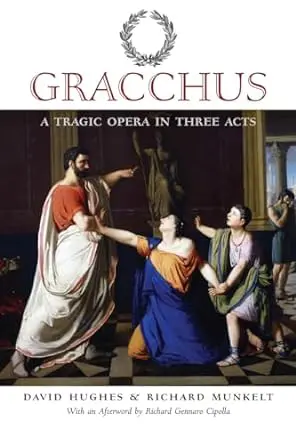

The Death of Gaius Gracchus (1789), an oil on canvas by François Jean-Baptiste Topino-Lebrun (1764-1801), located at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille, Paris

At The Palace Theatre in Stamford, Connecticut, on the 19th of August 2023, our opera, Gracchus, was given its world premiere, before an audience of six hundred. Through the creation and production of the opera, our overarching intention was to make a contribution toward the revival of classical culture, according to the aesthetic theory of the total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). That concept signifies a drama of perennial human themes—of love and suffering, sin and redemption, time and eternity—embracing music, poetry, dance, scenography, and philosophical reflection in a spectacle of emotional power whose purpose is to entertain and to edify. Like Jacob’s contest with the angel, the total work of art wrestles with the human impulse to comprehend, through both the senses and the intellect, the beautiful, and the sublime. On the very point of the sublime, it is hard to imagine any artistic expression ever surpassing Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, except for the religious drama on which it was based, the archetype of drama, as Mallarmé thought of it.

This aesthetic sentiment, accompanied by an anthropology and theory of action, negotiates the divide between antiquity and modernity in terms of heteronomy and autonomy. Pre-Enlightenment man saw himself as constrained by moral precepts, whose foundation was outside and above himself (heteronomy). In contrast, modernity limits its purview to two kinds of law: human (or positive) law and the laws of a non-purposive natural science. The former gave birth to drama drawn out of the conflict of man with himself and with society in relation to the demands of a divine order. But the latter state of affairs, in positing that man was free only if he gave law to himself (autonomy), limits humanity to physical transactions, replacing the human drama with social mechanics of clashing appetites and interests. This would appear to fall rather short of the spiritual horizon of our race. To be sure, the ancient world had its faults. The outstanding failure of ancient civilization was the institution of chattel slavery. But ironically, the ancients also bequeathed an ethical perspective in the form of the natural moral law, carried over into Christianity, that could be, and was, employed to condemn that institution. Conversely moderns, with their inexorable slide into relativism, are theoretically defenseless against Nietzsche’s ‘new slavery.’

Foremost in the ancient mind (right up through the Renaissance) were the hierarchical degrees of existence and the analogy of being through the idea of the person. There were mortals and immortals. What linked them was personhood. In this regard, Homer and St. Paul shared the same frame of mind. “I kneel before the Father from whom all fatherhood in heaven and on earth is named,” stated the Apostle. Where worlds correspond, metaphor, parable, and symbol achieve a supreme cognitive status. Hence, the poetic enterprise of grasping the whole is best served, we believe, through the living art of the total music drama, for it holds out the prospect of joining logos and mythos into a single worldview that will satisfy the mind and the heart.

The traditional arts do not flourish in our times, either as objects of esteem or of imitation; an imitation, we hasten to add, that ought at all times to be reverent without being slavish (e.g., the Beaux-Arts style). The skills for such imitation are nowadays rare because they do not fit in with the latest educational fashions. As progress has become associated with technical innovation, febrile consumption, and relentless digital waves of the topical and trivial, the current Western appreciation of the classical artistic vision has generally withered to the point of oblivion. Today, among the gatekeepers of culture, the performance of old school art is more an occasion for virtuosity than of cultural education; for the gatekeepers themselves, in many cases, have lost a personal connection with the original inspiration (mostly of a religious nature) and social significance of the traditional arts.

Nevertheless, through the millennia, from Gilgamesh to Shakespeare, but not excluding the noteworthy artistic achievements of the more recent past (think of Melville and Messiaen), the traditional arts have been incomparable for their vivid and penetrating exploration of the character of man and his odyssey. On the other hand, 21st century secular dreams of interplanetary colonization, terraforming Mars along the way, must appear not a little ridiculous when we hardly know ourselves anymore and cannot even cure the ills of earthly life. Moreover, how can we answer momentous present-day questions, for example, of gene editing or the right use of A.I., when we have lost acquaintance with the springs of high culture (not to mention the folk genius of immemorial custom and crafts), and the history of ethical inquiry? Doubtless, wherever we may go, fallen human nature will follow, as the nefas that infects man’s heart and for which there is no natural remedy. In any case, the grandest dramas reveal the emotional storms and recondite longings of the human spirit, while holding a mirror up to the moral fabric of the universe. Their art is both cathartic and therapeutic; their endeavor is the endeavor of Gracchus.

