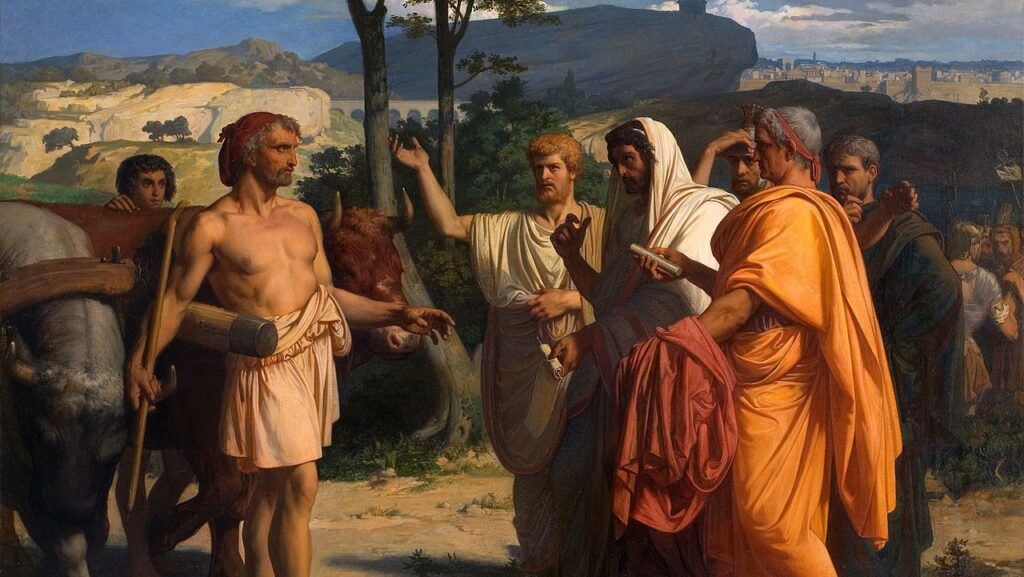

Cincinnatus Receiving Deputies of the Senate (1843), a 114 cm x 146.5 cm oil on canvas by Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), located at the Musée Fabre, Montpellier

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

The conservative movement is changing. Across the West, there is growing critique of the liberal-conservative fusion, in which conservatism emptied itself of content and largely forfeited its foundations. It allowed itself to be colonised by liberalism or outright libertarianism. Many conservatives adopted liberal notions of freedom and society and, under influence of neoliberalism, turned conservatism into an ideology that elevates economic efficiency and globalisation above all else. They became promoters of unfettered markets and extreme individualism, reducing man to a primitive homo economicus, society to a mere parallel to market operations, and culture and morality to purely personal choice and interest.

Conservatives thus abandoned public space as such. Social, cultural, and value issues, as well as virtually all institutions, were left to the liberal Left, even though concern for society and institutions has always been a central interest of conservatism. Too many conservatives accepted the parameters for discussion that were set by progressives, and even when they won elections, they played on a field staked out by the Left. In a spiral of caving in liberalism, many conservatives have failed to notice that conservatism has ceased to be a relevant social force, that it does not uphold conservative values or promote conservative policies.

A revival of the true core of conservatism must begin with the recognition that the West is under the absolute dominion of the liberal order. This order is based on the right-left liberal political consensus, whose central commitment is the liberation of the individual. The liberal consensus is economically neoliberal and socially left-liberal. Its central theme is economic and cultural deregulation, coupled with a commitment to transnational integration and global governance solutions. It is a fusion of neoliberalism and progressivism, promoted on a global scale. Its ideological expression: I can buy whatever I want, and I have a human right to whatever I want.

Neoliberalism refers to total preference for capital over the state and a maximum emphasis on efficiency. It is an economic model that results in the total domination of transnational capital and a weak position of states and labour. It calls for the removal of as many barriers to free movement of capital, labour, and goods as possible, and not only on part of the state: traditions, culture, local specificities, social considerations, or national borders can also become undesirable obstacles to the free market. This leads to the constant pressure for efficiency, flexibility, deregulation, liberalisation, privatisation of public services, reduction of labour protection for workers, and immigration.

Neoliberalism has led to the dominance of the financial sector over the real economy, the overall marketization and atomization of society, the concentration of economic power in a few monopolies, underfunded states with large debts, the transfer of wealth to the richest at expense of broad middle classes, and an increase in inequality. It is symbolised by technology giants such as Google and Amazon, which are more powerful than many governments and pay almost no taxes.

