When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its inflation data for March, it sent shockwaves through the internet. Yahoo Finance declared inflation “hotter than expected,” U.S. News echoed the same sentiment, while Fox Business opined that

Inflation accelerated for the third straight month, keeping prices painfully high for millions of Americans and likely delaying any interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve.

Not everyone was on board with the worries. According to Courtenay Brown over at Axios, the inflation figures for March “offer room for guarded optimism” and are “signals of disinflationary relief” to come.

Notably, Brown also co-authored a piece with Neil Irwin where, analyzing the very same inflation numbers, they explained:

The latest data, which also show a pick-up in the annual CPI figure, extends a streak of hotter inflation figures than policymakers would like—a key sign that returning inflation to 2% might take longer than anticipated.

With so many different voices, who is right and who is wrong?

To answer this question, we need to move away from words like “anticipated” and “expected.” These are used when commentators use predictions made by analysts in different positions. These predictions almost always turn out to be wrong, which makes for attention-grabbing headlines—especially when, as in this case, reality turned out to be worse than the forecast.

To the generic media consumer, the ‘worse than expected’ headline sounds dramatic, but for those of us who do forecasting on a regular, professional basis, this is barely even worth a yawn. Forecasting of macroeconomic variables is a notoriously inexact science—to use the word generously—and it gets even more dicey when economists dispense predictions of exact numbers. A forecast of inflation at 3.4% is wrong if the actual number turns out to be 3.5%—and it is also wrong if the actual number is 6%.

If economists learned to make ‘Keynesian’ forecasts, the error drama would pretty much go away. British economist John Maynard Keynes famously said of economic forecasting that ‘it is better to be approximately right than exactly wrong.’ It is worth noting that Keynes was schooled in mathematics and especially in probability theory, which laid the foundation for his groundbreaking contributions to economics.

If we see inflation forecasts as approximations, we take focus off the fallacy of the exact number and onto trends in key macroeconomic variables. Viewed this way, the U.S. inflation number for March takes on a very different meaning.

Before we get there, though, let me add a comment about another aspect of media-based inflation commentary: the affinity for the concept of ‘core inflation.’

In one of her pieces for Axios, Courtenay Brown puts a great deal of spotlight on this concept. To get to ‘core’ inflation, you take food and energy out of the standardized, comprehensive inflation measurement we all know as the Consumer Price Index, CPI. Unfortunately for Brown, who, as mentioned, is trying to put a positive spin on the inflation figures, there is still not a downward-enough trend here. Therefore, she resorts to something almost unheard of: a “supercore” inflation figure where the cost of housing (or sheltering) is removed from the services part of CPI.

As Brown rightly points out, housing costs in the U.S. economy have gone up quite a bit during the recent inflation episode. So has energy and food; a recent Fox Business article pointed to auto insurance as a late-coming contribution to inflation. Therefore, simple arithmetic dictates that removing these in any combination from the CPI will produce a lower inflation rate.

It is never a good idea to analyze inflation while disregarding certain parts of the economy. The consumer who has to pay his way through everyday life cannot disregard his mortgage, his heating bill, the gasoline for his car, or his weekly grocery run. Furthermore, once you remove one variable from the CPI, you have to remove the interaction between that variable and all the other variables in the economy.

This is a point that nobody discusses in the inflation debate. Suppose we take out housing costs from the CPI. Looking at March inflation, that means a lower rate, which as mentioned some commentators use as a reason to find encouraging news in the latest inflation figures. However, when we take housing costs out, we implicitly assume that the inflation we see elsewhere in the economy would remain the same if people were able to somehow disregard their housing costs.

If people did not have to worry about housing, they would spend more money elsewhere, including but not limited to food and energy. This in turn would increase demand on those markets—which would increase prices. Hence, inflation would be higher.

In other words: the reason why inflation looks lower once we deduct housing costs is that people have to prioritize housing—as they have to prioritize food and energy—while diverting money away from less essential goods and services. When inflation rises generally in the economy, the diversion of money from less essential spending items eases inflation pressure there; the concentration of spending on essential goods and services contributes to even higher inflation in those markets.

For this reason, it is unwise, not to say naïve, to rely on any kind of ‘core’ inflation measurement to try to understand where inflation is actually heading.

