After the fiscal handwringing in Germany over tough budget priorities, the time has come for France to face the reality of a recession. While President Macron insists on sending €3 billion to Ukraine this year, Vie Publique reports that his government has been forced into painful budget cuts:

In the presentation of the finance bill for 2024, the government expected [GDP] growth of 1.4%. The estimate is lowered to 1%. In order to maintain the objective of reducing the public deficit to 4.4% of gross domestic product (GDP), the government has just published a decree canceling 10 billion euros of credits.

Macron should rethink France’s support for Ukraine, because the €10 billion in budget cuts are only the beginning. The French economy is in poor shape and the outlook is even worse.

To start with GDP growth, the number mentioned by Vie Publique is on the optimistic side. A more likely scenario of 2024 is negative growth, i.e., that the economy is shrinking when the numbers have been adjusted for inflation.

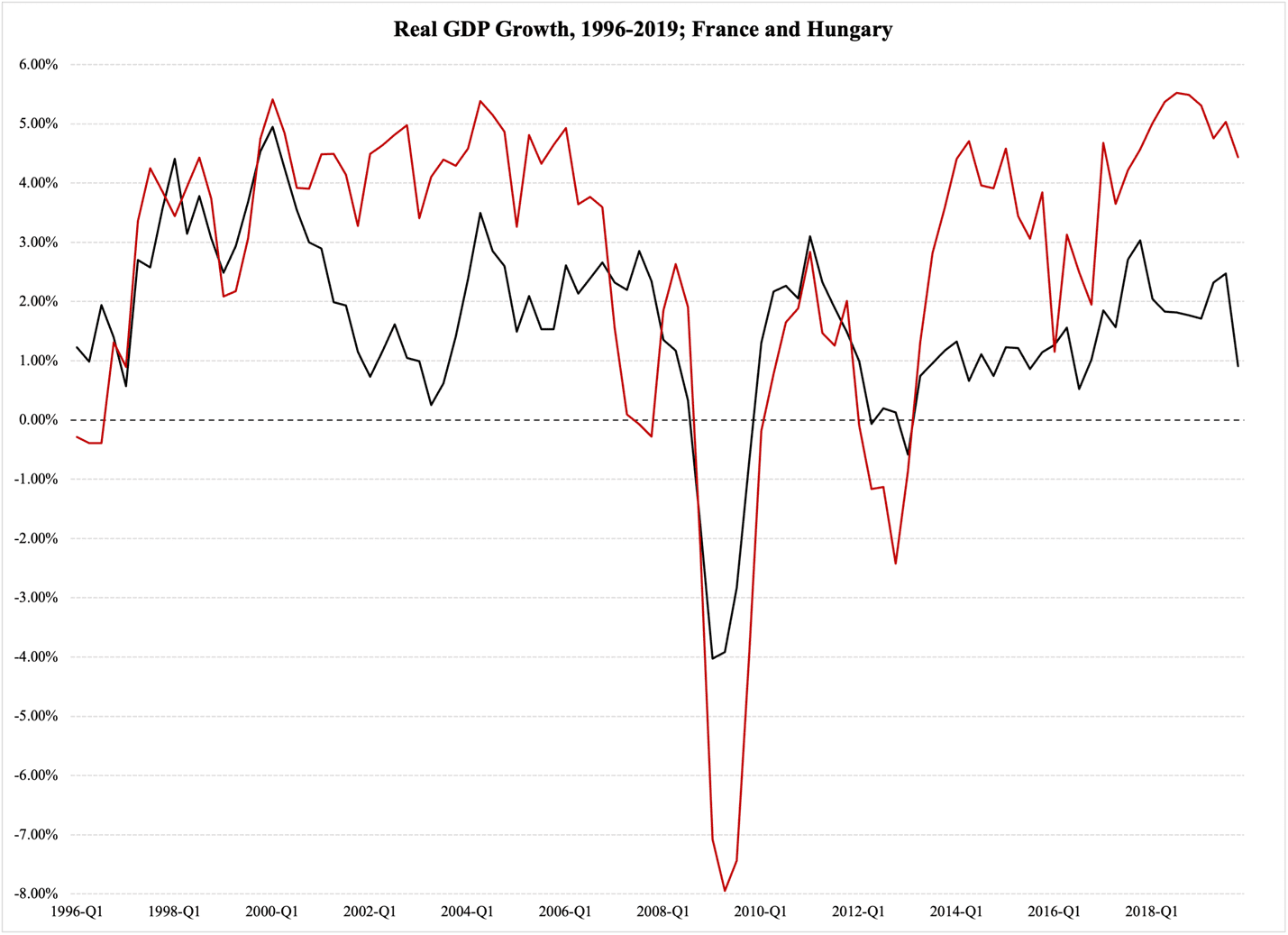

France has been plagued by slow economic growth for decades. Figure 1 reports the real annual growth rates for the French economy (black line) as far back as 1996. The same numbers for Hungary are thrown in for comparison (red):

Figure 1

Black for France, Red for Hungary

I will leave it to the French government to imagine how much bigger their tax base would have been if their economy had grown at ‘Hungarian’ rates since 1996. On average, in the 2000s and 2010s, French GDP expanded by a paltry 1.4-1.5% annually. Over the same period of time, Hungary’s economy grew by 2.6% per year on average.