Though set in ancient Rome in the year 121 B.C., a year that convulsed the Roman Republic and augured its decline, our opera uses the veil of times gone by to speak to our own. At work in Gracchus, therefore, is both a political allegory and a religious commentary vis-à-vis western civilization as we find it today. Political doctrine of one sort or another has been a ubiquitous feature of opera from the beginning, starting with Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo; likewise religion, the soul of culture. The mixture of pagan and Christian motifs in Gracchus, as well as the dramatic use of different art forms, descends from both Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata and its subsequent operatic incarnation, namely the remarkable Armide of Gluck, so admired by Wagner. Of course, the concurrence of pagan and Christian facets in works of fiction go back to Beowulf and forward to The Lord of the Rings, and can be found in other European literary traditions of a medieval provenance.

Our opera is animated by the story of Gaius Gracchus, its eponymous hero, as told by Plutarch in his famous Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. However, we tell a fictionalized version of Gracchus’s life in order to meet certain dramatic needs and to highlight some universal human concerns and values. The historical Gaius Gracchus had a notable and much older brother, Tiberius, as well as a renowned patrician mother, Cornelia, the daughter of Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal, the archenemy of Rome. Gaius and Tiberius were Tribunes of the Plebs. In an effort to stem the tide of oligarchy, both were assassinated, some years apart, for their zealous promotion of various reforms of the Roman polity that resembled the political agenda of populism. Of the two brothers, Gaius Gracchus was reputed as the greater orator and more ambitious. Nonetheless, our drama brings Tiberius Gracchus to the stage as a ghost who exhorts his younger brother to complete the work of reform, which he, Tiberius, had started, and for which he met with a violent end. It contains a historical introduction for those who wish to understand something more about the late Roman Republic in which the Gracchi lived.

Gracchus is a grand opera in three acts, with nine soloists, choruses, and dancers. There is, for modern opera, a relatively strict division between recitative and aria; the former, as per convention, advances the dramatic action, while the latter allows characters time to pause and reflect, either to themselves or to one another, on their emotional and spiritual states. Choruses (principally to set the scene) and ballets (to provide a parallel in movement to developments in plot) round out the score. What is provided in the print publication is, of course, the libretto and not the musical notation. However, we give along the way brief descriptions of the music which animates each scene. As with any opera, music is the most characteristic element of our work. It is its signature and the key to the whole, unlocking the meaning of each part and integrating all in an artistic unity. Music is no accidental add-on to the story, but the organic form of the libretto, its principle of life, as it were. No other art form has quite the energy to lift the soul above the mundane, above the phenomenal into the realm of the Spirit, precisely because all was originally suffused with ratios and cosmic attunement, the harmonies and dissonances within man himself being the marrow of dramatic works of art. If one can understand man, one can understand the spheres and all—a true theory of everything. Thus, in keeping with the appeal of the sublime, the music of Gracchus strives to soar, and reaches new heights at its climax. We ardently hope, therefore, that more people will directly experience Gracchus’s unique score in future productions.

Finally, a few thoughts on tragedy. Gracchus is a tragic opera. In contrast with comedy, tragedy typically means a drama with a dark and unhappy ending, consisting principally in the death of a noble protagonist after his rise and fall. That fall is often the result of an overreach, a certain destiny (accepted or not), a blindness to personal flaws, or a misconstrual of the celestial will. These dramatic elements, in one form or another, are true of our opera. But there is also a strain in classical tragedy, from which Gracchus attempts to learn, that culminates in a touch of hope—the indication of some higher and righteous power at work, or an expression of a metaphysical insight into the true measure of human actions. None of this diminishes the pain and suffering of the tragic experience, any more than did the prescience of the Resurrection mitigate the actual terrors of the Passion. In other words, tragedy foreshadows comedy if only to return again, until the wheel and ordeal of life end in the life to come—where, for the just, there is only and forever the heavenly comedy of love fulfilled.

