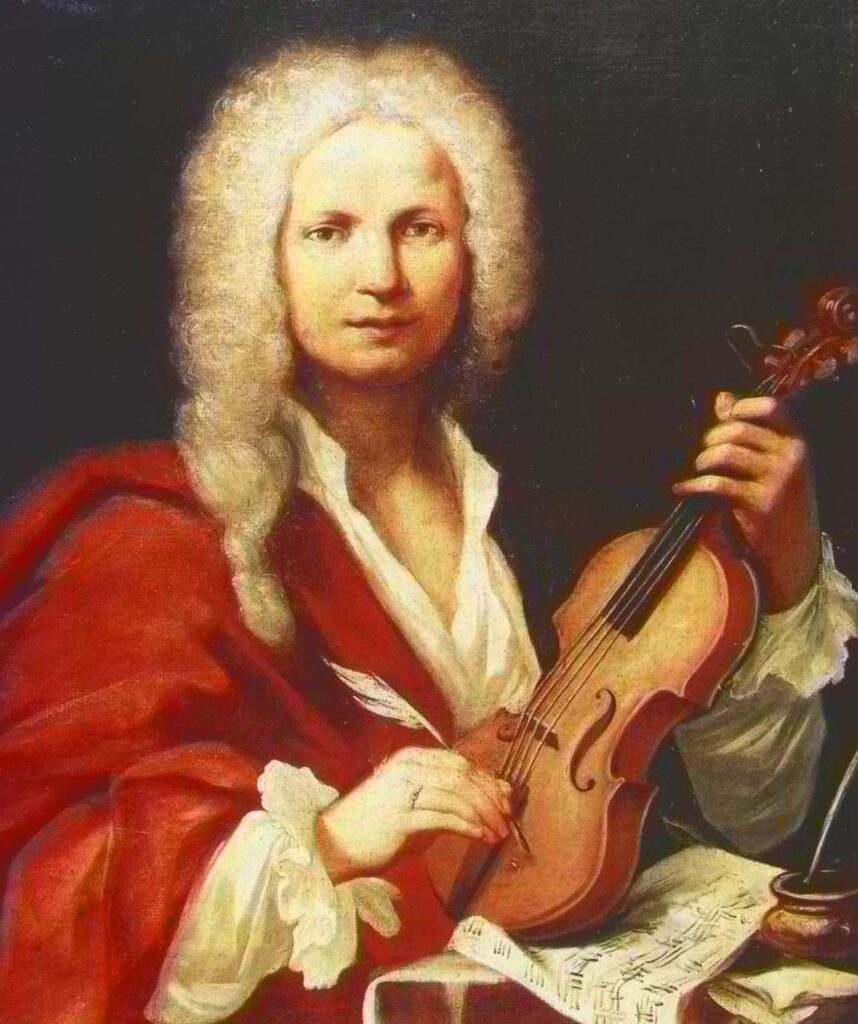

Detail of the painting Concert in a villa (1739-1740), an oil on canvas by Antonio Visentini (1688-1782), located in the Palazzo Contarini Fasan in Venice.

This composer, who was both priest and artist—a combination common in Italy—was one day reciting Mass. When he had arrived at one of the most important passages of these venerable and sacred mysteries, he was suddenly seized by an artistic inspiration and felt the most urgent need to write down part of a suddenly emerged composition that his genius had just dictated to him. He pays no heed to what he does and says. The temple in which he practices the most sacred and inviolable of all mysteries, the altar on which he officiates, the priestly garb in which he is clothed, the sacred words he utters, all this he forgets and runs … where to? … Vivaldi runs to the sacristy, where he first notes a fugue theme at his leisure, before returning to finish the mass, to the immense astonishment, as one can imagine, of all the faithful who formed his pious audience at that moment. This crime, or rather this aberration of the mind, was reported to the Inquisition, which, however, out of an indifference more indicative of wisdom than contempt, spared Vivaldi the punishment that would have long prevented him from making such a mistake again. He was considered a madman and a musician, which in the eyes of Torquemada’s heirs [i.e., the Inquisition’s] more or less amounted to the same thing.