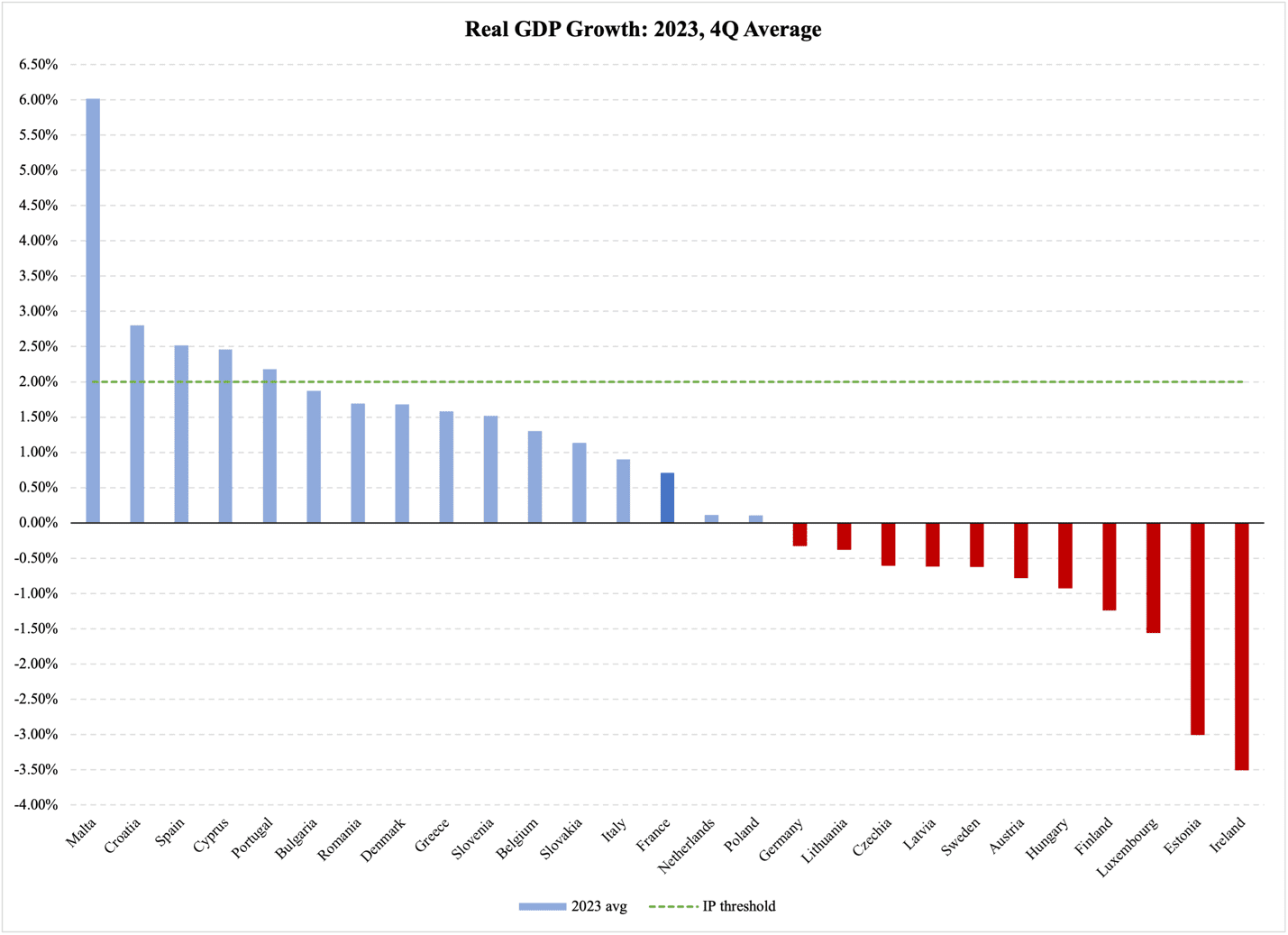

Figure 1 ends in 2019, just before the 2020 pandemic. In other words, it is a good image of a structural weakness that plagues the French economy, but it is also important to remember that this weakness did not go away with the pandemic. If anything, it became more entrenched. Figure 2 gives us the real GDP growth rate for 2023 in the European Union. While 16 countries saw their economies grow last year, 11 EU member states experienced a shrinking economy. France was in the “growth” group, but as the darker blue column shows, it was by no means a spectacular performance. With 0.7% in annual GDP growth, the French government would face a rapid loss of tax revenue in 2024:

Figure 2

The dashed green line represents the 2% growth threshold that keeps an economy evolving; when GDP expands at a lower rate over an extended period of time—not just one year as in Figure 2—the economy becomes stagnant. It ceases to evolve and becomes, in a manner of speaking, frozen in time. For a comprehensive analysis of this phenomenon, see my book Industrial Poverty (Gower, 2014), especially ch. 3.

A recession does not in itself lead to permanent economic stagnation, but it could be the precursor to a period of virtual economic standstill. This makes France’s current situation all the more precarious: most of Europe is moving into an economic downturn, which means that France is going to have a worse economic performance in 2024 than it did in 2023. Expect a shrinking GDP this year, in real terms.

The last point is important. Although there is a correlation between economic growth and the growth trajectory of tax revenue, the latter depends on current-price GDP, not the inflation-adjusted number we see here. Simply put: if we want to know what tax-generating GDP looks like, we add inflation to the growth rate reported in Figures 1 and 2.

If, e.g., the French economy shrinks by 1% in 2024 and inflation is 3%, this means that GDP at current prices grows by 2%. This makes it likely that tax revenue will grow as well; the exact correlation between the two variables depends on, among other things, the progressivity of income taxes and the shares of consumption and income taxes of total revenue.

With its five tax brackets on personal income, France has a predisposition for more fluctuations in its tax revenue than its GDP. In other words, for every 1% rise (fall) in current-price GDP, tax revenue will rise (fall) by more than 1%. This also means that if the trend in GDP is weakening, the trend in tax revenue will be weakening faster. For 2024, this could mean a sudden, and for the French legislature unexpected, loss of revenue.

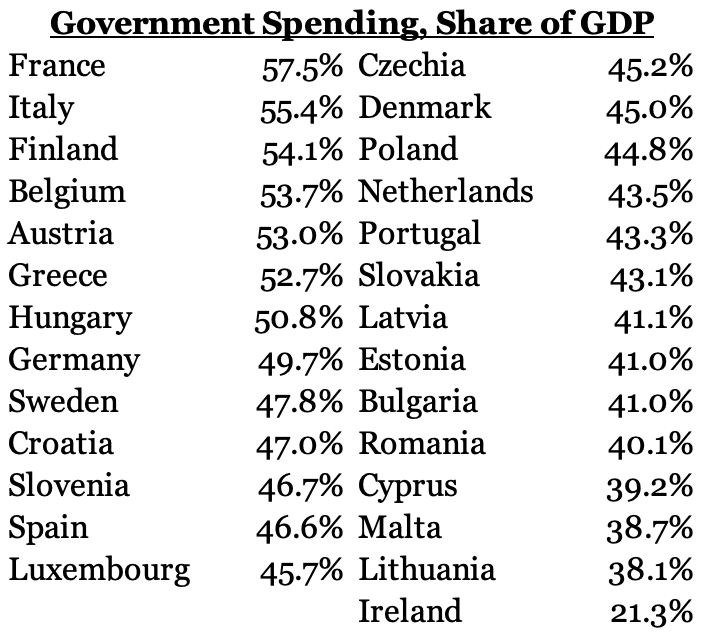

At the other end of the budget, namely on the spending side, France has a problem with far too much spending. Table 1 reports the share of consolidated government spending to GDP in 2021:

Table 1

The higher the share of GDP that the government uses, the slower the economy grows. There is a statistically clear but as of yet theoretically not fully explained threshold at 40% of GDP in government spending. When an economy reaches this point, it can expect permanently slower GDP growth, almost always below 2% of GDP.

As Table 1 shows, 23 of the EU’s 27 member states were above this threshold last year. France leads the pack, with government taxing away and distributing 57.5% of GDP. This sheer size of government is enough to suppress economic growth, and thereby tax revenue, in two ways:

As if all this was not enough, France runs the risk of an accelerated economic downturn. All it takes is for the Macron government to start slashing spending while trying to raise more revenue with new taxes. This is fiscal austerity, which inevitably will lead to a worsening of the recession as people lose more money to taxes and have less to spend.

It remains to be seen if France is going to go down the austerity path or not. But even under the best possible circumstances, the French people are in for a rough economic ride this year.