On December 4th, the European Central Bank reported that interest rates in the euro zone continued to rise in October. The cost of “new loans to corporations increased by 17 basis points to 5.26%.” This adds to the cost of doing business, which in turn compounds the problems for the European economy, which is slowly but steadily moving into a recession.

According to the ECB, interest rates on bank deposits also increased in October. This gives both households and corporations a little bit more return on the money they put in their savings accounts. However, from a macroeconomic viewpoint, the current trends in interest rates are not what Europe needs. When it pays more to save and costs more to borrow, less money will be spent and invested, which means current economic activity suffers.

Fortunately, there are indications that interest rates may be coming down in the next few months. The strongest indicator of this comes from the market for euro-denominated sovereign debt, where yields on treasury securities began falling in mid-October.

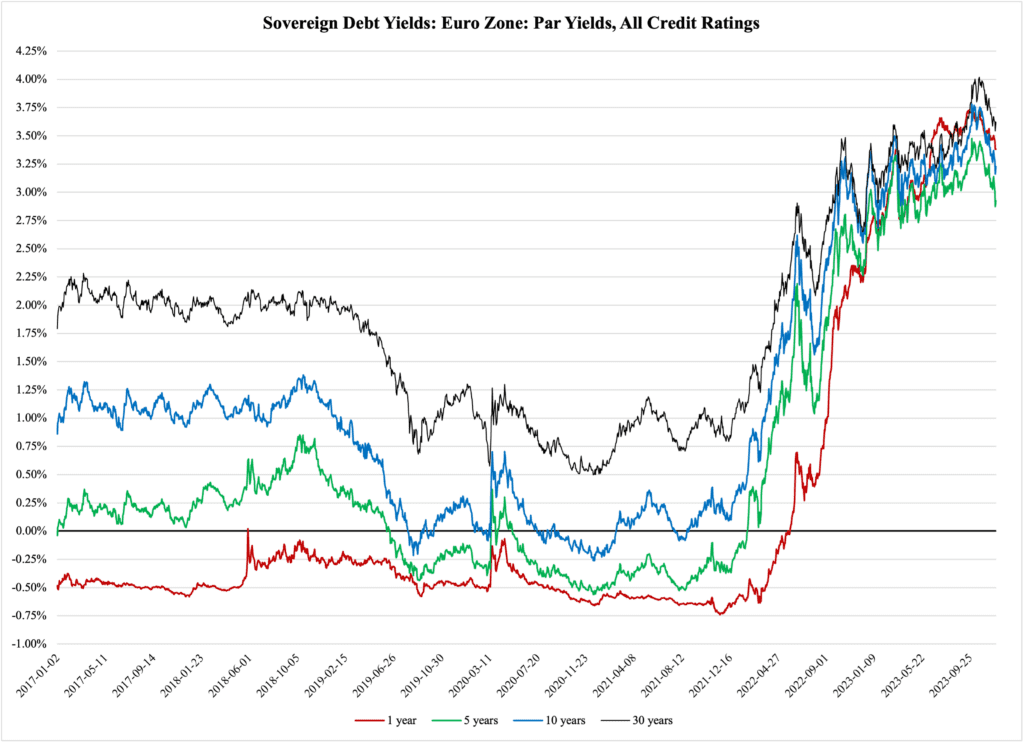

Before we look at just how much the yields have come down, let us take a step back and get a historical perspective on today’s interest rates. Figure 1 reports the par yields on euro-denominated sovereign debt (all credit ratings) with maturities of 1, 5, 10, and 30 years, since 2017. Through 2021, rates were either positive but below 2%, or actually negative; when the ECB reversed its monetary expansion starting in early 2022, yields shot up fast:

Figure 1

This background is important: it puts the recent trend of declining yields in perspective. For many years, both Europeans and Americans got used to cheap credit. Their governments got used to virtually, even literally cost-free borrowing.