—Grégoire Orloff [Count Grigory Vladimirovich Orlov, 1777-1826], Essai sur l’histoire de la musique en Italie, depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu’à nos jours, Paris, Vol. II, 1822, pp. 289-290.

The Venetian priest, violinist, and composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) is not bothered by either God or commandment when he hears the luring voice of musical inspiration: it is undoubtedly a fascinating story that Count Orlov recorded in his Italian music history in 1822. But is it true? Where and when he heard or read this anecdote, Orlov unfortunately does not tell. As is so often the case, it is quite possible that historical reality and literary fantasy are mixed up here. In any case, a strong and impulsive personality Vivaldi certainly was. Once, when he was at odds with the painter and scenographer Antonio Mauro, he abused his priestly status in a shocking way by accusing his opponent of “il peccato dell’ingratudine” (the sin of ingratitude) and of “insinuazioni diaboliche” (devilish allegations). “Iddio vede, Iddio sà, e Iddio giudica” (God sees, God knows, and God judges), Vivaldi added.

Such hotheadedness ran in the family: Antonio’s father Giovanni Battista was sentenced to six months in prison in October of 1675 after physically attacking an assistant priest. And Antonio’s brother Iseppo Gaetano was banned from Venice for three years in November of 1728 after stabbing an errand boy in the face with a knife. Francesco Gaetano, another younger brother, had to pay with years of exile for severely insulting a Venetian nobleman. All these incidents certainly did the name of the Vivaldi family, which belonged to the lowest social class to start with, no favours among the Venetian nobility. It is therefore no coincidence that Antonio was rather reluctantly supported by that Venetian nobility during his career. Striking evidence of the contempt that many representatives of the Venetian upper class felt for Vivaldi is the sarcastic outburst that the nobleman and literary man Antonio Conti allowed himself, after mentioning Vivaldi’s great success with the Habsburg emperor Charles VI in a letter: “Schiavo Signor Cavalliere!” (Slave becomes Lord Knight!). But Antonio compensated for this condescension from the Venetian nobility with his unstoppable energy and enormous talent, so that as early as 1706 the Guida de’ Forestieri, a well-known travel guide for visitors from outside Venice, counted him, along with his father, among the best violinists in the city.

Much more is known about Vivaldi’s training as a priest than about his training as a violinist and composer. Thus, we know that he received the tonsure on the 18th of September, 1693, and was ordained a priest on the 23rd of March, 1703. In those same years, Antonio grew into an internationally renowned violinist and composer, but under whose guidance remains unknown. His father Giovanni Battista Vivaldi (ca. 1655-1736) was a respected violinist in Venice and is likely to have been Antonio’s violin teacher and possibly first composition teacher. Music historians used to assume that the famous Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690) also gave Antonio composition lessons. However, there is no evidence for this. Moreover, Legrenzi died in 1690, shortly after Antonio turned twelve. It is noteworthy that Vivaldi plagiarised pieces by Antonio Lotti (1666-1740) and Giovanni Maria Ruggieri (ca. 1669-1714) in some of his works. Did either of them perhaps initiate Vivaldi into the deeper principles of counterpoint, the art of learned polyphony? It is frustrating, maddening even, for anyone who loves Vivaldi’s music that such basic data on his development as a composer and musician is lacking to this day. Hopefully, this will finally change in the near future: English researcher Micky White, who lives in Venice, is dedicating her life to scouring the Venetian archives for unknown data on Vivaldi, with sometimes remarkable results. Who knows? Maybe she will one day solve the mystery behind Vivaldi’s musical education.

