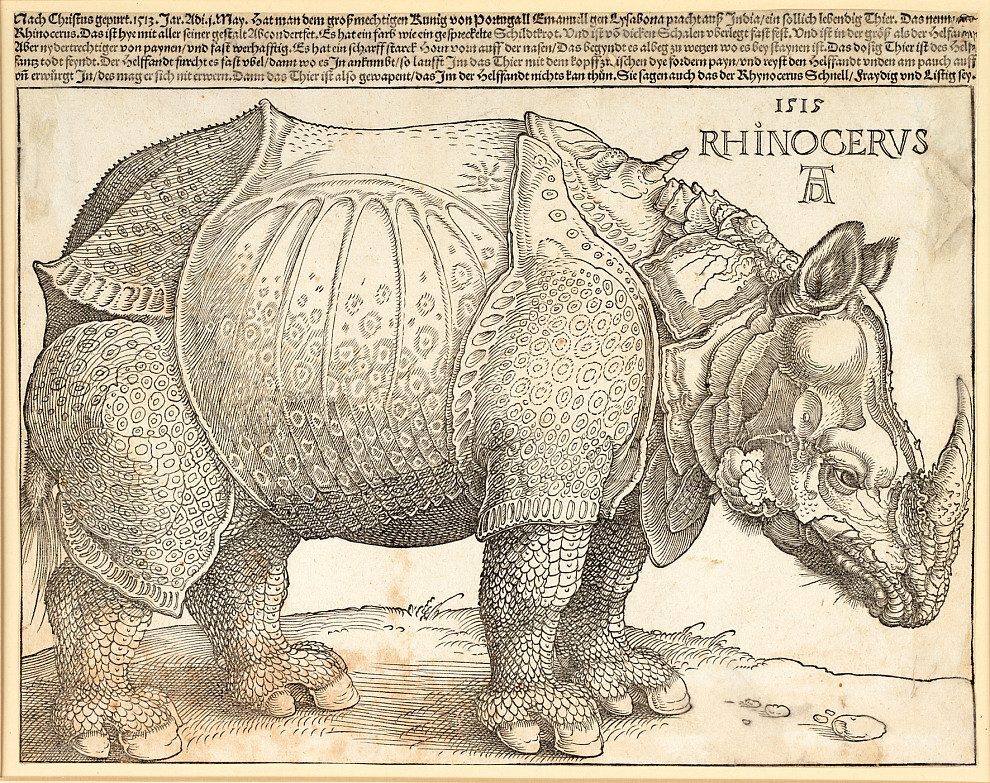

“Rhinocervs” (1515), a 21 × 30 cm woodcut and type printing by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), located in the Albertina, Vienna.

“Dürer, Munch, Miró” was the Albertina’s largest print exhibition to date with 169 works on display. It spanned six centuries of printmaking, from the late Middle Ages to the mid-20th century. Rivaling the British Museum and the Met, Vienna’s Albertina houses the third-largest collection in the world with 950,000 pieces in its permanent collection.

“Dürer, Munch, Miró” explored the birth and growth of European printmaking, from the myriad techniques of the late Middle Ages to the explosion of color in the 20th century. In the words of Director Klaus Albrecht Schröder, the scope of printing lends itself to a manifold increase in both artistic technique and availability. The exhibition was chronologically ordered, beginning with woodcuts and copper engravings from the 15th century. The diversity and detail that various printmaking techniques made possible is striking.

The rise of European art printing techniques coincided with the birth of book printing in the mid-1400s. This printing revolution made artwork widely available. Prints from throughout the centuries illustrate the growth and development of an artistic tradition. From the Old Masters, including Albrecht Dürer, Peter Bruegel, and Rembrandt, the art of printmaking yields a mastery of genre which leads up to the impressive modern and contemporary works including those of Toulouse Lautrec, Edvard Munch, Käthe Kollwitz, the Blauer Reiter, Oskar Kokoschka, Georg Grosz, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, and others in the 20th century.

Printmaking gave rise to enormous thematic diversity in a departure from the more constrained subjects of Renaissance painting, where a new humanism took center stage. Portraits, landscapes, sacral themes, and socially critical images all contributed to the richness of the new genre. Printmaking also allowed for the expansion of the space of shared art; prints could be transported all throughout continental Europe in a way that oil paintings could not. Prints took on a pan-European dimension precisely because they were serialized and could thus be bought or shown in many cities simultaneously.

The exhibit showcased many extraordinary artists, each of whom uniquely contributed to the development of printmaking. For example, the Albertina is home to the largest collection of Dürer prints in the world, from the Praying Hands, self-portraits, and The Hare. Dürer’s Rhinoceros of 1515, in particular, highlights the detail that characterizes his immense portfolio of prints. Perhaps one of his most famous prints, he was inspired by a rhinoceros that belonged to King Manuel I of Portugal. It was eventually given as a gift to the pope, but unfortunately the animal drowned on the way.

Rembrandt’s self-portrait of 1639 is testimony to his genius of etching. He captures the imagination with his remarkable attention to detail, even though the print is only black and white. The drypoint needle work required to create the self-portrait are indicative of his immense skill.

Francisco Goya’s Elephant and a dreamlike series of Caprichos were also on display, as well as works from the Disasters of War, a series of 82 prints which he made between 1810-20. Edvard Munch’s Madonna introduced color to printmaking, ushering in thematic changes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One of Toulouse Lautrec’s posters from his Montmartre series kindles the splendor of urbanism and the new pleasures of the bourgeoisie. Joan Miró’s work illustrates abstract and nonobjective printmaking.

Printmaking in Europe reflects a continuum and expansion of cultural dialogue and exchange heralding back to the late Middle Ages and pressing forward to contemporary works like those of Georg Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Emil Nolde, and Blauer Reiter. The developments in printmaking subjects and techniques up to the present day illustrate the wealth which an art form engenders. Albertina’s Director Schröder is convinced that prints are as valuable to the viewer as paintings.

The exhibition did full justice to the introduction of new color techniques at the turn of the century and into the mid-20th century. Six centuries of printmaking offered visitors a visual display of the genre in all of its splendor. Christof Metzger, the curator, created an exemplary exhibition.