shocks. Shift existing debt from short-term securities into long-term ones. This is particularly important for countries outside of the euro zone, as their currencies are more at risk in a recession when there is a higher level of stress on the sovereign debt markets. By restructuring debt toward securities with a life of several years, the treasury will not only shield itself from interest-rate shocks but also signal a long-term focus in its fiscal policy. This reinforces confidence among investors.

2. Structural spending reforms. Most budget deficits in modern welfare-state economies, including the European ones, are caused by government spending being structurally—in other words permanently—higher than tax revenue. The reason for this is in the very configuration of most modern welfare states, where high taxes depress economic growth, and low economic growth increases spending. A good way to permanently reduce the fiscal stress that a welfare state inflicts on an economy is to implement conservative reforms that rewrite the purpose of government. As Hungary has demonstrated, this is not rocket science. Just a nice combination of conservative common sense and good economics.

3. Keep taxes predictable. If there is one thing that can make an economic recession worse, it is to start tampering with the predictability of taxes. Nothing upsets the economy more than a government making frequent changes to taxes on personal income, corporate revenue, consumer spending, savings and wealth, and property. All too often, governments that are faced with big budget deficits resort to quick-fix tax hikes. This will only aggravate the loss of confidence throughout the economy.

Central banks that exercise monetary conservatism will help stamp out inflation from their economies. Governments who follow the three simple rules listed here will reinforce the anti-inflationary effects of monetary conservatism. The resulting decline in inflation will help the economy recover sooner than it otherwise would.

Most of all, this policy combination will help the economy avoid stagflation.