As a young boy, I looked forward to Sunday afternoons, when I would climb onto my father’s lap, and he would read me the colorful comics included in our Sunday paper. These comics (which my father has always called “the funnies”) were almost all comedic. Whether thoughtful and poignant like Peanuts or childish and predictable like Garfield, the silly jokes in these comics kept me entertained, week-in and week-out.

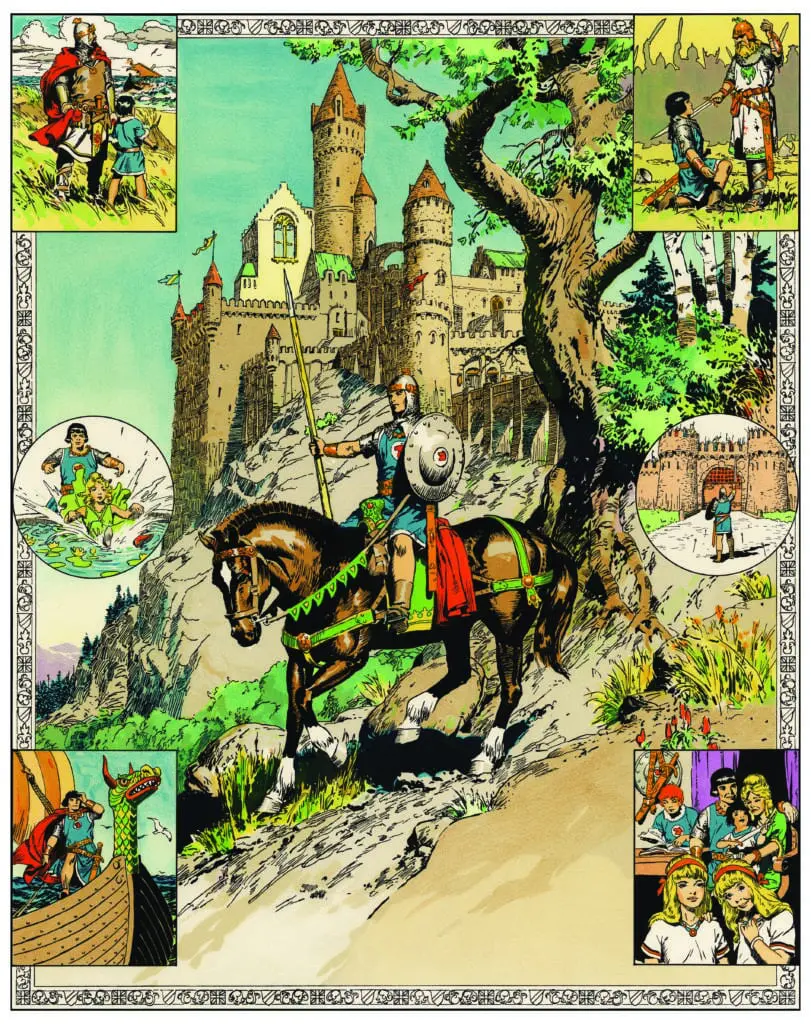

However, there was one comic that was unlike any other: Prince Valiant. Its art style was far more like a painting than a doodle, it took place in the days of King Arthur, and it didn’t even use speech bubbles for dialogue. By the time I was a boy, my local paper printed an extremely small version that rarely held my interest (despite the excellent work of John Cullen Murphy, who wrote and drew the comic at that time). Little did I know that I was missing out on the greatest adventure comic strip of all time. The strip had begun in 1937 as a beautiful, sprawling epic that took up an entire newspaper page each week with Hal Foster’s trailblazing illustrations. Had I been able to read these, I would undoubtedly have had a different view of this comic.

In recent months, thanks to Fantagraphics’ wonderful work publishing of Foster’s Prince Valiant in oversized book form, I have been able to enter into the world of Foster’s original comics. Like millions of readers before me, I have been treated to chivalric tales of the good and gallant, the villainous and the vile. While these stories are highly imaginative and take place in a time long ago, they serve as a constant reminder of the adventure of life.

Like the English Arthurian classic Le Morte d’Arthur, Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant begins, not with the titular character, but with his father. The strip premiered on February 13, 1937, and its story begins after King Aguar has been forced to abdicate the throne of Thule (near present-day Trondheim). He, his family, and a small number of loyalists have been driven out of their native land, and they ultimately settle in a barely inhabitable wetland (or “fen”) in Britain. King Aguar’s young son, Valiant, soon begins exploring the fens, finding more than he bargained for.

Though the comic would later become more grounded, the fens are a sort of liminal space, full of magic and nightmarish monsters. The young boy develops his skills there, hunting and fishing animals, both realistic and fantastical. As he grows, Valiant becomes restless, and he eventually leaves the wetland. He soon ends up in Camelot, where he becomes squire to Sir Gawain, and it is then that the real adventures begin.

