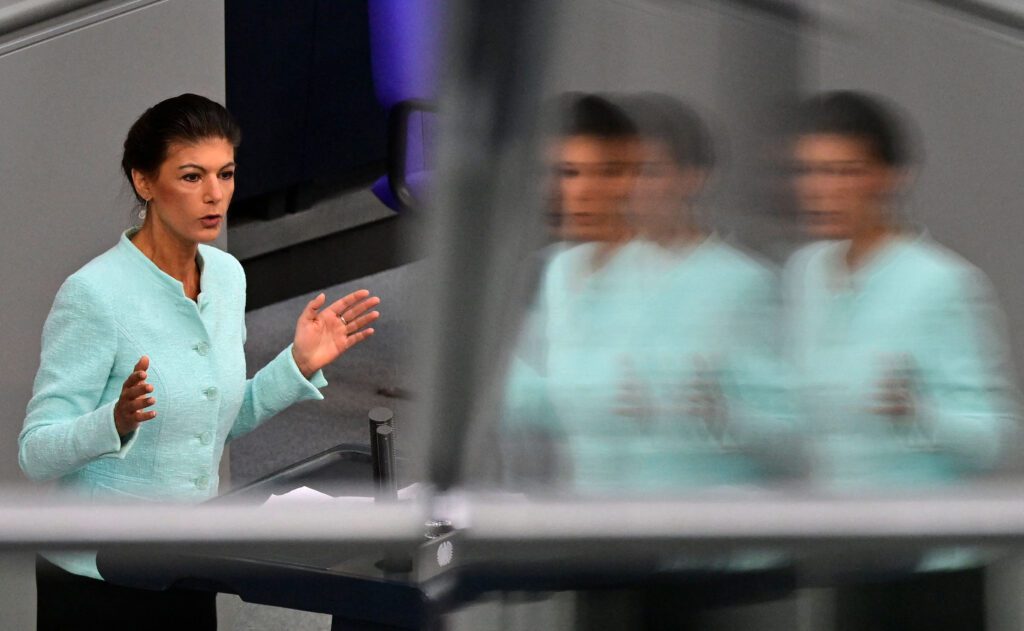

It looks like it’s curtains for Die Linke (The Left), the German hard-left party. Thirty-three years after German unification, The Left seems finally set to die. Erich Honecker’s heirs, as they were sometimes called, are at the end of the road. Following years of decline, the final nail in the coffin comes with the defection of Sarah Wagenknecht, a charismatic star of Die Linke and a highly controversial MP. Her departure marks the final chapter of the party.

For many months, The Left has been paralyzed by bitter infights. One of Wagenknecht’s prominent allies has publicly called the parliamentary group a bunch of “incapable political clowns.” Veteran MP Gregor Gysi laments a “climate of denunciations.” The party leadership has insisted for months that there is only a future without Sahra Wagenknecht.

Fierce infighting about the party’s stance on Russia and sanctions after the invasion of Ukraine has been a catalyst for the rift. Wagenknecht objects to the sanctions and blames the West for an alleged “economic war” against Russia. However, there has also been a longstanding and bitter dispute about the extent to which The Left should emulate the Greens and emphasize climate change and other supposedly progressive, fashionable topics like transgender rights; or, whether it should instead stand for the classic ‘social question’ issues like higher wages and the welfare state.

Wagenknecht, who was a hardcore Marxist and unapologetic Stalinist in the 1990s, has changed considerably since then. She despises the “lifestyle Left” and has called the Greens “the most dangerous party” in Germany. At age 54, her ideological model is a political hybrid: left on economic terms and right on immigration control. However, many of her allies are dubious hard-left fellows with pro-mass migration credentials.

This Monday, Wagenknecht will announce the launch of a new party. In preparation, her friends have founded an organization named Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance). More than a handful of MPs from Die Linke are now expected to leave the party.

Their defection will cost Die Linke its legal status as a faction in the German parliament, depriving The Left of millions of Euros in public subsidies and wage payments from the Bundestag. At the same time, Wagenknecht’s new party will probably steal enough votes from The Left to squeeze it below the legal threshold of 5% at the next election. This will mean the end of The Left’s national representation.

Old Comrades and Stasi Officers

From a conservative, patriotic point of view, the foreseeable death of The Left offers little cause for grief. Die Linke is the legal successor party of the Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands or SED) which, from 1949 to 1989, ruled the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), the communist dictatorship in the East. It was the party of Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker, responsible for the erection of the Berlin Wall and the internal border, where around a thousand people were shot or bled to death while trying to escape the GDR. The SED was responsible for the repression and surveillance of 17 million people in the East, with millions being spied on by the Stasi and several thousand detained in special Stasi prisons. The communists were responsible for profound misery, producing a broken country with many broken souls.

When the GDR collapsed in 1989, the SED hastened to rename itself as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) to shed its tainted reputation. The SED/PDS also managed to acquire much of the undisclosed fortune that the SED state party had stashed away. The historian Hubertus Knabe has presented evidence that the SED/PDS politician Gregor Gysi was responsible for concealing and stockpiling the SED fortune. It was Knabe who named The Left “Honecker’s heirs”.