Back to Orlov’s anecdote. It suggests that Vivaldi was as much an inspired composer as he was a negligent priest. But where did that idea come from? And is it accurate? We have already seen that he sometimes abused his priestly status, but that does not necessarily mean that he was an indifferent priest. In fact, the latter is unlikely. When the poet and librettist Carlo Goldoni visited the composer in his own house in 1735, Vivaldi was deeply absorbed in the praying of his breviary. Yet there were bad rumours about Vivaldi. At the end of 1737, Vivaldi received word in Venice that the cardinal archbishop of Ferrara forbade him to travel to Ferrara to perform some of his operas. In his famous letter, of the 16th of November, 1737, to a patron, Vivaldi explained that he was accused of no longer offering Mass and maintaining an amicizia (‘friendship,’ a euphemism for ‘relationship’) with his favourite prima donna, the singer Anna Girò. Literally, he writes:

For 25 years I have not read Mass and never will do so again, not because of any prohibition or command, but […] of my own choice, and this because of an ailment from which I have suffered since birth. That ailment was the cause of my having read Mass almost immediately after my ordination for only a year or a little longer, but ceased to do so after I had to leave the altar three times without finishing Mass as a result of that same ailment.

Is it true what Vivaldi writes here or is he making a desperate attempt to save his reputation? I think we should take him at his word. Indeed, it was recently revealed that from September of 1703 to November of 1706, Vivaldi read Mass in the church of the Ospedale della Pietà (an institution for abandoned children) and was well paid for it, better even than in his parallel job as a violin teacher at the same institution. Why would Vivaldi have given up this lucrative combination of jobs if there was no clear need to do so? Moreover, in the letter quoted above, he fully acknowledges the fact that he had been forced to leave the altar several times. A churchgoer may have pointedly remarked that the priest-composer surely wanted to write something down quickly and voila!: a good anecdote was born. Vivaldi’s prosaic explanation, that his asthmatic condition forced him to stop reading Mass, may simply be true.

Vivaldi never fully recovered from the ‘tragedy of Ferrara.’ A French traveller who met him in 1739 remarked, astonished, that Vivaldi was not as highly regarded in his own city of Venice as he would deserve. For this reason, the 62-year-old ‘prete rosso’—Vivaldi owed his nickname ‘red priest’ to his fiery red hair inherited from his father—decided to turn his back on his hometown and move to Vienna in May 1740. Perhaps he hoped for the support of the aforementioned Emperor Charles VI, a great admirer of Vivaldi’s music, and other Habsburg noblemen living in Vienna with whom Vivaldi had corresponded for many years. Almost certainly he had opera plans for Vienna, whether or not invited to do so by the Theater am Kärtnertor. However, Charles VI died on the 20th of October, 1740, after which all theatres had to close for fourteen months as part of the national mourning. In 1742, a year after Vivaldi’s death in the night of the 27th of July, 1741, the opera L’Oracolo in Messenia, probably planned for Carnival 1741, would finally be performed at the Theater am Kärtnertor.

Like his German contemporaries Handel and Telemann, Vivaldi strove to be a ‘universal composer,’ i.e. he practised all genres imaginable in his time. The Répertoire Vivaldien (RV), in its second edition, edited by Federico Sardelli, lists more than 800 works, ranging from solo sonatas, trio sonatas, concertos and symphonies for string orchestra, solo concertos for a wide variety of instruments to sacred choral works, solo motets, oratorios, solo cantatas and operas. This was unusual in the Italy of the time, where most composers specialised either in instrumental or vocal music. Fellow violinist and composer Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) therefore reproached Vivaldi for not distinguishing enough between the neck of a violin and the throat of a singer. The German composer and theorist Johann Mattheson (1681-1764) emphatically contradicts this accusation and praises Vivaldi’s writing for the voice.