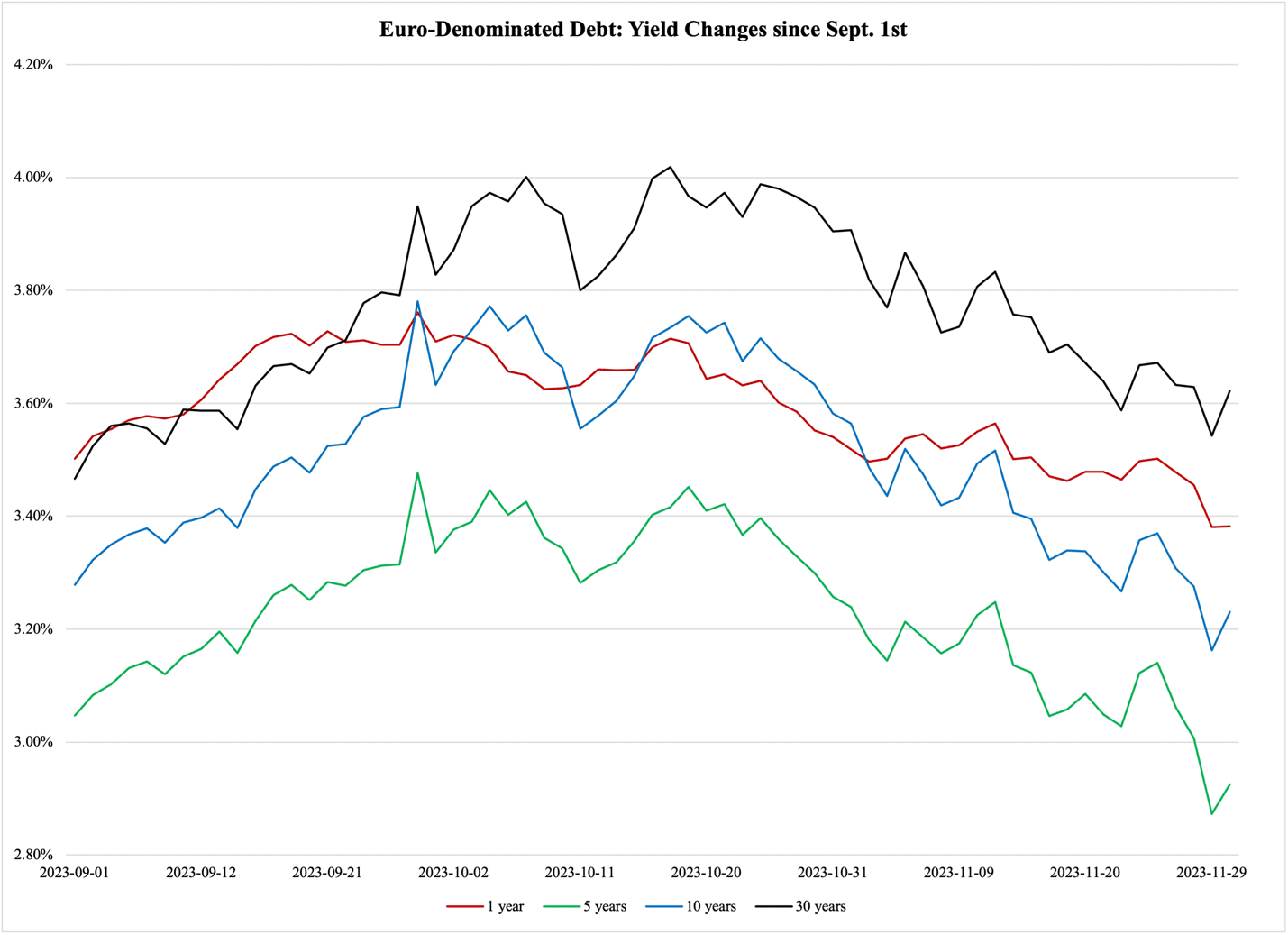

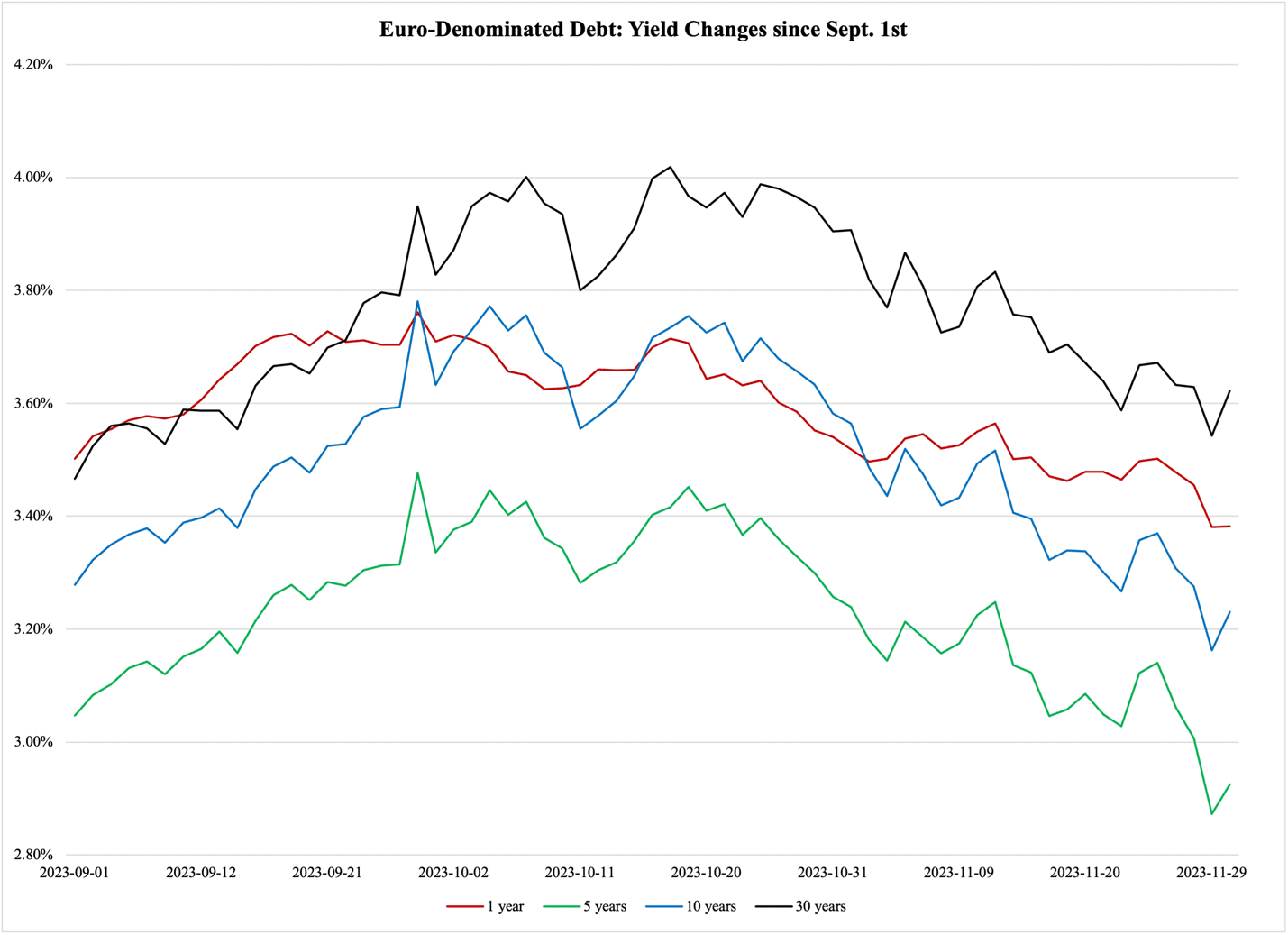

We are unlikely to see a return to the low pre-pandemic yields, at least over the next year. At the same time, we seem to have just passed the peak of high interest rates. Figure 2 reports the recent decline in sovereign debt yields:

Figure 2

Since their peak in mid-October, sovereign debt yields have generally come down 0.4-0.5 percentage points, wiping out the rise in yields in the previous six weeks. Again, this does not amount to much in the context of the last couple of years’ worth of rising interest rates, but it will bring some alleviation to both governments and the private sector in euro zone countries.

The fall in debt yields will be a welcome easing for governments that see the recession eat away at their tax revenues. New deficits will force governments to issue new debt, but with lower borrowing costs.

This will be particularly good for the six euro zone countries that have a consolidated government debt above 100% of GDP: Greece (172.6%), Italy (141.7%), Portugal (112.4%), France (111.8%), Spain (111.4%), and Belgium (104.3%). These countries have a more pressing problem than less-indebted countries with rolling over their debt. When a treasury security is issued, it comes with a maturity date; when that date is reached, the indebted government has to pay back the principal of the loan. It can do so with current tax revenue, or by selling a new debt instrument.

In the former case, the government reduces its debt; in the latter case, it runs the risk of raising the cost of its own debt because interest rates have gone up since the original debt security was issued. Suppose, e.g., that a euro zone government issues 2-year treasury bills on October 15th, 2021. At that time the yield was negative at -0.58%. When that bill matured this past October, the yield was 3.24%.

In other words, for every €1 million that this government borrowed two years ago, it did not pay anything—it earned €5,800 per year. Technically, the government paid back the owner of the debt less than it borrowed, namely €11,600. By contrast, over the next two years, the same €1 million worth of 2-year debt will cost this government €32,400 per year.