Classical tragedy thus avoids nihilism. The old tragedians thought their art ought to be majestic and sobering. Given here and there to the depiction of violent forces, even to the ghastly, it was never ghastly for horror’s sake, which is to say that it was never about pointless suffering. The old tragedy does not succumb to the hopelessness and alienation that eat at the root of the psyche in so many a modern and post-modern thinker. The words of Bernard Williams in Shame and Necessity are, at present, paradigmatic: “We know that the world was not made for us, or we for the world, that our history tells no purposive story, and that there is no position outside the world or outside history from which we might hope to authenticate our activities.” We do not share Williams’s grim outlook, but instead affirm its opposite in light of the transhistorical aspiration for Being and the Good, which is at the core of the culture of humanitas. Humanity stands for no hologram or simulation, no machine or algorithm, but rather for creatures endowed with real intelligence, free will, and emotion, creatures made of flesh and blood, not wires.

Accordingly, whatever the merits of its score, and the powerful evocation of psychological torment that can indeed afflict us, we must finally part company with the ‘Night’ that keeps its grip on Alban Berg’s Wozzeck until the finale. If we cannot follow Berg, however, our classical sensibilities also will not allow us to indulge Pietro Mascagni’s Iris, with its floral apotheosis of unremitting victimhood, even as the splendor of the ‘Inno al Sole’ must prove agreeable. More accurately, the sensibilities behind Gracchus incline to a reconciliation of classicism (noble actions) and romanticism (inner tension and feelings), while sympathetic to the art of symbolism and suspicious of naturalism. Like the symbolists, dear to us is the conception of ideal beauty, a beauty that can be glimpsed in the most extraordinary works of art such as the serene countenance of the Athena Lemnia or in the Titian Assumption.

The tragic strain that is our teacher and guide is constitutive of various epic tales that have nourished the operatic imagination. The Oresteia is rounded with the transformation of the Furies into the Eumenides; the self-blinded Oedipus sees what we cannot and so experiences the mystery at Colonus, while intrepid Antigone is victorious in death; Euripides almost bursts the bounds of tragedy with the dissuasion of Heracles from suicide; beyond some of Seneca’s monstrous figures is the tribunal of providence or of nature; Hamlet attests a special providence in the fall of a sparrow and is succeeded by Fortinbras, who has the prince’s ‘dying voice,’ and the miserable Lear ends his days by looking excitedly upon, or through, the lips of restoration. As if addressing this strain, but in another type of drama, that of the history play, Henry V, the Bard confides a secret of human affairs: there is a little touch of Harry in the night. Gracchus and its conclusion represent a musical offering on the altar of this great dramatic tradition.

Rev. Richard Munkelt was born in Connecticut and has lived in Japan, Manhattan, and Italy. He is a graduate of Kenyon College, the New School for Social Research, and the University St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome. Fr. Munkelt holds a doctorate in philosophy. His dissertation was on the metaphysical foundations of modern logic in the work of W.V. Quine. This in turn became the basis of his magnum opus, Metaphysics and Modernity, From Parmenides to Quantum Physics, published in the fall of 2023. But over the years in the midst of his philosophical researches and pastoral work, Fr. Munkelt dreamt of writing a story of operatic proportions. When reading Plutarch’s Life of Gaius Gracchus, he found just what he needed to realize his dream. Hence, the opera Gracchus, a tale of an ancient tragic figure and an allegory of our times, fruit of a long collaboration with the composer, David Hughes. Fr. Munkelt lives in New Jersey and celebrates the Traditional Latin Mass.

David Hughes is organist & choirmaster at Saint Patrick Oratory in Waterbury, Connecticut, where he directs the St. Patrick Choir and the St. Elijah Choir, a new ensemble of Catholic students at the University of Connecticut. He directs Viri Galilæi, an ensemble of men from the tristate New York. A board member of the Church Music Association of America, Hughes serves on the faculty of its annual Sacred Music Colloquium. He is director of music for the Roman Forum’s annual two-week Summer Symposium at Lake Garda in Italy; he is also a board Member of the Roman Forum. He was named chant instructor for St. Benedict Abbey in Still River, Massachusetts. He has traveled frequently to give workshops, clinics, and recitals in North America, South America, and Europe.