Vivaldi achieved fantastic results in all genres. But in music history, his greatest contribution clearly lies in the field of the solo concerto, to which he gave a rich and balanced three-movement form. Vivaldi’s example set the marching path for many decades after his death. Most of his concertos Vivaldi probably composed for the Venetian Ospedale della Pietà, a home for foundlings founded in the first half of the 14th century, where unwanted—often illegitimate and sometimes disabled—children were cared for. An 18th century Dutch traveller spoke bluntly of ‘whore children.’ It is often claimed that only girls and women stayed at the Pietà, but this is incorrect. The male foundlings were trained to become craftsmen and left the institution when they reached the age of 18. The girls stayed at the institute until their death, unless a suitor showed up or entry into a convent was a possibility, which was only rarely the case. For this reason, the choral singers and orchestral musicians needed, among other things, for the musical accompaniment of the liturgy in the chapel of the Pietà, the Santa Maria della Visitazione, were recruited exclusively from among the female residents. After all, why invest in expensive musical training for the boys when they left the nest early?

The girls who were admitted to the coro, the so-called figlie di coro, formed an élite within the institute and were exempt from all kinds of domestic duties (‘tasche’ or ‘lavorieri’). For obvious reasons, their surnames are unknown, and they are referred to in archival documents as ‘Antonia dal Tenor’ (‘Antonia singing tenor’), ‘Clementia dal Violin,’ ‘Giulia Organista,’ and so on. The figlie di coro were trained and taught by a small group of paid male musicians: the maestro di coro and music teachers for solfège, singing, violin, and other instruments. Beyond that, the women were largely self-reliant; the more advanced singers and musicians among them taught the beginners. A spectacular fact: the women who formed the choir in the Pietà probably sang the tenor and bass parts at the pitch notated by the composer, and thus not an octave higher, as was often taken for granted in the past. The standard of musical performances by the women and girls was so high at the time of Vivaldi’s appointment as violin teacher and maestro de’ concerti that the publicly accessible concerts given after church services were legendary throughout Europe. A 1718 list of figlie di coro gives 59 names. Perhaps the most prominent figlia di coro at the time was violinist Anna Maria (1696-1782), who was admitted to the coro in 1720 and for whom Vivaldi composed a large number of violin concertos and also at least two concertos for viola d’amore. Vivaldi must have felt a special affection for her, otherwise he would not have incorporated her initials ‘AM’ in capitals in the title of the two concertos for viola d’AMore RV 393 and RV 397.

It is certain that many of Vivaldi’s sacred choral works were also commissioned by the Ospedale della Pietà. Sometimes the maestro di coro (‘choirmaster’) suddenly disappeared from view, like Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727), whom we have encountered before in Domenico Scarlatti’s biography. Gasparini had requested and received six months’ leave from the governors of the Pietà on the 23rd of April, 1713, for health and urgent family reasons. But Gasparini would never return to his post. This offered the institute’s violin teacher—that is, Vivaldi—a unique opportunity to prove himself as a composer of sacred music as well. He had already some experience in this field. It is certain, for instance, that Vivaldi had composed his moving Stabat mater RV 621 for Brescia a year earlier. In any case, the governors of the Pietà allowed Vivaldi to jump into the gap created by Gasparini. He apparently functioned so well as choirmaster ad interim that the Pietà did not appoint a new maestro di coro in the person of Carlo Luigi Pietragrua (ca. 1665-1726) until February of 1719. During that period of almost six years, Vivaldi composed, among others, the now world-famous Gloria RV 589. In general, it is notable that Vivaldi sometimes delivered raw edged works in almost all genres, but this is rarely, if ever, the case in his sacred works. Their average level can definitely be called spectacularly high.

Nevertheless, during his lifetime, Vivaldi was much less influential as a composer of sacred music than as a composer of solo concertos. In the latter genre, as noted earlier, he was the grandmaster recognised throughout almost all of Europe. Virtually no contemporary composer of solo concertos could or would ignore his example, although there are exceptions like Christoph Graupner (1683-1760) and also George Frideric Handel (1685-1759). None other than Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) arranged six of Vivaldi’s concertos for solo harpsichord, three for solo organ, and the Concert for four violins, strings and basso continuo in b minor RV 580 into the Concert for four harpsichords and strings BWV 1065. (Bach’s arrangement, in turn, inspired Schumann to compose his Concertstück for four horns and orchestra, Op. 86!) Six of these ten concertos Bach had found in Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico, Op. 3, a collection of twelve concertos published in 1711 by the Amsterdam publisher Estienne Roger, which made a big impression all over Europe immediately after its publication. Yet it was a later publication that was regarded as even more characteristic of the composer’s style during Vivaldi’s lifetime: the twelve concertos, Op. 8, entitled Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (‘the proof of harmony and ingenuity’). Let us dwell a little longer on this unique opus …

