Finland is suffering from labor unrest. Finnish state news agency Yle.fi reports (original article in Swedish):

Unions are declaring political strikes on February 1st and in some cases also February 2nd. The unions will protest the government’s labor market reforms and reforms that will affect the right to strike.

According to other news sources, the protest is also directed against proposed reforms of the social-benefit system under the Finnish welfare state.

Swedish news site Arbetsvärlden elaborates (party affiliation in parentheses):

Prime Minister Petteri Orpo (M) and Finance Minister Riikka Purra (Finns Party) are determined to improve the Finnish government’s bad fiscal situation … The government wants, among other things, to see major increases in the fines for illegal strikes, and has a list of proposals for cuts in a variety of entitlements and benefits.

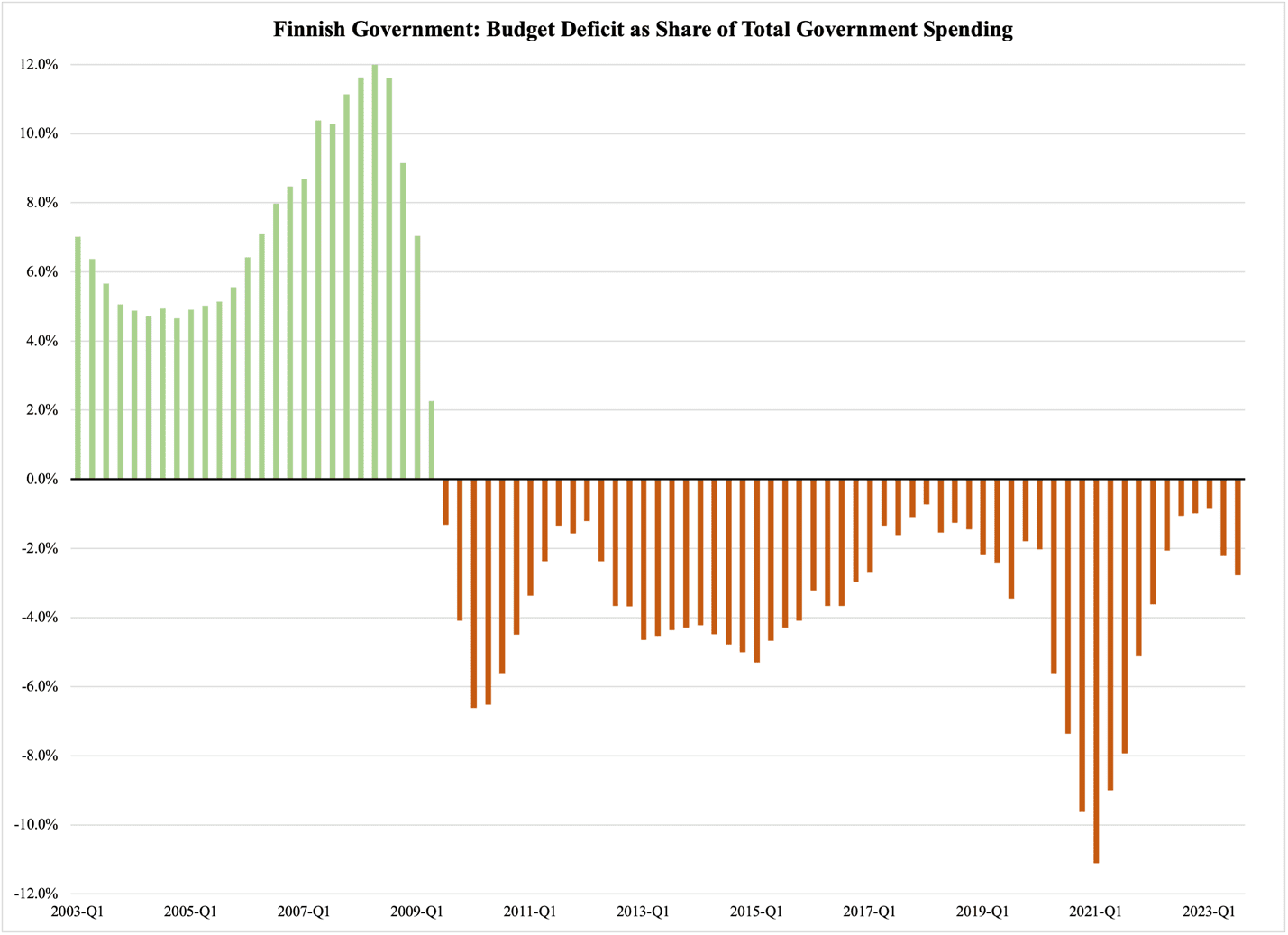

The government in Helsinki is absolutely correct: Finland is in dire need of fiscal reforms. To start with the most precarious problem: a chronic budget deficit. Figure 1 reports budget surpluses as green columns and deficits as red columns; they all measure the budget balance (surplus or deficit) as a percentage of total government spending:

Figure 1

The shift from surpluses prior to 2009 to perennial deficits thereafter is no coincidence. Let us get back to the details in a moment. First, Figure 2 gives us a clue as to where those deficits come from:

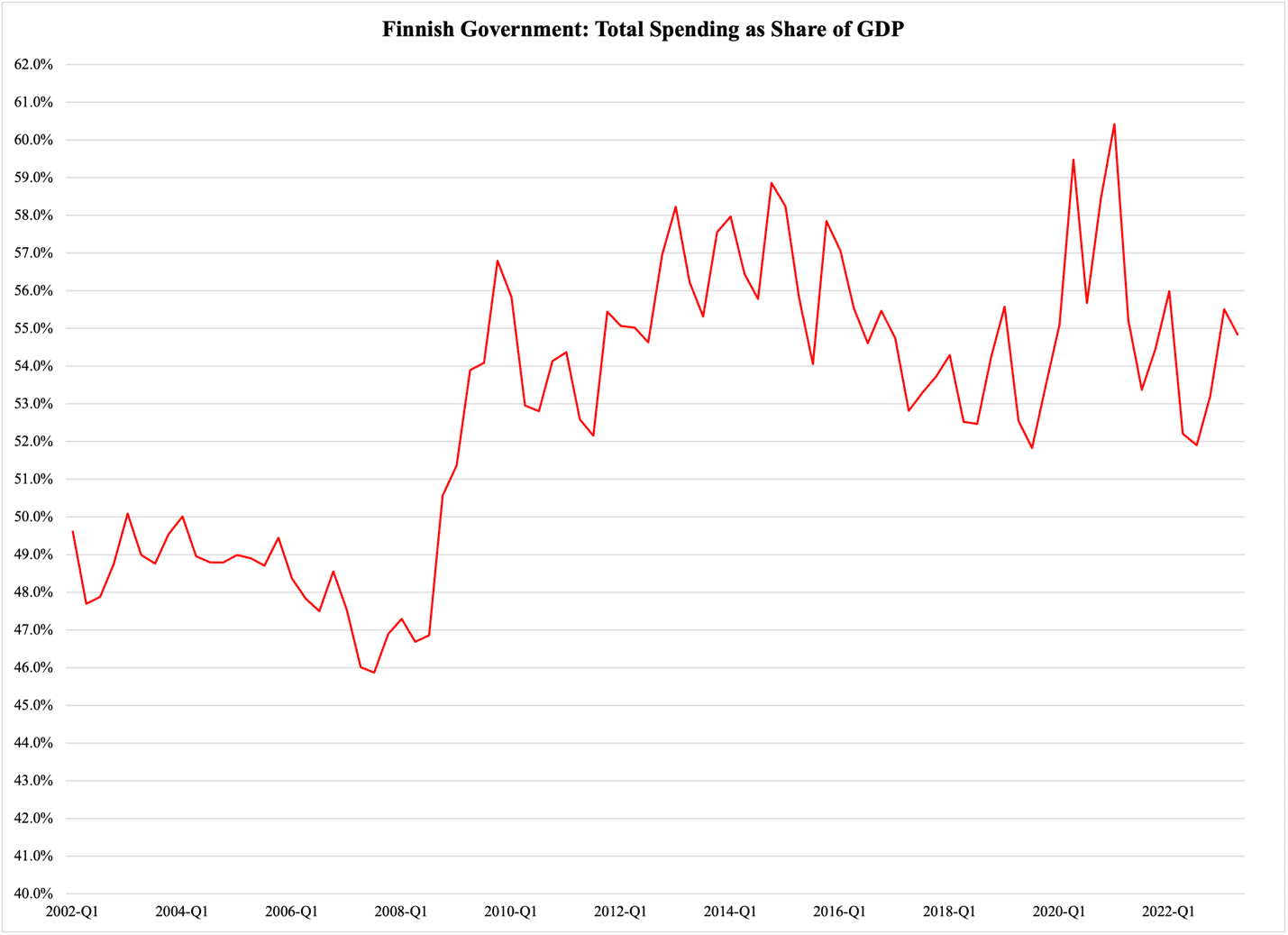

Figure 2

In a matter of two years, government spending increased from 46.6% of GDP in 2007 to 53.9% in 2010.

This kind of increase is almost impossible to find in modern, mature welfare states. It is characteristic of a country that is in the process of constructing its welfare state, but Finland is no novice to government spending. The country has an old, mature Nordic-style welfare state.

This expansion of government spending is big enough to send a shockwave through the economy. Which, unsurprisingly, is exactly what happened:

In fact, in 2012-2015, the Finnish economy contracted by -0.5% per year. Although a small number, it is nevertheless a conspicuous ‘achievement.’ These were the best years of the economic recovery from the Great Recession in 2008-2010, when the global economy was doing relatively well. For comparison, during the same period, the economy of the current 27 EU member states expanded by 0.8% per year. This is not a spectacular number, but it is 1.3 percentage points better than what the Finnish economy mustered.

By growing government in this way, the Finns have statistically speaking lost out on two percentage points’ worth of real GDP growth per year since 2010. This may sound like a mere technicality, but it is not: if the economy had indeed grown by another 2% per year, today the Finnish GDP would be 31.6% larger than it is today—adjusted for inflation.

Let us take a look at what this means in the real world:

But more than anything, GDP is the broadest possible tax base from which government can get revenue to pay for all the services and benefits it provides its citizens. If the Finnish economy had continued to grow in 2010-2019 as it did in 2000-2009, the consolidated public sector would have had approximately €8.6 billion more in tax revenue (assuming an unchanged tax-to-GDP ratio). After closing the budget gap, there would have been enough revenue for the government to lower taxes by the equivalent of a little bit more than 10% of GDP.