The total rise in cost of the debt amounts to €38,200 per year on this €1 million debt. If we scale this up, the cost hike due to rising interest rates over the past two years can be considerable for a deeply indebted government. By the same token, the decline in rates, though small, eases the debt burden and leaves more of taxpayers’ money in the government’s general fund.

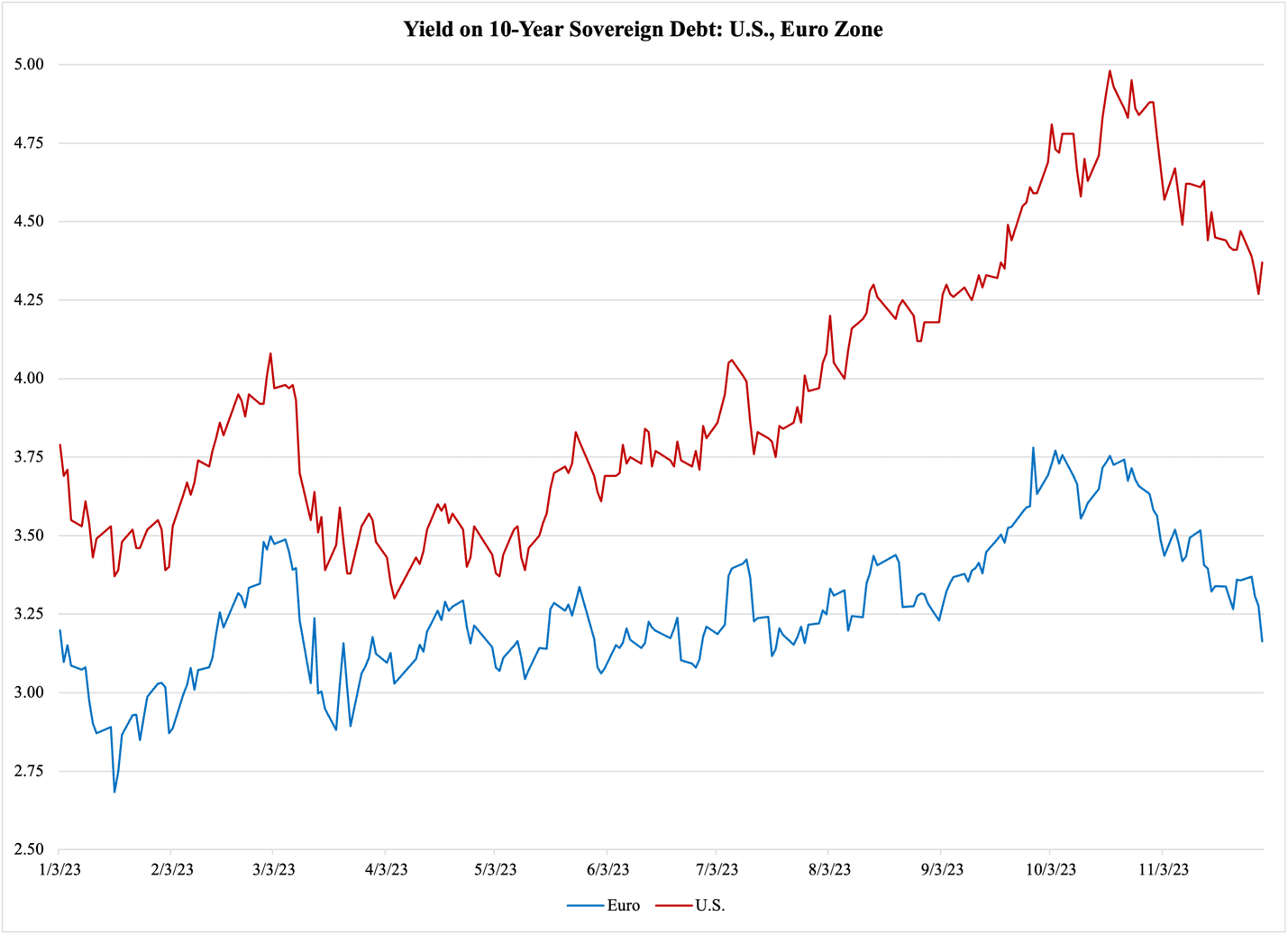

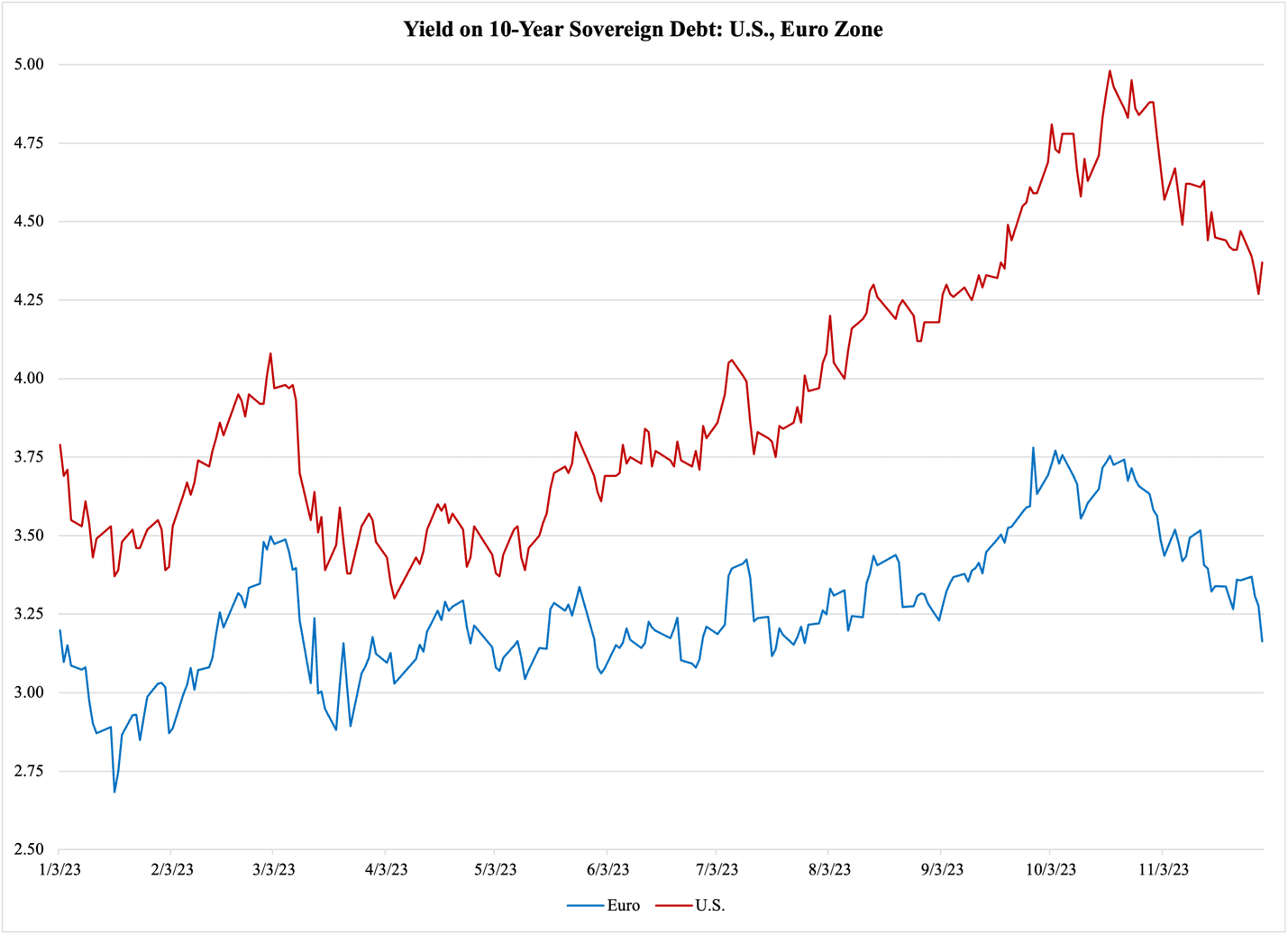

The big question, then, is: will interest rates continue to decline? That depends on what policy decisions the ECB makes, but only to some degree. Yields on euro-denominated sovereign debt are closely correlated with yields on American sovereign debt. Figure 3 reports this year’s yields on the 10-year notes from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean:

Figure 3

The Federal Reserve holds its next policy meeting on December 12-13. Its decision will undoubtedly affect the outlook for the yields on euro-denominated debt as well. It would be very surprising if the Fed raised its rates; a far more likely outcome of the meeting is that it keeps its federal funds rate—the Fed’s leading monetary policy indicator—unchanged for now. This will have a reassuring effect on the U.S. debt market; investors will interpret it as a preamble to rate cuts in the spring of 2024.

If this is the outcome of the Fed’s meeting next week, we can expect a similarly positive outlook on interest rates in the euro zone. This would mean that the current trend would be reinforced and continue to ease the costs of borrowing for Europe’s currency area governments.

With a recession unfolding, this would be much-needed good news for member state governments, and of course for taxpayers.