President of Argentina Javier Milei speaks at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) at the Gaylord National Resort Hotel And Convention Center on February 24, 2024 in National Harbor, Maryland.

Photo: Anna Moneymaker / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / Getty Images via AFP

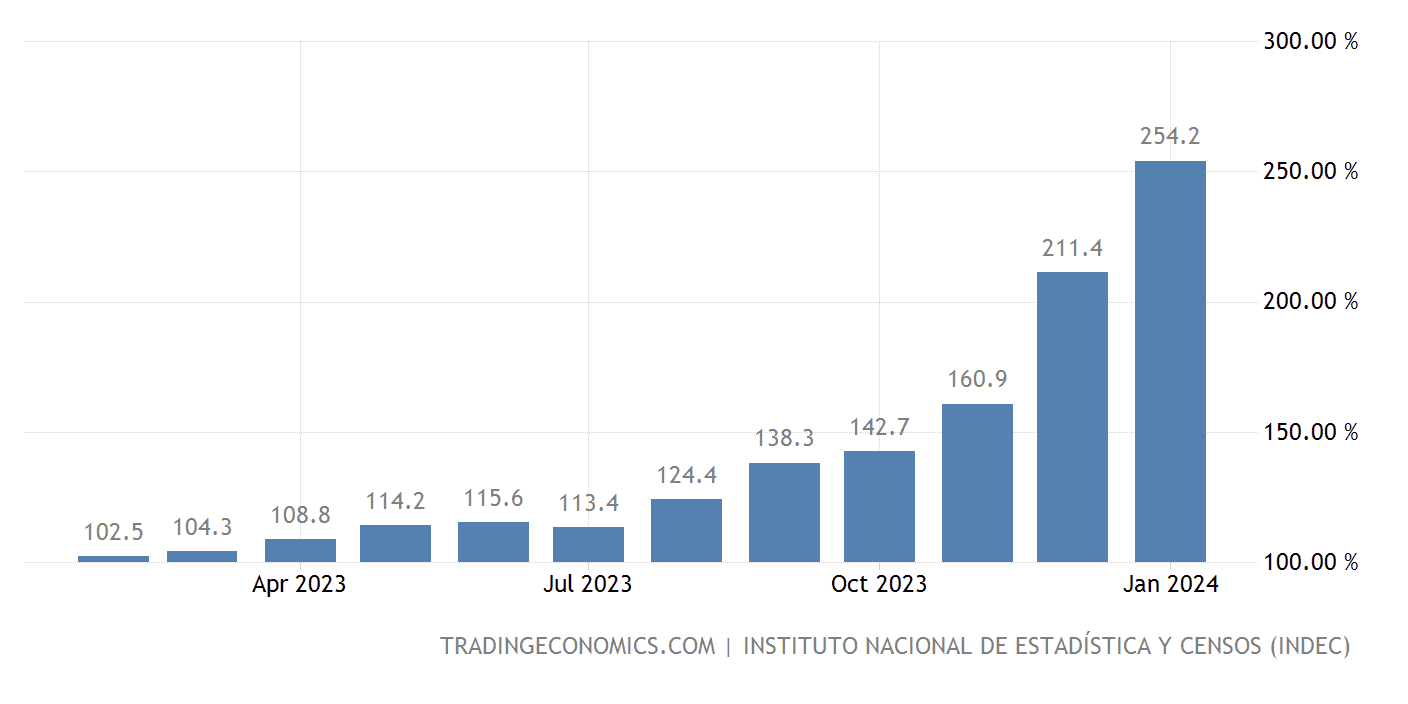

Javier Milei, the new president of Argentina, is wasting no time in the fight for his country’s economic survival. He has good reasons to push forward rapidly: as Figure 1 shows—courtesy of Trading Economics—the Argentinian inflation rate is not only sky-high but accelerating. It just rose past 250% per year:

Figure 1

It is easy to see where this inflation spiral is heading: if inflation continues to rise as it has over the past six months—which is a moderate estimate—the inflation rate will reach 1,000% by this summer. From there, it can easily reach stratospheric levels like those experienced by Venezuela on multiple occasions over the past 20 years.

President Milei has understood two things about this type of runaway inflation: that it is caused by monetary expansion, specifically the monetization of budget deficits; and that it takes extreme, unwavering policy measures to end it. Although it is debatable whether Milei’s proposed anti-inflation methods are the right ones, he leaves nobody in doubt as to what he wants to accomplish. In a recent interview, published on the president’s official Youtube channel, Milei explained:

We would like to move forward with a currency competition system. Go to … primarily a system of currency competition, maintaining the peso and with a law that we will be sending to Congress, which is basically to define seigniorage as … a criminal offense, where basically if the central bank finances the treasury, either directly or through some indirect mechanism, they would end up in jail.

