Here and elsewhere, I have argued that conservatives must adopt a robust attitude to

cultural preservation, creation, and advocacy. It is only by so doing that the long

heritage of Western tradition can endure, a tradition which has been entrusted to us by

the many generations that have gone before. That tradition is one for which our

ancestors invested—in their toilsome and all-too-brief lives—the great measure of their

time, their money, and even their blood. We must not forget the immensity of the debt

that we owe to the people of the past, who have provided us with countless evocations of

the greatest that humanity can achieve in art, making life not something to be endured

but to be enjoyed. That duty is always laid upon the present, especially when, as now, it

may seem that Western culture is languishing and struggling to carry on.

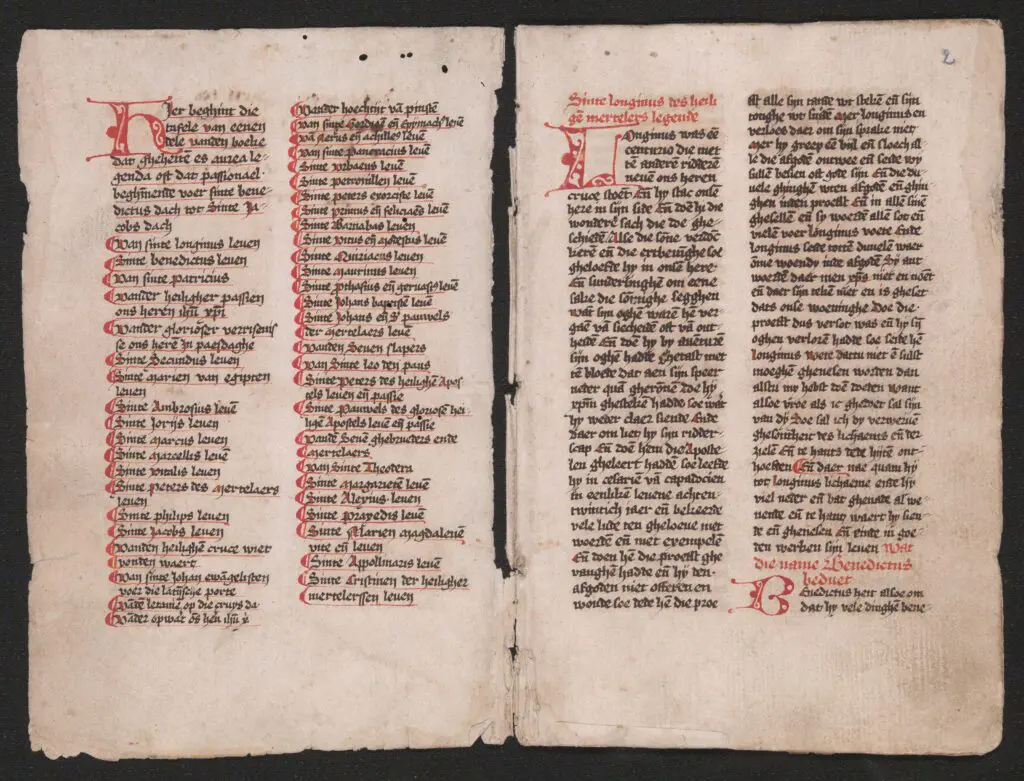

During the high Middle Ages, European culture was alive and vibrant, brimming with rediscoveries and new developments in the fields of art, architecture, music, literature, and philosophy. There were even bestsellers, of a sort: The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa at the end of the 13th century, went through an average of two new editions each year for the 50 years following its first publication in 1265. The text, which provided encyclopædia-like explanations of feast days and chronicles of saints’ lives, was so popular that the very title ‘golden legend’ became a commonplace term to refer to any remotely similar collection of hagiographies.

Although The Golden Legend was most likely intended for priests to use as a resource, it was soon being read in private homes. And, when a new manuscript was being created, the stories of local saints were often added in by enterprising scribes and printers. For example, when William Caxton published his English edition in 1483, he made certain to include English saints, such as King Edmund the Martyr, who were not present in the original edition of the mid-13th century. In this way, the text achieved enormous popularity aligned with a degree of personalised relevance. So extensive was its influence throughout the culture of the high Middle Ages that art history scholars still use it today in order to identify the depictions of saints found in paintings from the era.

But The Golden Legend was not loved simply because it was edifying; its stories were also interesting and even exciting—with tales of saints’ heads that continued to speak even after they were struck off, ravenous lions that refused to devour holy men and women, and other similarly miraculous happenings. Invariably, each story ended with the spiritual—if not temporal—triumph of the subject, thereby delighting Christian readers and bolstering them in their faith. On holy days, families might gather to read the entry for the saint of the day: to hear the etymology (usually deliberately far-fetched) of the saint’s name, to listen with awe or alarm at the saint’s demonstrations of holy virtue in the face of terrifying violence, and to be reassured of the saint’s spiritual ascent into Heaven, where even now intercession might be offered on behalf of those who were hearing the tale.

