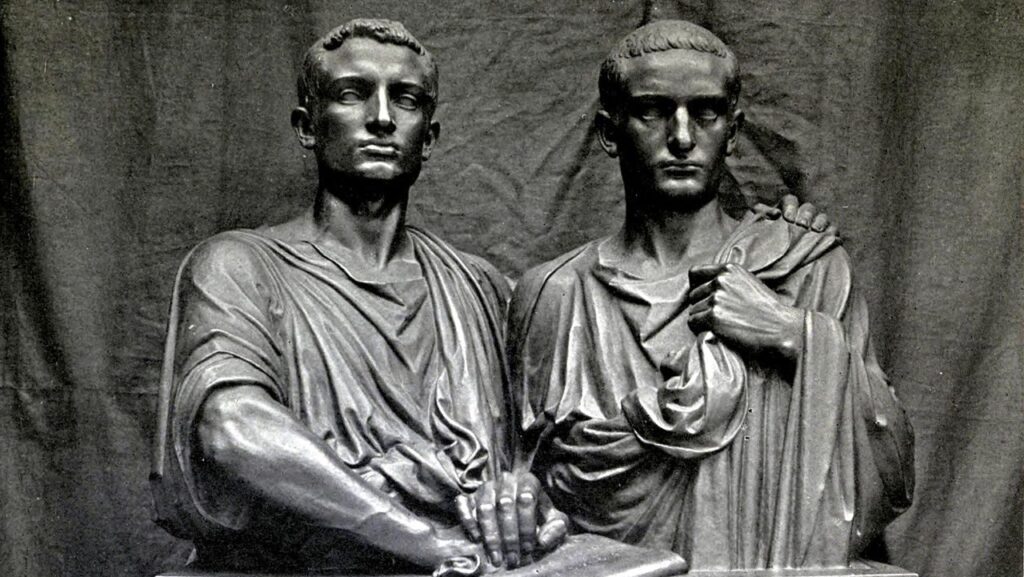

The Gracchi, a sculpture by Jean-Baptiste Claude Eugène Guillaume (1822–1905), located at Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The document the two brothers hold in their right hand bears the inscription “property”.

If a visionary were to descend the way of the Trojan Aeneas, down into the land of the dead and past it, unto the Elysian fields where Virgil locates his starry images of archetypal history—if such a one were to enter into the symbolic annals of Rome, its armouries of mythical weapons, and libraries of sacred texts—he would find the shield and lance forged by Vulcan in Sicilian magma, the Fascinus of the Vestal temple, the philosophical and legal tomes of wise Numa Pompilius, said to have been found in his grave in lieu of that king’s corpse.

And next to these, perhaps to his surprise, he would also see the unassuming war-ledger of one Tiberius Gracchus, which this future tribune of the people took back to Rome with him after a foreign campaign not destined to be remembered as a victory.

But why should so unexceptional a document sit in such exalted company?

Because it represents the true Rome—the Rome of philosopher-king Numa, so opposed to aggressive war; of imperium as ecumene, not imperialism.

The war-ledger in question was retrieved on account of Tiberius’s friendship with the Iberian Numantines, with whom Rome was at war.

Writes Plutarch (Parallel Lives, Tiberius Gracchus, VI):

All the property captured in the camp was retained by the Numantines and treated as plunder. Among this [Sic] were also the ledgers of Tiberius, containing written accounts of his official expenses as quaestor. These he was very anxious to recover, and so, when the army was already well on its way, [he] turned back towards [Numantia]. … After summoning forth the magistrates of Numantia, he asked them to bring him his tablets, that he might not give his enemies [back in Rome] opportunity to malign him by not being able to give an account of his administration. The Numantines, accordingly, delighted at the chance to do him a favour, invited him to enter the city; and as he stood deliberating the matter, they drew near and clasped his hands, and fervently entreated him no longer to regard them as enemies, but to treat and trust them as friends. Tiberius, accordingly, decided to do this.