The president uses the term “seigniorage”, which refers to the value that government creates by printing money. His use of the term is not entirely correct. I will return to that point in a separate article; what matters, though, is that from an economic policy viewpoint, his apparent misunderstanding of it does not change the substance of his argument.

Milei does not just want central bankers to face jail time. In addition to the central bank president and its board of directors, he wants to include anyone in the Argentinian congress who votes for a ‘monetized’ budget deficit. Most notably, the nation’s president would also risk jail time, should he sign a budget bill into law with a monetized deficit in it.

Referring to former president Christina Kirchner, Milei calls it the “delirium” of “Kirchnerism” to fill budget gaps with printed money.

Later in the interview, Milei expresses zero tolerance for budget deficits. He wants to use his non-negotiable demand for a balanced government budget as a means to dissuade money printing. Furthermore, as balanced budgets help reduce inflation, GDP growth will increase; higher rates of economic growth bring in more tax revenue, which helps reduce the debt itself.

With lower debt comes lower interest payments on the debt itself. As the budget improves and the debt cost falls, Milei wants to avoid doing “as any other politician would do”—namely spending more money. Instead, he intends to return the proceeds of improved government finances to the people: “by lowering taxes, giving money back to the people.”

This plan to end government borrowing and the monetization of deficits may be drastic, with its proposed jail time for ‘deficit criminals,’ but it is well supported by economic theory. Last year, I co-authored a paper for American Business Review where fellow economist Robert Gmeiner and I established the close connection between, on the one hand, monetary expansion in general and deficit monetization in particular, and, on the other hand, inflation. Reporting the results from five decades’ worth of data, we placed our results in the context of economic theory, showing how our results were not only expectable, but logical from a theoretical viewpoint.

Furthermore, we carefully laid out the chain of events that causes inflation when deficits are funded by the printing of new money. This chain of events is not apparent, even to politicians who make the decision to fund governments with deficits, but once explained in detail—as we do—it shows exactly why the monetization of deficits is so dangerous from an inflationary viewpoint.

Given that President Milei has made the exact right analysis of Argentina’s inflation problem, can he expect to be successful?

If the national congress adopts his bill as he explains it, and if the jail time provision is deterring enough, then he will succeed. He would de facto outlaw monetized deficits—or strictly speaking the act of creating them—which reasonably should deter any law-abiding citizen from doing anything that could be construed as aiding and abetting money printing for the purpose of deficit spending.

The question is what the government in Buenos Aires does when a recession hits the economy and tax revenue falls short of current spending. Like other countries with welfare states that give benefits to people based on their income, Argentina is going to see a rise in demand for those benefits the next time its economy falls into a recession.

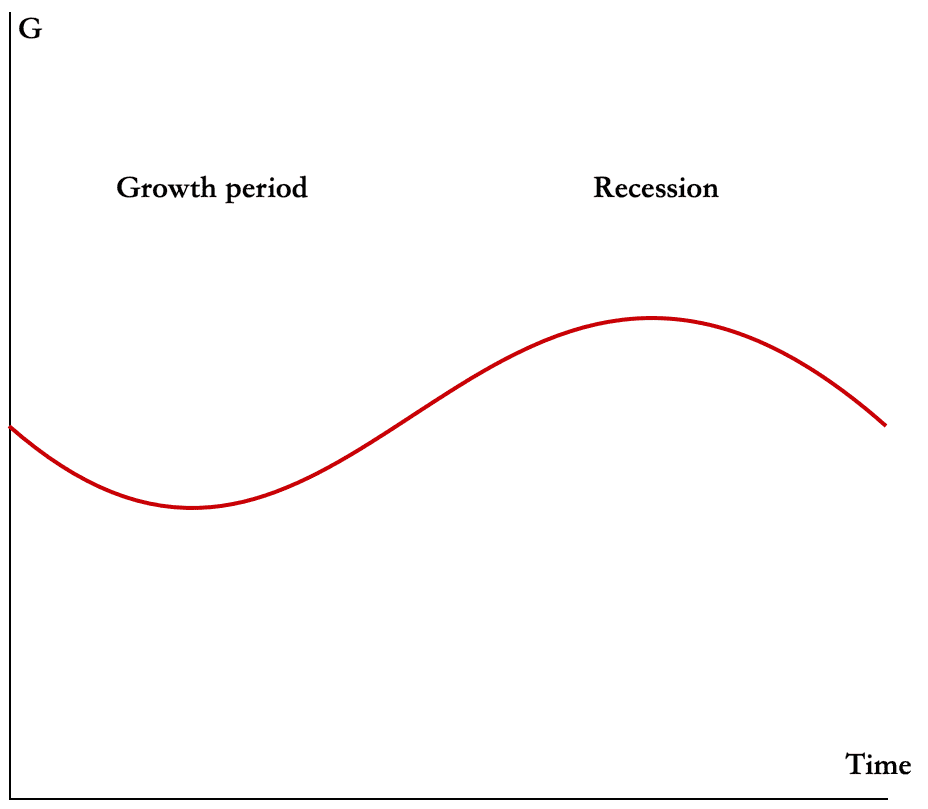

Figure 1 reports in schematic fashion how these welfare-state programs work in terms of spending (G). The red line represents total outlays on benefits for lower-income families. In a growth period when the economy is strong and demand for labor is high, fewer people qualify for low-income support; in a recession, those programs have more takers and therefore cost government more money:

Figure 1

To pay for these entitlement programs, modern welfare states levy high taxes through a complicated tax system. The main characteristic of this system is that

a) its revenue rises with a strong economy; employment is high, which means rising taxable income and more consumer spending subject to VAT and other consumption-based taxes; and

b) its revenue declines in a recession; when people lose their jobs or have to take lower-paying ones, there is a decline in revenue from taxes on income and consumption.

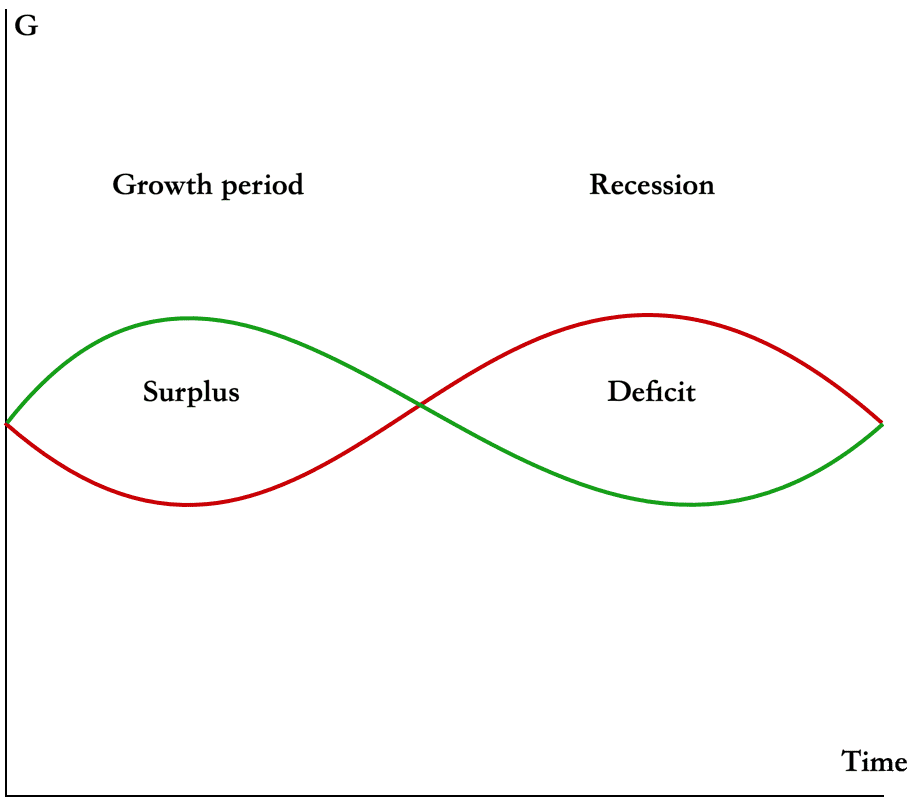

In other words, tax revenue is counter-cyclical to welfare-state spending:

Figure 2

This creates a problem for Argentina’s new president. Outlawing budget deficits altogether would force the national congress to reduce welfare state spending when it is most needed; the only way to avoid it would be to put the budget surplus in the bank and use it to pay for the deficit in the next recession.

For this to work, the Argentinian treasury had better hope that surpluses are big enough to shore up sufficient cash for the next recession. Assuming, again, that deficits of all kinds are made illegal, this is a dicey proposition.

Fortunately, this is not what President Milei is proposing. He has his eyes set on monetized deficits, i.e., the budget shortfalls that are funded by the sales of treasury securities to the central bank. If the treasury can sell its securities on the global market for sovereign debt, then it can still borrow money in a recession—and the people over at the central bank can breathe easily again, knowing they will not be going to jail after all.

By not including all deficits in his criminalization bid, President Milei allows the Argentinian government a small room for fiscal flexibility.

Will this work? Chances are it won’t. The fiscal forces at work in a welfare state’s budget are too strong to be contained simply by a law banning monetized deficits. That does not mean Milei’s initiative is pointless—on the contrary, it is likely going to have precisely the effect on inflation that he seeks. But if he is as serious about zero budget deficits as he is about eradicating inflation, he will have to do more.

A coming article will go into greater detail on what this means.