In (or shortly before) 1720, Vivaldi sent his opus 8 to his Amsterdam publisher Michel-Charles Le Cène, who had taken over the business of his late father-in-law Estienne Roger in 1721. Why it took no less than five years before the concertos were published in 1725 is unclear, but when they finally rolled off the presses, they quickly became an international hit. The success of opus 8 was, and is mainly caused by, the first four violin concertos from the collection: The Four Seasons (Le quattro stagioni). The Four Seasons—and in particular the first concerto, Spring (La primavera)—kept Vivaldi’s name alive for several decades after his death, especially in France.

The edition is accompanied by an intriguing but at the same time sometimes confusing dedication addressed to the Bohemian Count Wenzel von Morzin. In the said dedication, Vivaldi apologises to the count for the inclusion of The Four Seasons in opus 8, because the count has known these works ‘for such a long time’ (‘da tanto tempo’). However, Vivaldi adds that he is confident that The Four Seasons will strike Morzin as new since he has added to the music “apart from the sonnets, a very clear explanation of all the things expressed in them.” These words raise several questions. What exactly is the relationship between the music and the words that represent what the music is about? And had Morzin come to know the music with or without the sonnets? The Amsterdam edition contains four anonymous sonnetti dimostrativi (‘illustrative sonnets’) whose contents are so meticulously reflected in the music that it is logical to assume that it was Vivaldi’s main goal to translate these poems into music as literally as possible. But the rather obscure meaning of the quoted passage from the dedication letter, as well as some facts not mentioned in this context, do not unreservedly support this theory. According to Paul Everett, author of an excellent book on The Four Seasons, Vivaldi’s starting point may have been a prose scenario rather than the four poems. Having written the music along the lines of the scenario, Vivaldi realised that most players and listeners would not fully understand what the music was about without further explanation. For this reason, Vivaldi or a collaborator wrote four sonnets ‘based on’ (‘sopra’) the four concertos. For the edition of The Four Seasons, Vivaldi then felt the need to explain the content of the music even more precisely by adding short captions (e.g. ‘the barking dog,’ ‘the farmer’s lament,’ ‘the drunkard,’ and so on). As we have seen, these inscriptions were in any case new to Morzin, unlike the sonnets that seem to have accompanied the music sent to Morzin from the beginning, although, as mentioned, Vivaldi’s dediction is not entirely clear in this respect. Finally, the dedication was written after Vivaldi had learned that opus 8 would finally be published.

Whatever the precise nature of the text-music relationship in The Four Seasons, the miraculous thing about these four masterpieces is that, on the one hand, they evoke extra-musical events and phenomena in a highly suggestive way, while, on the other, they are so completely convincing in a purely musical sense. Especially in France, The Four Seasons were widely admired until several decades after Vivaldi’s death. Jean-Philippe Rameau, the greatest French composer of the 18th century, borrowed several passages and ideas from Summer, Autumn, and Winter when he composed his Anacréon in 1757. Michel Corrette (1709-1795) used Vivaldi’s Spring as the musical base for his setting of Psalm 148 (‘Laudate Dominum de coelis’) for soloists, choir, and orchestra, published in 1766. Finally, the renowned philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau arranged the same concerto for flute solo as late as 1775.