Valiant quests across his nation and around the world. He encounters oppressed villages, kindly nobles, corrupt knights, stormy seas, elephants, and even giants while working to act justly no matter where he goes. In time, he is knighted. That is not to say that he is a perfect man—he isn’t—but Val (as he is often called) genuinely tries to live up to the expectations of chivalry.

As indicated earlier, Prince Valiant’s style and structure are quite different from those of most comics. Inspired by medieval tapestries, each week’s strip consists of illustrations accompanied by text at the bottom of the image that describes the action and dialogue. When collected into Fantagraphics’ (phenomenally remastered) volumes, the comic has the feeling almost of a beautifully illustrated picture book, but one whose story continues for thousands of pages.

Prince Valiant has long posed a challenge to publishers wishing to bring it to readers. When the strip began in 1937, most people thought comics were such a low art that there was no reason to keep any kind of archive. Thankfully, by the time Foster passed away, this had changed. He was able to gift Syracuse University with his own personal Prince Valiant ‘proofs,’ ensuring that a project like Fantagraphics’ could someday materialize. This doesn’t mean releasing them has been easy; it takes years for the team working on the strips to make the art in each book as pristine as possible.

Even more difficult is the sheer size of the original comics. For most of the strip’s first 40 years, each week’s installment took up a full newspaper page, making full-size reprints unrealistic. Fantagraphics’ recent hardcover editions slightly reduce the size of the art. Measuring 10.5 by 14 inches, these hardcovers maintain the beauty of Foster’s illustrations while still keeping the books small enough that, though large, they aren’t cumbersome to read. The Fantagraphics set is sold in individual volumes and box sets. Each volume has two years’ worth of strips, and each box set has three volumes. Thus, if you pick up the first box set (either for yourself or, as I hope some readers will do, for a young person in your life with a sense of adventure), you’re getting the first six years of Prince Valiant.

Despite how unusual it has always been on the comics’ pages, Prince Valiant is not sui generis; the comic is reminiscent of various artists that helped form its author’s imagination. In his excellent biography, Brian M. Kane identifies Foster’s earliest influences as not cartoonists but painters and illustrators. Looking at E.A. Abbey’s paintings of Shakespearean scenes or the coronation of Edward VII, there is a sense of romance and elegance that makes its way into Prince Valiant. Similarly, though his action scenes are far less dynamic than Foster’s would later be, Howard Pyle’s illustrations of King Arthur and his knights boast detail and perspective that the younger man’s work would echo. Arthur Rackham’s influence can be felt in many of Prince Valiant’s foes, and while much could be said of Maxfield Parrish’s impact on Foster’s work, I see it most strongly in the backdrops of the latter’s adventure stories. Foster also learned from J.C. Leyendecker, James Montgomery Flagg, and N.C. Wyeth, all of whom he encountered at an early age.

But influences do not a masterpiece make. And make no mistake: Prince Valiant is a masterpiece. (As the Duke of Windsor, Edward VIII—a great admirer of Foster’s work—put it, Prince Valiant was the “greatest contribution to English literature in the past hundred years.”) Foster’s work went well beyond his influences. But before examining the comic further, it’s worth looking at the life of the man behind it.

Harold “Hal” R. Foster was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1892. Foster’s early life was full of adventures that could have been in an adventure novel. Despite his father narrowly escaping death in a shipwreck, Hal loved the sea as a boy (something that would be apparent in his depictions of it in Prince Valiant). After his formal education ended at the age of 13, his family moved to Winnipeg, and Hal learned to fish. They were far from well-off, so Hal used his skills in fishing and hunting to help provide for them.

Despite his early intentions to make his living as a boxer, Foster had an appreciation for art from a young age. He taught himself to draw the human form by standing naked in front of the mirror and sketching himself. However, the Canadian winters were so harsh and the heating in the house was so insufficient that he had to learn to draw very quickly. This was part of what enabled him to draw such detailed scenes with many characters, particularly in battle.

As a young man, he began documenting his adventures via drawings, many of which survive today, but his beginning as a professional illustrator was for a company that made very frilly women’s undergarments. Catalogs needed to be extremely accurate to ensure customers’ received precisely what they were expecting, so Foster was expected to get every stitch right. Odd though this early experience was, its ripples can be seen across his career; in later years, Prince Valiant’s medieval world would be characterized by beautifully-rendered (and believable) clothing and weapons that make its Arthurian world feel lived-in.

Foster’s work is romantic in the broadest sense, depicting knights on great quests, but it is also more conventionally romantic, something that mirrored his own life. Foster’s life was, he would be the first to say, a love story. As a young man, he quickly fell in love after meeting a young lady named Helen, and they would later wed. By all accounts, Foster was a very devoted husband, often showing his affection via small gestures and drawings that continued over the decades. This was mirrored in Prince Valiant, for, though not all the marriages in it are as happy as Foster’s own, there is a certain fairytale quality running through some of them, not least that of the courtship of the protagonist Valiant and his love Aleta.