At this point, a scene deserving of artistic canonization as an emblem of Roman Hispania unfolded—we have a shared meal, frankincense, and the tribune’s records, items of Biblical resonance:

In the first place, the Numantines set out a meal for him and entreated him by all means to sit down and eat something in their company; next, they gave him back his tablets, and urged him to take whatever he wanted of the rest of his property. He took nothing, however, except the frankincense, which he was wont to use in the public sacrifices, and after bidding them farewell with every expression of friendship, departed.

Tiberius negotiated a second peace treaty with Numantia, which, though rejected by the Roman Senate, would, many centuries later, resonate with Miguel de Cervantes, who imagined what Rome ought to have been: a civilizational project, dispensing with imperialistic predation [italics mine]:

Numantia, of which I am a citizen, illustrious general, sends me … to request your friendship. It was a stubborn and cruel persistence over many years that caused Numantia’s troubles, as well as your own. Our city would never have departed from the law and privileges given her by the Roman Senate if not for the torpid command and outrages committed by one consul after another. With unjust statutes and avarice, these did put so heavy a yoke on our necks that we were left with no choice but to drive them off.

—Day One, Siege of Numantia

Tiberius Gracchus, along with figures like Cincinnatus, represents a Rome consonant with medieval Christendom’s decentralisation and communality.

Cervantes’s ideal of local autonomy, together with participation and integration in imperial civilization, is precisely the arrangement that Tiberius attempted to bring about. The compatibility of imperial and indigenous imperatives—the universal and the local—also comes through in that initiative for which Tiberius is most known, namely his land reforms.

Plutarch tells us that the violation of common land and those provisions that had previously been set aside for the poor resulted in a concentration of property ownership by which the wealthy were able to displace free labourers in an economy in which foreign slaves became ever more prominent:

Of the territory which the Romans won in war from their neighbours, a part they sold and a part they made common land, and assigned it for occupation to the poor and indigent among the citizens, on payment of a small rent into the public treasury. And when the rich began to offer larger rents and drove out the poor, a law was enacted forbidding the holding by one person of more than five hundred acres of land. For a short time, this enactment gave a check to the rapacity of the rich and was of assistance to the poor, who remained in their places on the land which they had rented and occupied the allotment which each had held from the outset. But later on, the neighbouring rich men, by means of fictitious personages, transferred these rentals to themselves and finally held most of the land openly in their own names.

The following passage from Parallel Lives is particularly relevant to the early-modern erasure of common, village land and the current, post-modern economic formula of low birth rates and mass migration:

Then the poor, who had been ejected from their land, no longer showed themselves eager for military service and neglected the bringing up of children, so that soon all Italy was conscious of a dearth of freemen and was filled with gangs of foreign slaves, by whose aid the rich cultivated their estates, from which they had driven away the free citizens. An attempt was therefore made to rectify this evil. … Tiberius … on being elected tribune of the people, took the matter directly in hand.

According to Tiberius’s brother, Gaius, it was when the former was “passing through Tuscany on his way to Numantia” that he “observed the dearth of inhabitants in the country and that those who tilled its soil or tended its flocks there were barbarian slaves, [so that] he then first conceived the public policy” of restoring shared ownership of the land. Plutarch adds that “the energy and ambition of Tiberius were most of all kindled by the people themselves, who posted writings on porticoes, house-walls, and monuments, calling upon him to recover for the poor the public land.” There was, then, a popular call to restore local labour to the countryside and restrain the concentration of land ownership by the wealthy.

In Tiberius, we may see a defender of the rights of indigenous peoples in Iberia, no less than of those of indigenous Italians. He stands as a symbol both for the necessary balance between the universal and particular, the large and the local, grandeur and the pasture, as well as of the relationship—so strikingly relevant to our present situation—between oligarchy, displacement of the native poor, and use of exploited foreign labour.

These twin policies—which won Tiberius the friendship of the foreign Numantines and the affection of his own Roman people (indeed, he was popular in his lifetime, and Plutarch tells us that Scipio Africanus was faced with some abuse when he tried to criticise the by-then-dead Tiberius at an assembly)—are of course intimately related. To oppose a domestic economy that requires cheap (slave) foreign labour is to de-incentivize both the slave-generating military or diplomatic machinery and a foreign policy based on subordination.