The continued interest in Spring throughout France in particular was exceptional, for Vivaldi’s compositions were generally forgotten soon after his death. Some concertos from L’estro armonico, Op. 3, La stravaganza, Op. 4 and Il cimento, Op. 8, were still occasionally put on the music desks, also outside France. Nevertheless, from the second half of the 18th century, Vivaldi’s name was hardly more than a footnote in the history books. And if he is mentioned at all—as in 1806 by the composer and writer Johann Friedrich Reichardt—disparaging qualifications like ‘leer und unbedeutend’ (‘empty and insignificant’) often follow. Yet, ironically, it was a German contemporary of Reichardt, the composer and theoretician Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818), who laid the foundations for the rediscovery of Vivaldi’s music. Indeed, in his book Über Johann Sebastian Bach’s Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke (Leipzig, 1802), Forkel writes that Bach only managed to bring ‘Ordnung, Zusammenhang und Verhältnis in die Gedanken’ (‘order, coherence and proportion in the motives’) to his compositions after having studied and arranged Vivaldi’s violin concertos. This is an exaggeration, but it is true, that beginning in his years in Weimar (1708-1717), Bach demonstrably started imitating aspects of Vivaldi’s music, such as Vivaldi’s three-part concerto form, and even certain characteristic musical gestures of the Italian.

The fact that the great Bach had taken such an interest in Vivaldi’s concertos posed a problem for many 19th century German writers on music. Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski, for instance, in his book Die Violine und ihre Meister (Leipzig, 1869), acknowledges that Vivaldi significantly improved the form of the solo concerto, but asserts at the same time, that the Italian wrote music without ‘tiefere Empfindung’ (‘deeper feelings’) and ‘wahrhafte Kunstweihe’ (‘true artistic consecration’). Certainly, Bach had learned from Vivaldi how to compose a truly Italian solo concerto, Wasielewski was willing to admit, but he immediately added that Bach’s arrangements relate to Vivaldi’s originals like graceful flower arrangements to sparsely overgrown lawns.

And yet, every now and then, someone had an eye and ear for Vivaldi’s originality, even in 19th century Germany. German violinist Edmund Medefind, for instance, arranged Vivaldi’s exuberant Concerto for three violins, strings and basso continuo RV 551 for three violins and piano. The critic of the Dutch musical magazine Caecilia heard a performance of it in The Hague on the 9th of December, 1885. In his opinion, the concerto betrayed “entirely Bach’s style” and was “so interesting in content” that it should be performed again soon! However, this appreciation of Vivaldi’s music would only gain ground after the publication of the book Geschichte des Instrumentalkonzerts bis auf die Gegenwart (Leipzig, 1905) by German musicologist Arnold Schering. Schering’s praise was part of the reason why the French musicologist Marc Pincherle decided to dedicate his doctoral thesis to Vivaldi, a project that culminated in the monumental publication Antonio Vivaldi et la musique instrumentale (Paris, 1948). The second reason, incidentally, was a forgery: the famous Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) wrote a violin concerto around 1906, which he presented as an unknown work by Antonio Vivaldi and performed with great success all over Europe. Later, Kreisler had to acknowledge that he himself was the author of the piece. But then Pincherle, who had been deeply impressed by Kreisler’s forgery, had already spent many years of his life studying Vivaldi!

In Italy at the same time, people were not exactly sitting still either. There, the rediscovery of Vivaldi’s personal music archive—the first half in 1926, the other half in 1930—had led, among other things, to the ‘Settimana Vivaldiana’ (‘Vivaldi Week’), which took place in Siena from the 16th to the 21st of September, 1939. For the first time in modern times, in addition to instrumental works, sacred compositions—including the Gloria RV 589 and the Stabat mater RV 621—and even the Serenata a tre RV 690 and the opera L’Olimpiade RV 725 were performed, albeit in the form of arrangements, for which in most cases the composer Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) was responsible.