The left side of the consensus invokes diversity, equality, social justice. and relativizing tolerance. It promotes multiculturalism and mass immigration, an obsession with minorities and identity politics, anti-discrimination crusades, gender mainstreaming and transgenderism, political correctness and the fight against hate speech, indoctrination in education, and the inflation of human rights. Its aim is to demolish traditional norms and shared identities in the name of human liberation, and to free people from the ‘binding’ shackles of gender roles, family, society, nation, and Western culture.

It is of the utmost importance to realise that both sides of the consensus—neoliberalism and progressivism—work in synergy. Immigration, for example, is a human right and should be encouraged from a progressivist point of view, while from a neoliberal point of view it is a welcome source of cheap labour and a way of depressing wages. Similarly, global corporations are a product of neoliberalism, and their power over the global economic system is enormous; but at the same time they are the biggest supporters of progressive agenda, which suits the left side of the consensus perfectly. Those who want to reverse the dominance of the liberal consensus must define themselves against both parts of it.

The liberal consensus pretends to be a compromise between the Right and the Left. In reality, this progressive neoliberalism is a doctrine of the Western establishment, and it goes to extremes in both directions, in the sense that it is supported only by a tiny minority. Its policies, such as the weakening of the state and the privatisation of public services, or mass immigration and the relativisation of traditional identities, are extremely unpopular. This opens up an unprecedented rift between elite and people. Western elites are unwilling to embrace an agenda that reflects the interests of majority; on the contrary, they are quite deliberately plunging large sections of the Western population into economic and cultural insecurity.

The detachment of liberal elites from the majority is manifested in their growing distrust of democracy. Thus, a characteristic feature of liberal order is the hollowing out of democratic politics, however loudly liberals champion democracy rhetorically. They surround it with a web of undemocratic institutions and undermine the state’s ability to enforce the democratic will.

Typically, this involves transfer of competences to international organisations and commissions of unelected experts and officials, acceptance of commitments through international treaties, the increasing role of courts and judicial activism, the strengthening of large consultancies, multinational corporations or NGOs, and the privatisation of strategic sectors and public services. Liberalism is thus increasingly coming into conflict with democracy and thus with its only functional vehicle in the form of nation-state.

The central ethos of liberal consensus is liberation: the removal of boundaries and the expansion possibilities. This is reflected in both neoliberal economics and cultural deregulation. We are always looking for limits that can be overcome, whether it is national borders, economy and trade barriers, traditional gender identities, traditional understandings of normality or common decency, and so forth. This trend is supported by the media, the educational institutions, the entertainment industry, and big business.

Liberalism implies a total preference for the individual over society. As such, it licenses the unbridled pursuit of unlimited freedom, elevating personal selfishness to a defining social principle. It produces an atomised, narcissistic, and irresponsible individual, pursuing only his own gratification at the expense of his natural ties to his society, his culture, and the roles associated with it. In the name of extreme individualism and unlimited personal freedom, liberalism undermines the social cohesion and loyalty that the West has long cultivated. The liberal order is liquidating society.

Moreover, a society that is merely a sum of irresponsible individuals must be governed and regulated by an ever-increasing number of regulations. The result of liberal liberation is an individual thrown between the mill wheels of the market and the educational pressure of the state. An even greater paradox is that, despite a general atmosphere of liberation, concrete and tangible forms of freedom—freedom of speech, thought, property, and privacy—on which Western societies have long stood are in decline.

The West is technologically advanced and prosperous, but uninspiring as a civilization. It lacks a common ethos, a conviction of its own mission, and appreciation for its own culture. It undermines loyalty to civilisation and to the historical identities that are the basis of solidarity. It sees only the historical mistakes and not the beauty and wisdom that our civilization has accumulated. Liberalism has led the West into a crisis of values, culture, and identity.

A conservative revolution is needed to reverse this development. Its aim is to change the prevailing liberal narrative and revive the Western civilizational heritage. If the conservative movement is to have any meaning, it must offer an alternative to the entire liberal order. Against the endless liberation of the individual and the atomization of society, conservatives must uphold a concept of man as part of society with a shared identity and a shared ethos. This creates a sense of elemental trust and solidarity, which are the foundation of any healthy society.

The conservative vision of society accommodates the natural human need to belong somewhere. It affirms the natural human attachment to the near and familiar, to specific people and places, to one’s own nation, culture, and civilization. It embodies the constant search for a balance between freedom and order, between individual and society. It demands society’s respect for the individual, but also the individual’s loyalty to the society of which he is a part.

Conservatism offers a balance of rights and responsibilities. Therefore, it emphasizes concrete, tangible, and settled manifestations of freedom, such as private property, freedom of speech, or individual and family autonomy, but also its natural limitations, such as personal responsibility, patriotism, solidarity, authority, decency, and the ability to recognize certain limits. Society is not only about freedom, but also about loyalty and solidarity. And freedom is not only about choice, but also about quality of choice.