These are enormous tax cuts, although it is important to keep in mind that they are an estimate based on a static analysis of the Finnish economy as it looked in 2019. A dynamic analysis would probably yield a different result.

Nevertheless, these numbers give us a good idea of the magnitude of the economic losses that Finland suffered from the great 2009 expansion of government.

But what was it that they actually did back then? We get a good idea of what happened by disaggregating government spending. In the first decade of this century, i.e., from 2000 through 2009, spending on social protection (including but not limited to cash benefits for the unemployed as well as for lower-income households) by the Finnish government increased by 4.4% per year. This was an average level of increase for government as a whole; outlays on housing, health care, environmental programs, and education all grew faster than social protection spending.

In 2010-2019, the social protection programs grew more slowly, at 3.5% per year. However, in this decade, all other programs (except art subsidies) grew more slowly. In some cases, such as defense, environmental programs, and housing, spending actually fell.

Since social protection accounts for 44% of all government spending in Finland, its expansion during 2010-2019, although slower in actual numbers than in the decade before, became the engine of a growing government.

As such, it also became the driver of Finland’s economic stagnation. No economy can survive for an extended period of time with government spending at 54% of GDP. The stagnant nature of the Finnish economy is a direct result of its massive welfare state: as government grows, more economic resources are funneled through a system where resources are not allocated based on free-market principles, but on political decree.

It is legislation, not the forces of the free market, that determines how €54 of every €100 shall be used in the Finnish economy. Since the distribution of all that money is guided by political preferences, not the will of the people expressed through market forces, the outcome is inevitably inferior to what the free market would have done.