After the end of World War II, there was no stopping it. Powerfully supported by the foundation of the Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi, the start of the complete publication of the instrumental works by the Ricordi publishing house and the emergence of one specialised chamber orchestra after another, the name Antonio Vivaldi gradually became a cast-iron ‘brand.’ The recording industry also threw itself into his music. Whereas in 1956 there were only about 200 recordings of Vivaldi’s music on the market, by 1978 there were at least 700. The proliferation of recordings of The Four Seasons was already a fact by then. According to connoisseurs, there is no work in the classical catalogue that has been recorded more often than The Four Seasons. All this attention is wonderful news for the appassionati of Vivaldi’s music, to whom I have belonged practically my whole life. But there is also a downside: Vivaldi currently dominates the picture of Italian composing in the 18th century to such an extent that great contemporaries like Francesco Bartolomeo Conti, Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco, and Francesco Geminiani hardly get the attention they deserve on the basis of their musical significance. To be clear, I do not mean to say that I consider these composers as important as Vivaldi, but rather that they can hardly step out of his shadow, unjustly. Of course, we see this all the time in art and music history: even the less successful works of generally recognised masters like Rembrandt and Bach are ascribed a mythical significance—and thus literally a higher financial value than the best works of their principal contemporaries. In my opinion, one can lament that fact without in any way detracting from the indeed unparalleled level of the best works of the grandmasters.

In Vivaldi’s case, it is important to choose well. Vivaldi has a unique, instantly recognisable style of his own, which you may or may not like, and he can sometimes combine genius movements with completely routinely composed movements in the same work. He may admittedly be an uneven composer, with high peaks and deep valleys, but Vivaldi is, as far as I am concerned, the most idiosyncratic composer of his time. That is the reason why I often compare him to Hector Berlioz, the 19th century French composer who, averse to academic rules, developed a highly experimental, personal, and controversial style, which to this day has as many detractors as admirers. The boundless energy and eye-catching originality of Vivaldi’s music have sometimes been interpreted as compensation for the fact that he was sickly and dependent on others in everyday life. This is certainly possible, but hereditary factors may also have played a role here: as noted earlier, the Vivaldis were known for their fierce temperament.

A small anthology of brilliant pieces in exemplary performances starts, of course, with The Four Seasons. I only mention here Monica Huggett’s recordings with The Raglan Baroque Players from 1990 (Virgin Classics) and Janine Jansen’s from 2004 (Decca). Of twelve of Vivaldi’s early violin concertos, Florian Deuter (baroque violin) and Harmonie Universelle offer an unforgettable interpretation (Eloquentia, 2007). Vivaldi’s late violin concertos have been brilliantly recorded by Giuliano Carmignola and the Venice Baroque Orchestra conducted by the great Andrea Marcon (DGG). Sergio Azzolini, playing on the reconstruction of a Venetian baroque bassoon (made by Dutch instrument maker Peter de Koningh), has until now recorded 33 of Vivaldi’s 39 bassoon concertos (two of which are incomplete) on the Naïve label (5 CDs). For the moving Stabat mater RV 621 and the sublime Nisi Dominus RV 608: listen to James Bowman (countertenor) with The Academy of Ancient Music (Decca). English countertenor Tim Mead, who gave an unforgettable performance of the Nisi Dominus in the Matinee of 17 September 2022, has now also beautifully recorded the work on CD (Alpha). There are many good performances of the famous Gloria RV 589—there is also another, much lesser-known but equally beautiful Gloria RV 588. Sir John Eliot Gardiner has the sublime Monteverdi Choir at his disposal for his performance (Archiv). Among the recordings of Juditha triumphans—unfortunately the only one of Vivaldi’s four oratorios known by name whose music has survived—the interpretation conducted by Alessandro De Marchi (Opus 111) throws high marks. Of the masterful ‘serenata’ La Senna festeggiante RV 693, the earliest recording conducted by Claudio Scimone is still my favourite (Italia). Those who do not want to hear an entire opera by Vivaldi right away can start with the two CDs of highlights made by Cecilia Bartoli in 1999 and 2018 (Decca). Among the operas, L’incoronazione di Dario, Giustino, Orlando Furioso, La fida ninfa and Farnace—all five of which appeared on the Naïve label and all but L’incoronazione have also been performed with great success in concert at the NTR Saturday Matinee—are my preferred titles.