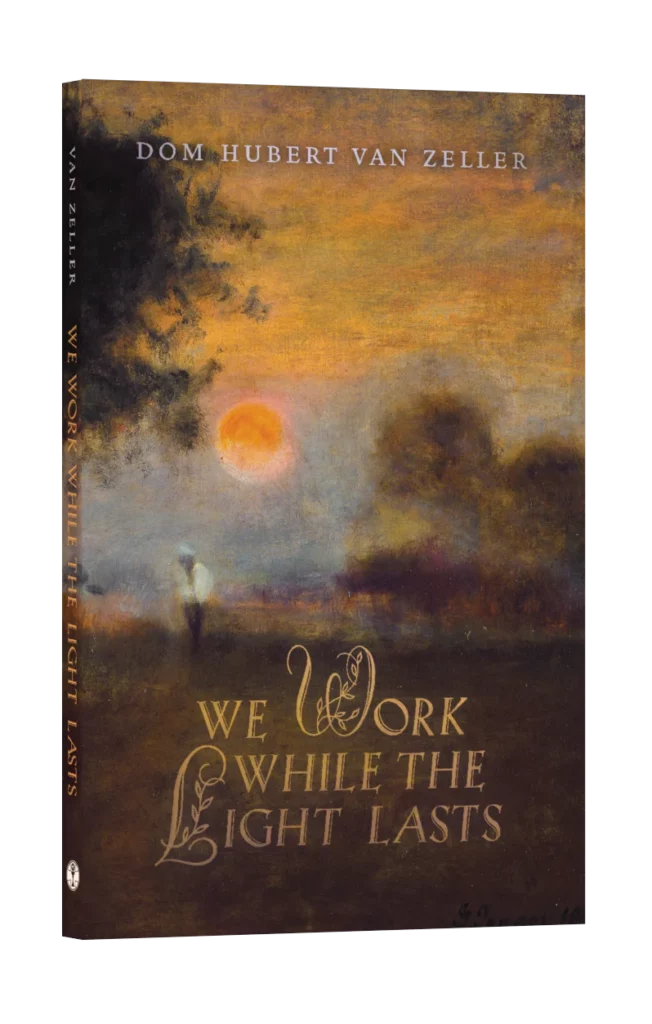

“The Evening Prayer” (1857), a 46.5 x 38.5 cm oil on canvas by Pierre Edouard Frère (1819-1886), located in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Groundedness in life’s joys and sorrows gives weight to spiritual advice unlike anything else. Writing from his and others’ experience of dryness and difficulty, the English Benedictine Hubert van Zeller challenges, engages, and motivates as few other spiritual writers can. Born in Egypt in 1905, van Zeller was educated at Downside Abbey in England, where he eventually entered as a monk. Many of his books, including his autobiography One Foot Out of the Cradle, convey the depth of his personality and outlook on life. Often ill-at-ease in the English Benedictine Congregation because of its emphasis on active apostolate in schools and parishes rather than enclosed monastic life, he received permission to spend much of his time giving retreats, writing, and pursuing art. The strong melancholic and pessimist streaks in his personality, combined with his sensitivity to beauty and human suffering, often lead to a refreshingly realistic view of life’s joys, sorrows, and meaning.

Van Zeller’s short book We Work While the Light Lasts is largely based on his correspondence as a spiritual director, and his experience that “the problem which men and women living in the world most want to discuss is that of how to handle the affections.” In forty-two short meditations on an extremely wide range of topics, van Zeller presents the universal call to holiness by bluntly addressing common tendencies in man. His writing has a British 1950s charm about it, yet cuts to what is essential in a way that feels modern and relevant.

The wide ranging subject matter makes it difficult to review the book’s general themes; however, a few of his most helpful attitudes and approaches can be pinpointed. First, van Zeller invites the reader to abolish any dichotomies between holiness and happiness. They go together; they are part of a unity, which is life. Similarly, work need not be separate from life, happiness, or holiness. They need not be things we add to our life or pursue separately; rather, we can and should find God and happiness in our work, which van Zeller essentially views as the obligations of our state in life.

Second, in his discussion of marriage, he emphasizes the differences inherent in the way men and women approach each other, how selflessness is the basis of such a relationship working, and the necessity of acknowledging the fact that sacramental marriage is built upon human love but cannot succeed unless it transcends it.

Finally, van Zeller insists on the necessity and possibility of a high level of prayer in the life of every Christian. This is both helpful and challenging. His advice always brings the reader back—through common objections and hangups—to the principle that the fundamental attitude of prayer is about God and not about self, and the fact that it is never useless to be in the right relationship with God.

Consider a few examples of van Zeller’s pithy style. In the first few pages on work and entertainment, he comments:

We have constantly to be reminding ourselves that our happiness does not come through our entertainment but that our entertainment, if it is to be what God means it to be in our lives, comes through our happiness.

He says of marriage:

Indeed it is difficult to see how the problem of two people permanently living together can be perfectly solved—any more than the problem of the spiritual life can be perfectly solved. When people say to you (and they are always saying it): “I would give anything to get my marriage right,” ask them if they would give themselves.

About repentance:

With all our faults, with all our worthless past and probable future lapses, with our black record of ingratitude and our somewhat hazy hope of self-reform, we are infinitely more pleasing to God at His feet than at a distance with our backs turned.

In the section on simplicity in prayer, we find this gem:

Prayer of the heart and mind, then, is intended to be a loving gaze at God and not a businesslike sorting out of self. So far as self-understanding goes, the ordinary working knowledge which most of us have already is quite enough; if we try to acquire any more of it we shall end up by gazing at self and not at God.

I recently recommended this book to a friend. A few weeks later, she spent a good hour on the phone telling me how much this book had inspired her to rethink her approach to prayer, selfishness, and the search for fulfillment and happiness in relaxation and work. We also agreed about how easily the short chapters read, how van Zeller’s hard punches on pride and complacency were strangely pleasant (like a painful massage), and our expectation of returning to it periodically for new challenges. If you are looking for a supernatural booster shot, a spiritual book to read for five minutes before bed, or a fresh way of approaching work, prayer, and the affections, look no farther than We Work While the Light Lasts.