Only as an economic, social, and cultural alternative can conservatives become the voice of the silent majority who do not feel represented in elite levels of society. This majority raises children, works, creates wealth, pays taxes, is naturally patriotic, believes in proven institutions such as family, democracy, the nation state, and believes in a balance of rights and responsibilities to self, family, and society. The commitments of this majority must be the central concern of conservatism, and conservatives must represent its economic and cultural interests.

On a political level, this requires conservatives to define themselves not only to the Left against liberal progressivism, but also to the Right against neoliberalism and libertarianism. They must not only oppose social engineering and left-wing utopias, which, in new and old guises, are once again threatening the free societies of the West. It is equally crucial that they free themselves from blindly following the neoliberal mainstream, which claims that there is no alternative, while at the same time destroying the Western middle class and deepening systemic inequalities.

The clash with progressivism demands a willingness to engage in the culture wars. Culture wars are often ridiculed and ignored on the Right, on the grounds that they have no real impact and that real issues like taxes or budget need to be front and center. These are undoubtedly important issues, but conservatism was founded on the idea of preserving society and its culture, and earlier generations of conservatives were very aware of this. Both economy and culture need to be addressed. Conservatives who do not understand the fundamental importance of the culture wars are useless.

The culture wars are a struggle for the essence of the West. In sum, conservatism requires the affirmation of the traditional culture and moral order of the West. In contrast, progressivism portrays Western societies as structurally unjust, discriminatory, and racist. It implies a struggle against the majority and its culture, identity, values, and morality. Conservatives must begin to displace the liberal progressivism that now dominates the free societies of the West.

The role of institutions is key here. The culture wars will ultimately be won by those who control the intellectual, educational, cultural, and economic institutions of the West. These are currently in the hands of liberals. This is why conservatism is not a relevant social trend today and why society is in many ways changing beyond recognition before our eyes, regardless of the true sentiments of the silent majority. Conservatives are losing the culture wars. The return of conservatism to institutions after years of marginalisation will be difficult and lengthy, but it is necessary.

For conservatives, the fastest way to influence is through democratic politics. This is the only sphere where conservatives can make a relatively quick impact and be a counterweight to mainstream liberal media, culture, academia, and big business. Thus, the first institution that conservatives have at their fingertips is the much-reviled state. They must not be bound by outmoded ideological precepts, and must commit to wielding the executive, bureaucratic, and legislative powers of the state to combat progressivism.

In economic policy, it is necessary to reject free-market dogmatism and neoliberal mantras, such as deregulation and the privatisation of public services. Conservatives need to be more pragmatic, paternalistic, and non-ideological about the role of the state and the market. Their highest political consideration must be national interest, not the market.

National interest means strengthening the national economy, protecting strategic sectors, supporting families, and ensuring social peace. The goal of conservative politics is not to maximise individual choice and efficiency, but to promote solidarity, stability, security, and the ability of people to start families and have children. There is a balance to be struck between these objectives, but the market alone cannot strike it; only society, or the state, can. The state exists precisely because there are areas of life where efficiency cannot be the only criterion. It is therefore essential for conservatives to rethink their relationship with the state.

A conservative revolution, then, will depend upon the return of political conservatism, such as Disraeli’s ‘one-nation conservatism,’ Gaullism, or German Christian democracy, which have all been forgotten under the weight of neoliberalism. These movements combined a belief in traditional values and institutions with a vision of economy and social policy that benefits ordinary people—the majority. According to this vision, society ought to be organised around the reconciliation of class interests.

The conservative revolution is a revolt against liberalism on many levels, and a return to more traditional forms of conservatism. It is not, however, a call for a return to the past; rather, unlike proponents of outmoded liberal-conservative fusion stuck in the world of Reagan and Thatcher, it reflects the current state of society and responds to contemporary problems. Conservatives have a choice: they can be staffage to a declining liberal order, cocooning themselves in intellectual snobbery while preaching ‘civility’ and ‘moderation,’ and earning praise from liberals now and then; or they can fight back and start defending conservative positions and advancing a conservative vision once again.

The task of conservatives was accurately stated by Benjamin Disraeli, who said that “we must be conservative to preserve what is good and radical to uproot what is bad.” Conservatives since the 1960s have too often failed at the former, because they have thought only of taxes. They then completely forgot about the latter, because, under the influence of liberalism, they came to believe that good and evil do not exist, that everything is relative, and that it is possible to be neutral. We are acutely experiencing consequences of both these failures across the West. It is high time to return to Disraeli’s slogan—a change that many conservatives find truly revolutionary.