With that said, here are the March figures for two of the three most important inflation indices for the U.S. economy (the third being the GDP deflator, which we will get back to later):

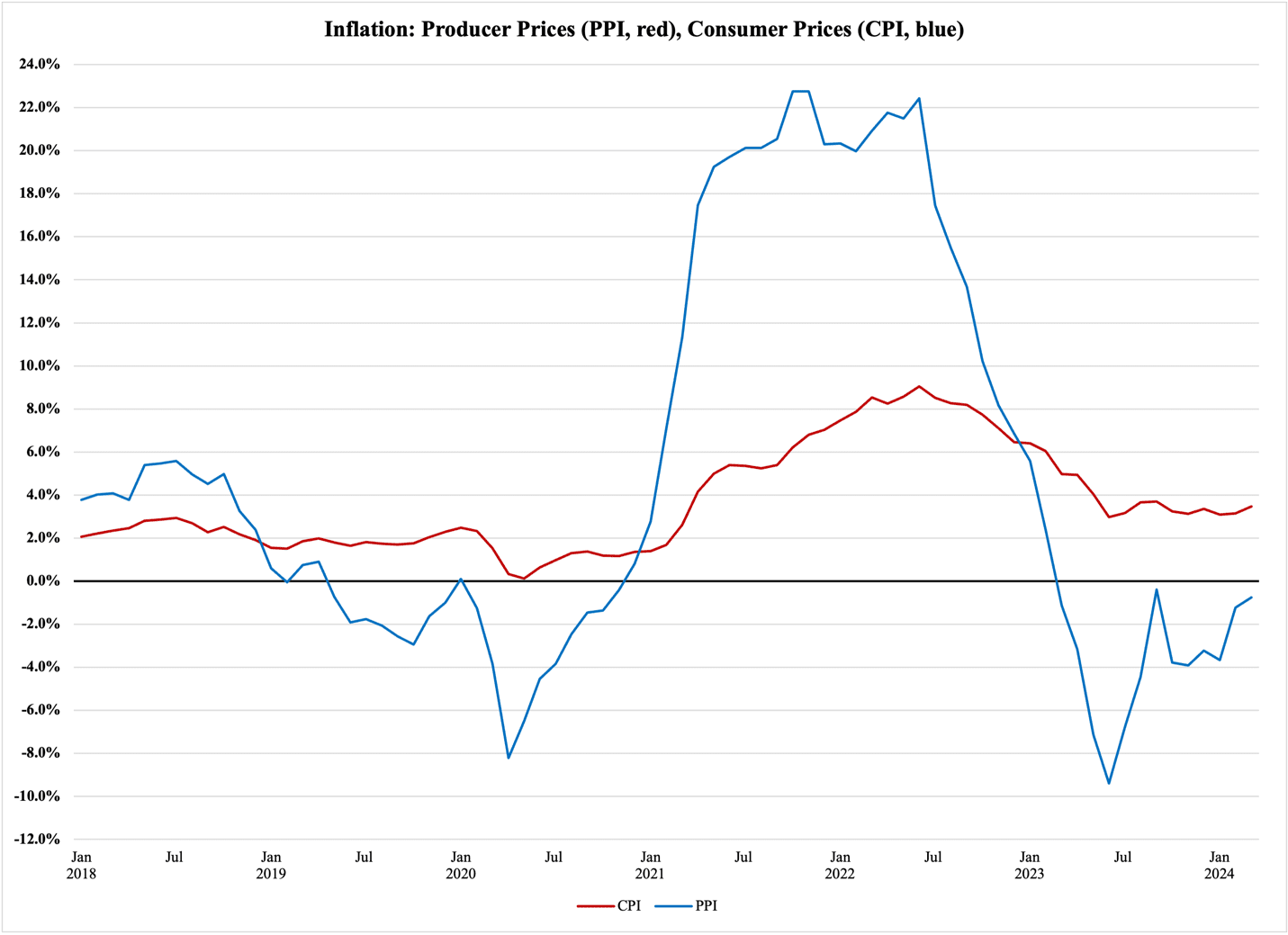

Figure 1 reports these numbers in their recent historical context.

Figure 1

Producer prices are always more volatile than consumer prices. From a causal viewpoint, they lead changes in consumer prices: a change in the PPI is followed by a CPI change two months later. This is not an exact causality—those are only found in natural sciences—but a general, statistically valid rule. This is why the rise in consumer-price inflation (red) in 2021 and early 2022 begins after there is a rise in producer-price inflation (blue). The decline in inflation follows the same causal pattern.

But what do we make of the most recent inflation figures? Over the past ten months, since June last summer when inflation came back down below 4%, consumer prices have increased by notably steady rates in the 3-3.7% range, with a 3.3% average.

Producer prices have been in deflation territory since March last year, with an average of -3.8%. That deflation rate is coming to an end, but that does not mean we will see a spike in CPI inflation. Let us keep in mind that we are talking about annual inflation numbers here: once inflation has been deflation for a year, economic common sense says that we would not want more deflation, as that would indicate there is something substantially wrong with our economy.

To make a trend prediction, I expect PPI inflation to park itself in a modest positive territory with an average in the 1-2% range over the next several months. However, it is important to remember that producer prices are more volatile than consumer prices, which means that there will be occasional, significant deviations from this range.

