While Brussels celebrates past successes, the removal of the veto, the erosion of the Single Market, and accelerated enlargement threaten to turn the European project into something very different from what Spain and Portugal signed up to in 1986.

When the International Monetary Fund released its World Economic Outlook update for January 2024, many observers raised eyebrows. The Outlook estimates that the Russian economy outperformed both the United States and Europe in 2023:

The number for the U.S. economy is close to the growth rate we can calculate based on GDP numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. With their preliminary estimate of GDP for the fourth quarter included, the U.S. economy grew by an inflation-adjusted 2.6% in 2023.

Some commentators appear to have problems accepting the strong performance of the Russian economy. In a panel discussion at Al-Jazeera, Erlend Bjortvedt, a Norwegian country risk analyst and sanctions expert, expressed frustration that Western sanctions against Russia have not hurt the economy more than they actually have.

Predicting pending doom and gloom for the Russian economy, Bjortvedt met opposition from Chris Weafer, a strategic business consultant with Russia and Eurasia as his field of expertise. While Bjortvedt tried to pin the strong GDP growth number on military spending, Weafer explained that the growth in the Russian economy is widespread and durable.

In a comments-laden news story on the same IMF report, Radio Free Europe reported (emphasis added):

Russian President Vladimir Putin is ramping up spending this year on defense and splurging on the population ahead of elections in March. Russia’s economy has performed much better than experts forecast following sweeping Western sanctions imposed in 2022 as punishment for its invasion of Ukraine.

The implication here is that the Russian federal government is increasing family-oriented benefits in order to buy voter loyalty for the upcoming election.

I am not going to establish the veracity of either this claim or the points made by Chris Weafer in the aforementioned Al-Jazeera debate. However, it is worth noting that the accusation that the Putin administration is using the public purse to ‘buy’ voter support, cannot be true alongside any suggestion that the same president and his party are rigging elections.

Of more importance is the fact that the January World Economic Outlook is not the first time that the IMF has issued a positive assessment of the Russian Economy. In April last year, the Moscow Times reported:

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) raised its 2023 economic growth forecast for Russia on Tuesday, predicting that deficit-fueled government spending would help counteract the growing costs of its war in Ukraine.

In the next paragraph, the article explains that the IMF’s long-term outlook was pessimistic. By 2027, “the Russian economy would be about 7% smaller” than what pre-war forecasts predicted.

Interestingly, the April 2023 outlook came on the heels of another reversal, where the IMF shifted a negative-growth outlook to a positive one. The April update placed Russia’s full-year GDP growth at an inflation-adjusted 0.7%. The IMF’s just-released World Economic Outlook ups that number significantly to 3.0%.

Before we explore where the Russian economic growth is coming from, it is important to address the elephant-in-the-room question that has been sprawling on social media: can you even trust economic statistics from Russia?

If it came straight out of the Russian federal statistics bureau, it would be understandable that critics raised concerns. However, the numbers discussed here are from the International Monetary Fund, one of the world’s most reputable institutions for economic research and statistics. Just like any other reputable statistics agency, including but not limited to Eurostat, the OECD, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the World Trade Organization, or the United Nations national accounts unit, the IMF uses well-established standards for how data is collected, processed, and analyzed.

As a testament to the discernment of the IMF statisticians, a search in their database for numbers on the Russian economy does not turn up as comprehensive a set of numbers as you can get for more open, Western economies. The missing parts pertain to certain technical methods for calculating real vs. nominal GDP and the level of detail in disaggregated GDP data.

In plain English: the IMF either cannot obtain reliable data below a certain level of aggregation, or they find that the numbers they have are of insufficient quality. At the same time, they find other statistics to be reliable enough to be published alongside similar numbers from Europe and America.

The OECD, a large, independent international research institution in Paris, is also a bit limited in its publication of national accounts for the Russian economy.

This means that statisticians and economists who spend all their days analyzing and evaluating data on economies around the world, generally find Russian statistics to be reliable, but either lack access to sufficiently disaggregated data, or have reservations regarding the quality of some subsets of data. These reservations are good for two reasons:

It is worth noting that in this regard, Russian national accounts are of the same quality as national accounts from Western countries were in the 1970s and—in some cases—the 1980s. We have reliable statistics on the U.S. GDP going back all the way to the 1920s, but the level of detail in those numbers is not nearly as good as it is in contemporary GDP numbers.

Those numbers are perfectly trustworthy. By the same token, Russian GDP statistics, published by reputable international statistics agencies, are perfectly reliable—even when they come with a level of detail comparable to similar statistics from the U.S. or European economies half a century ago.

Furthermore, for reasons that I will return to in a coming article, it is extremely difficult to forge data in the national accounts system; for the time being, I refer again to the panel discussion cited earlier, where Chris Weafer actually makes this point.

But what about the sanctions? Have they worked or not? The IMF numbers would suggest that they have not. Another reason to believe that Russia has withstood the sanctions as successfully as the World Economic Outlook report suggests is that the Russian economy is not that different from other advanced, industrialized economies. A macroeconomic overview, courtesy of national accounts from the UN database, paints the picture of a balanced economy with across-the-board decent growth rates.

