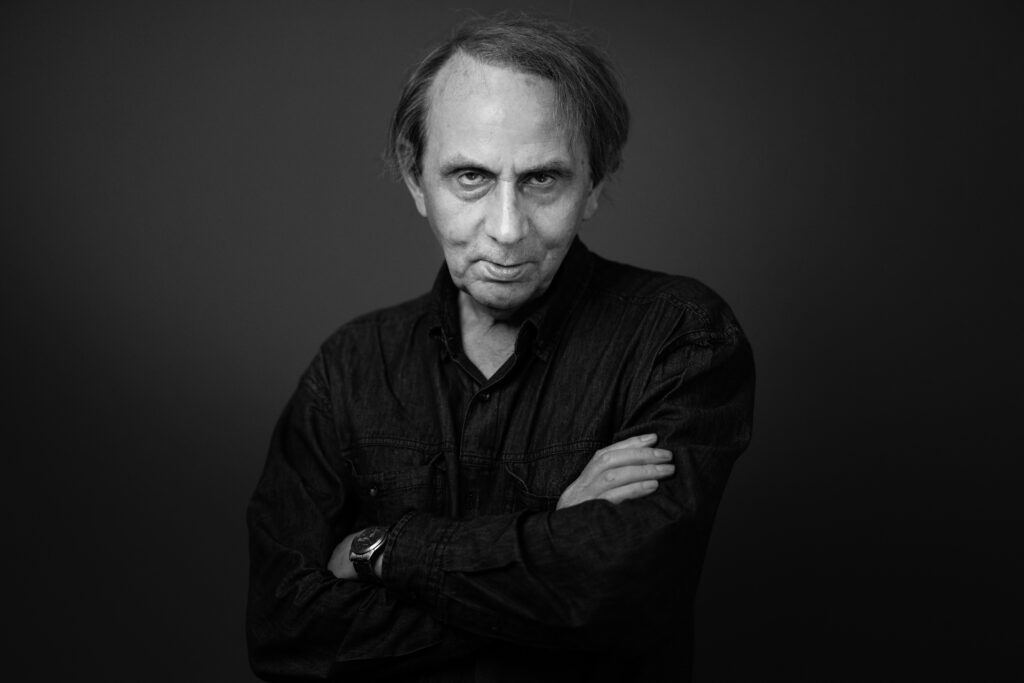

Michel Houellebecq in Paris on June 30, 2023.

Photo by JOEL SAGET / AFP

It was not easy to meet with Michel Houellebecq. After a quick initial acceptance, the process of scheduling an appointment dragged on. He had retreated after the uproar surrounding his allegedly Islamophobic statements in a conversation with Michel Onfray and the scandal that erupted after he was filmed having sexual intercourse with two young Dutch women for an artistic project. Both affairs weighed heavily on him, and he decided to wait for the publication of his diary Quelques mois dans ma vie (A Few Months in My Life) before opening up to the press again. When we finally met, we spent a solid five hours together on the terrace of Brasserie Le Coche. Michel Houellebecq was in the mood for conversation even after the exhausting double interview that Ute Cohen from the Tagespost had conducted with him and me.

Throughout the wave of recent scandals, Houellebecq, an enfant terrible of French literature, felt misunderstood by supporters and opponents alike. In Quelques mois, he has presented an apology in which the figure of art and the biographical self fall completely into one. It provides a breathless insight into his deep sensibility—but also shows that he had previously underestimated the extent of the culture war tearing the West apart.

In his discussion with Onfray, he took a strong position on mass Muslim migration to France. But when he faced threats of legal action and even murder, he retracted or reinterpreted many of his statements. In our interview, Houellebecq insisted that French criticism of mass migration was not rooted in concerns about seeing one’s own culture displaced by another, but only in the link between migration and crime. Moreover, he did not want to attribute the almost unmanageable problems of the suburbs (terrorism, honour killings, vandalism, looting, clan criminality) to Islam or the Sharia—which he regards as compatible, in principle, with republican legislation—but only to unfavourable social conditions.

It is true that he calls for an end to mass migration and regards Viktor Orbán’s migration policy as a good political example of how to accomplish that end. However, his unwillingness to acknowledge the conflict between the Muslim world and Western life or to take grand remplacement (great replacement) seriously has made Houellebecq—an icon of the Right since Soumission (Submission)—a persona non grata overnight.

Houellebecq also faced backlash from his involvement in what was originally a largely private film project. The backstory is complex, but it seems that the man of letters—who had regarded the film as a kind of final erotic memoir—felt betrayed and forced to litigate because of the uninspired nature of the encounters in question and the Dutch director’s refusal to respect Houellebecq’s disavowal of the film. The ensuing polemics and the topos, employed by both Left and Right, of the old white man degrading young girls to mere sex objects cost Michel Houellebecq his status as a classic.

This fall from grace was largely incomprehensible to him. He only began to understand it in the course of our conversation. Admittedly, he hit on one of the aspects of the problem when he commented, with a chuckle, that the feminists were not accusing him of being macho, but rather of being “old and not beautiful.” Since #metoo, the accusation of sexual exploitation is especially employed when there is an asymmetry of any kind between the two parties involved.

But that is not all. It seemed to me that Houellebecq is only now realizing that modern ‘wokeism’ goes considerably further than classical feminism, which merely criticized patriarchy and Philistinism. Progressives used to appreciate Houellebecq’s novels because he contributed to the deconstruction of the ‘outdated’ family and modern liberalism. Now that the aim is to reconcile Left-Green elites with big business and to promote gender fluidity, Houellebecq’s free but otherwise exceedingly classical view of sexuality and character seems increasingly outdated, even dangerous. It makes sense that he has been reinterpreted as a right-wing nostalgist for patriarchy.

Houellebecq now sits between two stools, since neither the Left nor the Right can comprehend his apparent change of course on the two key issues of modern identity politics, namely Islam and sexual identity. I use the word ‘apparent,’ because anyone who reads Houellebecq with an open mind knows that he would never allow himself to be completely taken over by a right-wing patriotic agenda for the West—whose disintegration he considers far too advanced for that—nor that he would ever want his sometimes thoroughly cynical hedonism to be understood as a social struggle against capitalism or patriarchy. Houellebecq has toned down his previously rather sharp views on Islam, and in the case of the porn movie, he has become the victim of a situation that he himself caused. On the whole, however, Houellebecq has remained the same in many respects, as is also shown by his crusade, deeply moral and as courageous as it seems outmoded, against every form of euthanasia, which he describes as his “last stand.” He is a dystopian visionary who has discovered that reality has overtaken him.

This essay appears in the Fall 2023 edition of The European Conservative, Number 28:54-55.