As for consumer-price inflation, it will remain in the 3-3.5% range for the coming several months. For reasons that require their own article, it is unlikely that CPI inflation will return to the 2% level any time soon.

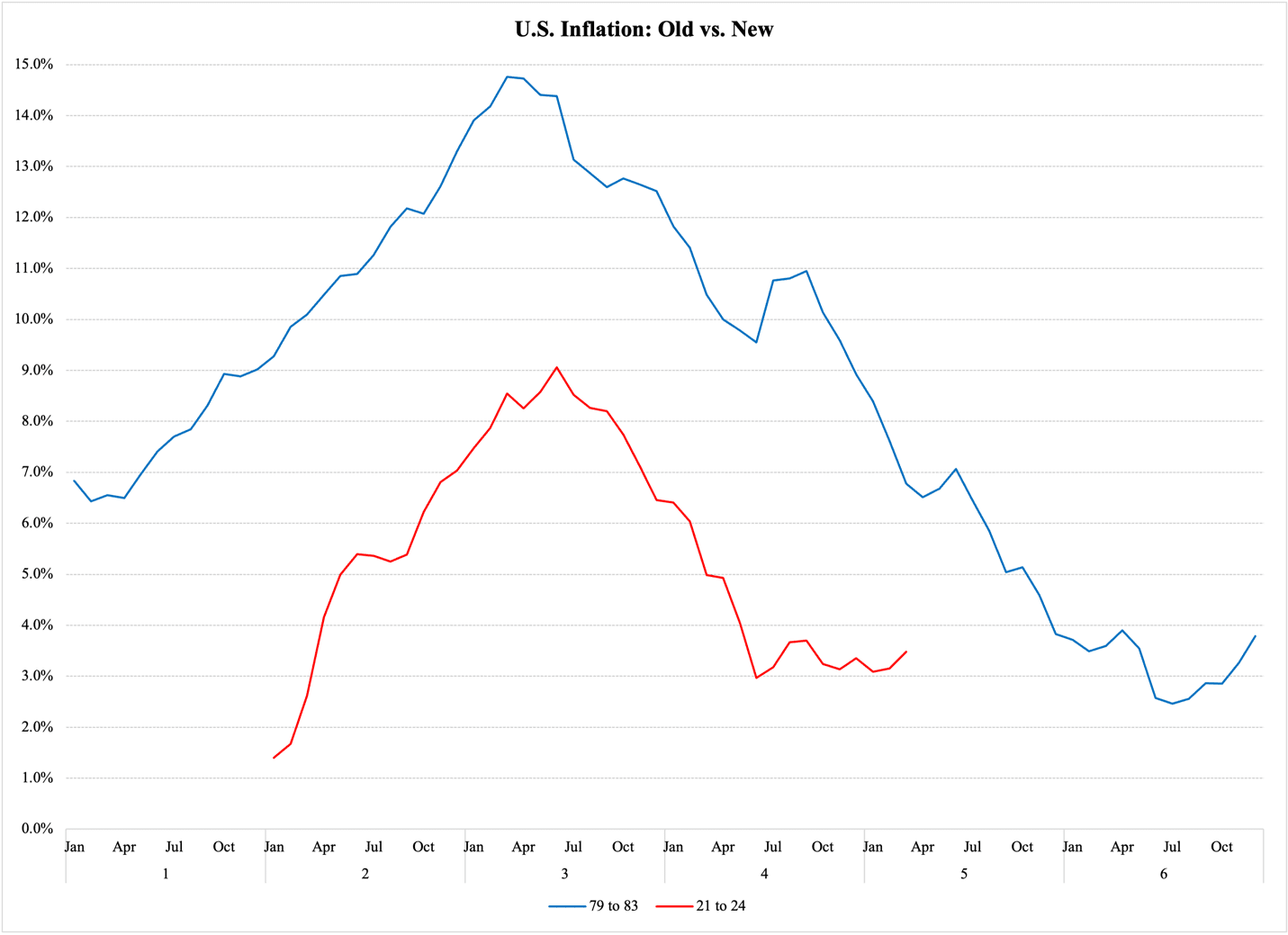

To conclude, let us take a step back and compare our recent CPI inflation experience (red) with the one that plagued the U.S. economy a bit over 40 years ago (blue).

Figure 2

There is an important difference between these two episodes. In 1979-1984, unemployment soared alongside inflation, hence the term stagflation.

As the stagflation experience points to, inflation is not easy to get rid of. Back then, the peak happened in 1981, but it took almost two years before inflation was cut in half. Once the inflation episode was over, the inflation rate remained elevated for years.

In the recent episode, the halving of inflation took about a year. It is perfectly reasonable to expect it to remain elevated for at least 2024. However, as noted, inflation is unlikely to decline even as the monetary pressure has now dissipated. A coming article will discuss that.