The PDS became a new political home for legions of Stasi officers and thousands of old comrades, SED functionaries, and politicians—some with criminal convictions, such as Hans Modrow (the last communist premier of East Germany). In 1990, the party had more than 200,000 members. Many middle-ranking comrades used the PDS to start new political careers in Germany after reunification. Party leader Gregor Gysi had been a SED member since 1967 and was a privileged member of the East German socialist state as a barrister (and, one suspects, he betrayed some of the dissidents to the Stasi he was supposed to defend). It is alleged that his Stasi name code name was “IM Notar.”

Red-Red Coalitions

During the 1990s, most conservatives considered the PDS a taboo. The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) tried to warn the Social Democratic Party (SPD) against alliances with the ‘red socks.’ Nevertheless, step by step, the PDS, with its strongholds in the former GDR, gained acceptance in many left-leaning and liberal media as the party of East Germans.

In 1989-1990, when the rotten communist economy failed, the GDR collapsed. However, Chancellor Helmut Kohl raised expectations with his promise of “blühende Landschaften” (blooming landscapes). There was no blooming—or booming—in the beginning, but rather high unemployment and deindustrialization as the ruins of the socialist economy were dismantled. Understandably, many voters were profoundly dissatisfied, and a sizable number voted for the PDS. Ironically, those responsible for the dismal state of the broken East then became the advocates of the dispossessed and the apologists of Ostalgie (nostalgia for the GDR).

In the general election of 1990, the party gained 11% of the vote in five eastern states of Germany and East Berlin. It did not clear the 5% threshold, but nevertheless gained access to the Bundestag because of a special electoral rule for the East. In 1994, the PDS share almost doubled to 20%. Not long afterwards, the SPD broke the cooperation taboo when the PDS was allowed to enter a toleration agreement in Saxony-Anhalt to prop up a minority SPD government in 1994. In 1998, the first ‘red-red coalition’ was formed. From 2002 to 2011, the PDS/Linke was a junior government partner in Berlin. Thus, the once-divided city was governed by the heirs of the SED state party, which left a very bitter taste for victims of the communist repression system. From 2016 to 2023, The Left was again the junior partner of a coalition with the SPD and the Greens. The senator responsible for culture was then instrumental in a scheme to remove Hubertus Knabe from his position as head of the memorial site at Hohenschönhausen, a former Stasi prison.

The Left Is Running Out of Road

In 2007, the PDS merged with a West German left-wing startup, partly a breakaway group from the SPD, under its former party chairman, Oskar Lafontaine, Wagenknecht’s husband. The party adopted the name Die Linke. After its initial successes at the cost of the SPD, The Left has been in a slow-motion death spiral for many years now and is running out of road. Most recently, they lost their representation in the parliament of Hesse, their last stronghold in the West.

With the emergence of the right-wing protest party Alternative for Germany (AfD) after 2013, and especially in the wake of the 2015 migrant crisis, a large share of former Left voters in the East defected (especially after the 2015 migration crisis) to this new challenger which was calling for tighter controls against large-scale migration. In the general election of 2021, The Left only gained 4.9% of the national vote. It was only thanks to three directly-elected MPs that The Left could enter the Bundestag with 39 MPs. The departure of Wagenknecht and her allies deals a fatal blow to that faction.

From Tragedy to Farce

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx wrote that great historical facts and persona appear two times: “The first time as tragedy, the second time as mere farce.” The present German political circumstances offer some parallels. Young Sahra Wagenknecht was once likened to Rosa Luxemburg, and the tragedy of the far-left party will probably return in a short, farcical second life.

The launch of Wagenknecht’s party will have two consequences: it will destroy her former left-wing party and it will attract some protest votes from the AfD. This prospect has delighted left-liberal media. The Hamburg-based magazine Der Spiegel wrote, “Do it, Ms. Wagenknecht,” opining that her new party will “damage the AfD and benefit democracy.” However, it is far from certain that Wagenknecht’s new party will be a lasting success. In 2018, she tried to form the Aufstehen” (Rise) movement, which quickly faltered and disintegrated amid bitter infights, chaos, and controversies.

Wagenknecht is aware that her new party will attract a lot of “extremists and cranks,” as she has herself conceded. Wagenknecht has also admitted that she lacks organizational talent. She is a speaker, a writer, and an intellectual, not an organizer. Her first aim will be to get a good result in the election for the European Parliament in June 2024. After that, she will eye the three state elections in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg.

It is likely that the Wagenknecht party will grow, then implode. Her first and inevitable casualty will be Die Linke; its time is over. After the tragedy of communist rule in Germany comes the farce of rival, successor factions fighting tooth and nail to the death.

Even with the prospective death of the party of The Left in Germany, the Left in general remains very much alive. The governing Green Party and the SPD are rife with left-wingers, woke progressives, and ideologues. Self-declared left liberals hold intellectual dominance over the universities and the media. However, this hegemony is being challenged by a populist uprising in the form of the AfD. Some on the Left hope that Wagenknecht’s party substantially cuts AfD’s voter share, while others are more wary. A commentator in Süddeutsche Zeitung recently cautioned that it might be “the deception of the year” to expect that the launch of Wagenknecht’s party will do much harm to AfD, and a comment in Die Zeit warned that Germany’s democracy would become more polarized and unstable.

Most likely, Wagenknecht’s new party will be a brief episode while the real fight for the future course of Germany is fought on the Right.

In an earlier version of the text, Egon Krenz was incorrectly mentioned as a member of the Left. In fact, he was excluded from the party in 1990.