Though chivalric quests may feel a bit abstract to us today, Foster’s own life held examples of these too. My favorite example is that he once rode his bike from Winnipeg to Chicago in 1919 to get a sense of whether he would be able to find work there. This sounds like a great feat to most of us even today, but once we realize that his path was mainly made up of unpaved roads, it becomes all the more impressive.

Two years after his initial trip, Foster moved his family to the United States and began working at an engraving company. In his new country, Foster audited several classes at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, further cultivating his understanding of art. He then got a job at an advertising agency in 1925, illustrating promotional material for things as diverse as railroad companies, food, and pianos.

His big break came in 1928, when he secured a position to illustrate a comic adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan. Though initially intended to be a ten-week limited-run comic in a British magazine, readers clamored for more, and it ultimately became a long-running strip published not just in the UK but the U.S. as well. It was astonishingly successful, spawning legions of fans.

Foster’s work on Tarzan drew the attention of William Randolph Hearst (one of the primary inspirations for the protagonist of Citizen Kane). Hearst, a lover and great benefactor of the comic arts, hoped Foster would create a comic for his papers. When Foster presented him with what would become Prince Valiant, Hearst was so impressed that he offered Foster a 50-50 split of any future royalties on the comic, which was almost unheard of. Foster, unsurprisingly, accepted the offer.

Foster made sure to take advantage of the freedom Hearst’s encouragement allowed. As indicated earlier, Val travels all around the world, and Foster enjoyed traveling to any place he intended to include in a comic. These travels allowed Foster to get to know a place well before showing it in the comic, meaning that readers feel like they are standing right alongside Val. One of my favorite of Val’s trips is when he visits the Holy Land (collected in volume 3 of the Fantagraphics’ collection). Though Foster was not an especially religious man, he depicts places like the Via Dolorosa and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre with a certain reverence and respect, taking more pains than usual to identify each. (Readers interested in this aspect of Foster’s work should also be aware of his brief but lovely adaptation of The Song of Bernadette, collected in volume 19.)

While the adventures depicted in the comic are exciting, they would ring hollow if it weren’t for Foster’s attention to the characters undertaking them. Whether original characters like Val and his wife or those Foster ‘inherited’ from other traditions like King Arthur and Merlin, the major figures in the story feel real, and their stories pull readers in. The best example is likely the tale of Val and Aleta’s courtship and marriage, but even Foster’s more fantastical tales imbue their characters with a profound humanity.

For instance, in the first volume, there is a memorable story of a town that has apparently been long oppressed by a greedy giant. In time, though, Prince Valiant discovers that the giant is, in fact, a kind but physically monstrous man who has long used his power to protect other ‘monstrous’ people who have faced cruelty because of their appearances. In one particularly striking part of the story, Val sits down with the giant, who is drawn in his full glory and horror, taking up most of the comic page. The giant speaks honestly of his pain, isolation, and desire to protect people. In the giant, Valiant recognizes more of himself than he sees in many so-called nobles.

This kind of human drama is part of what keeps readers coming back to Foster’s Prince Valiant nearly a century after it began. Though each page shows prodigious artistic talent and dedication, the author claimed that the visual beauty of a comic mattered little if the story was no good. He thus labored to make his characters and stories compelling. In doing so, he made a work that reminds readers over and over that you and I are not so unlike these adventurers.

While I have previously written about the value of works that, like Watchmen, deconstruct and critique aspects of heroic stories, there is no denying that the human person has a profound need for traditional tales of heroism and valor. These stories, in addition to providing aesthetic experiences valuable for their own sake, have a distinct moral value. There is something ennobling about seeing people facing steep odds, doing the right thing, and emerging victorious. We live in a time when many feel isolated and powerless. This is something characters in Prince Valiant often experience. Like them, we are thrown into frightening and overwhelming situations over the course of our lives, and, like many of them, we have the choice of how we respond to them.

Foster in no way presents his imagined medieval world as perfect—or even necessarily as a more just society than the modern West. However, he constantly presented examples of characters who strove against injustice, protecting the weak and vulnerable from those who would abuse them. Foster’s work is not a mere morality tale—he said preoccupation with simplistic moralism would have damaged his art—but the noblest characters in Prince Valiant approach life as an adventure, one that makes moral demands on us, and one that we can and must face with the best of ourselves. This is, to my mind, the way we all ought to approach our time on this earth. We may not have lances and swords, but at every turn we are in danger of finding a dragon or a cruel tyrant. Reading Prince Valiant, in addition to being an experience of genuine artistic beauty, is a constant reminder that the human condition need not lead us to degradation, but it can instead call us to be strong, brave, and even valiant.