The popularity of The Golden Legend continues to endure. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow used the title for the second section of his Christus: A Mystery, which depicts the story of a young woman’s heroic virtue overcoming the wiles of Lucifer. When Sir Arthur Sullivan set Longfellow’s poem to music, it became his most famous ‘serious’ musical work, resulting in a performance by royal command for Queen Victoria, who sent for the composer after the concert to offer words of approbation and encouragement. In the 20th century, interest continued to build, leading not only to a modern recording of Sullivan’s distantly related cantata, but also to new editions of Voragine’s text, including William Granger Ryan’s two-volume English translation, the first edition to present the entirety of Voragine’s original text in English.

In many ways, The Golden Legend owes its continued popularity to its adaptability. From the earliest manuscripts, scribes and printers were emending the text, updating it with new, local audiences in mind. Likewise, Longfellow’s poem draws upon the overall purpose of Voragine’s text even as it abandons the structure and content; the seriousness of that material is what encouraged Sullivan’s own musical efforts. Even Ryan’s scholarly, modern English translation highlights the text’s enduring ability both to edify and delight: “offering an important guide for readers interested in medieval art and literature,” and also “bringing the saints to life as real people” who “do things that ordinary people can only wonder at.”

But The Golden Legend is not unique as a work that succeeds because of its adaptability. The Matter of Britain—tales of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table—continue to command immense cultural capital precisely because of their many adaptations, whether good, bad, or indifferent. Like John Dryden before them, Keira Knightly and Guy Ritchie may not have given to the tradition of Arthuriana anything that will last centuries, but their efforts have kept it in the cultural imagination, ensuring that the light still burns until more fit hands can make it blaze anew.

These efforts are, clearly, an important part of the enterprise of keeping valuable culture alive through the occasional doldrums that crop up now and again in the life of a cultural tradition. Both Dryden’s King Arthur and Longfellow’s The Golden Legend deviate from their source material so much as to be practically unrecognisable; but, at the same time, both also ensured that the light of those traditions was not extinguished. From the perspective of cultural conservatism, which ought prioritise the preservation of our most important and influential artistic achievements, Dryden and Longfellow carried on essential work. Modern artists should at least aspire to do likewise alongside their own novel creations.

In the early and mid-20th century, similar work was undertaken by authors and film directors with the great biblical epics: the 1896 novel Quo Vadis became a major 1951 film success; Cecil B. DeMille’s trilogy of The Ten Commandments (1923), The King of Kings (1927), and The Sign of the Cross (1932) were followed by the phenomenally successful epic The Ten Commandments (1956); the best-selling 1942 Lloyd C. Douglas novel The Robe became a box office winner in 1953; and Ben-Hur (1959), one of the highest-rated films ever made, was a remake of a 1925 film which had itself been adapted from an 1880 novel by Lew Wallace.

The stories told by these films were not outside of the public consciousness—quite the opposite. The criticisms levelled against The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) were that its moral instruction and stories were too familiar, being the sort of thing that almost every viewer had already encountered in Sunday school, and that it was delivered too ponderously. The success of such films came from adapting them from their customary modes of encounter—the Bible class, the church sermon, the family recitation from scripture—into new and exciting modes of experience such as the big budget epic film. The need to delight as well as to edify was as important then as it has been since Horace’s injunction in the Ars Poetica.

Today, there are still conservative artists who carry on the important work of keeping the great achievements of Western culture alive in the arts. Jane Clark Scharl’s verse drama, Sonnez les Matines, sees John Calvin, Ignatius of Loyola, and François Rabelais mixed up in a Paris Mardi Gras murder mystery. The formal quality of the work itself is an act of cultural preservation in a world where free verse rules the roost, to say nothing of the faithful representation of the philosophical attitudes of the three main characters. Yet the format is entirely amenable to modern audiences as well, given the popularity of crime podcasts and television programmes like Only Murders in the Building.

Christian priests, authors, composers, and artists of every stripe have kept the culture of the West alive for thousands of years, even as they have added to it and critiqued it themselves. In fact, the desire to preserve the great works of the culture is one of the fundamental principles of Western culture, such that a conservative attitude towards cultural preservation is not merely accidental, it is essential. For this reason, works like those of Scharl and others must be championed and patronised, and conservative culture should encourage their creation. In this way, we may both see out the temporary doldrums that all cultures experience, and also outlast the elements that would seek to undermine our cultural heritage in order to replace it with something not merely destructive, but inferior.