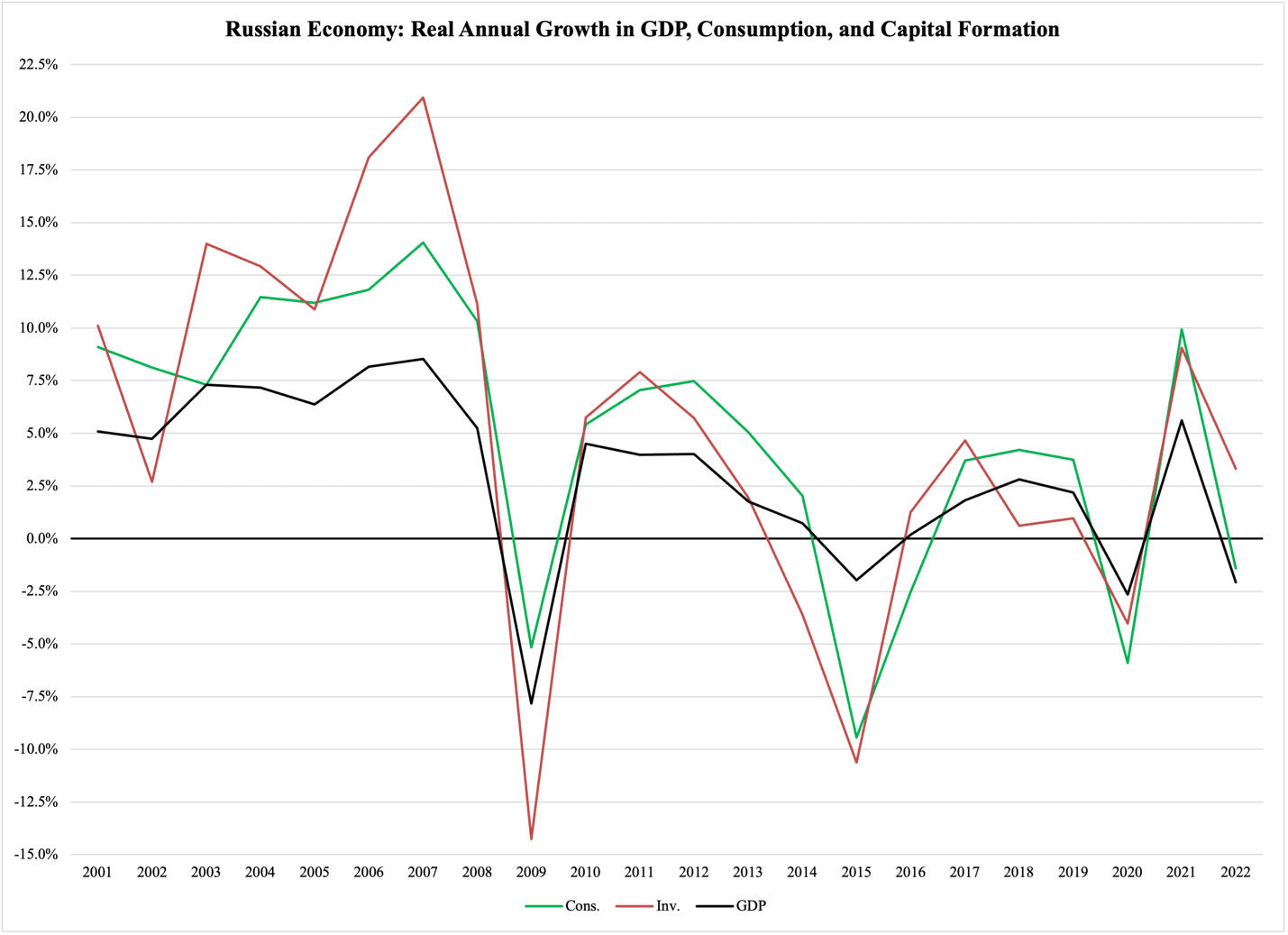

Figure 1 reports the annual, inflation-adjusted growth rates in private consumption and gross fixed capital formation, a.k.a., business investments. The growth rates for Russia’s GDP are thrown in for reference:

Figure 1

The cyclical variations in investments and consumption are exactly what one would expect, with the former preceding the latter. The decline in the overall growth rates from the 2003-2007 growth cycle to the ones in the 2010s is likewise consistent with what one would expect. Or, to be a bit blunt: someone forging GDP data would not think of synchronizing the forged numbers with the international economy.

There are several ways to verify these numbers with secondary data sources; perhaps the best way to do so would be to look at how Russian exports and imports vary with the business cycle. Such variations are easy to establish and compare to how an economy with their trade pattern ‘should’ fluctuate. All foreign trade, like all cross-border financial transactions, can be reciprocated with numbers from the ‘other party’; we know how much oil Europe imported from Russia in any given year, and therefore we know how much they exported.

National accounts can be verified in other ways, which—again—I will discuss in a follow-up article. For now, let us conclude that there is nothing strange about the Russian GDP numbers as published by the IMF. It may annoy us all that Russia seems to have beaten the sanctions, but the fact that they have done it is not a reason to throw dirt at the messenger, i.e., the national accounts numbers.

If we want to reevaluate the sanctions based on effectiveness, then let us reevaluate the sanctions based on their effectiveness.