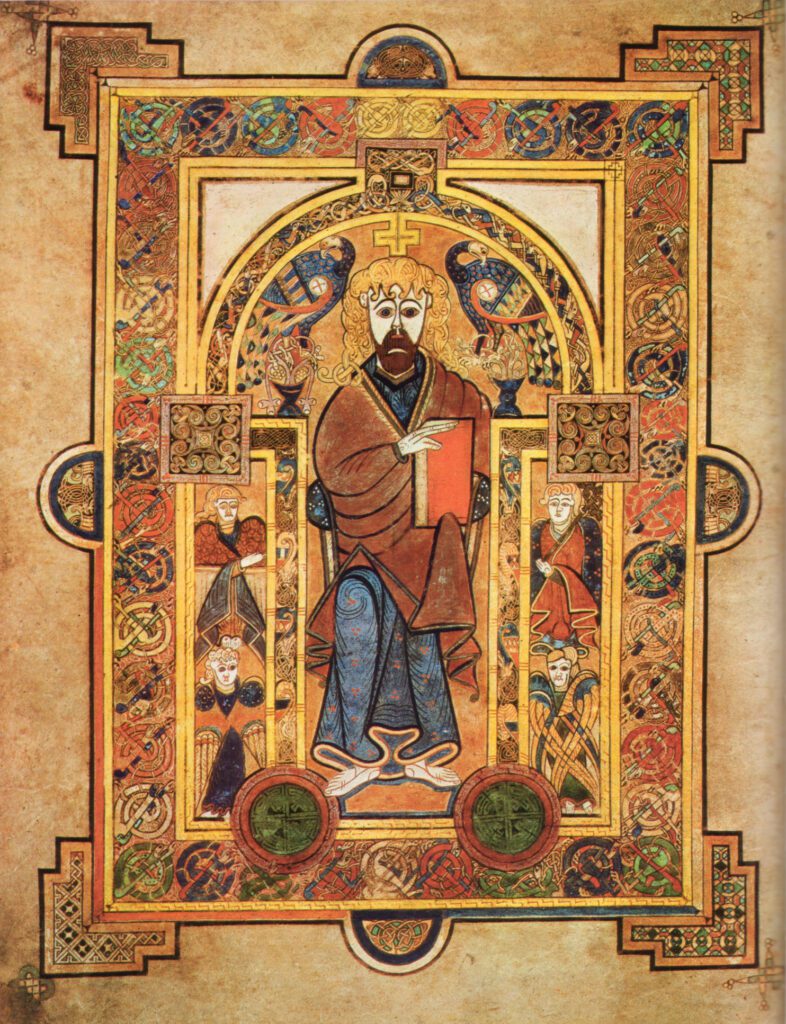

“Christ Enthroned” (circa 750–early 9th century), Folio 32v from the Book of Kells, found in the library of Trinity College, Dublin. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. As I Timothy 6:13-15 states: “I charge you to keep the commandment … until the manifestation of our Lord Jesus Christ … he who is the blessed and only Sovereign, the King of kings and Lord of lords.”

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

By encouraging an EUROPEAN IDENTITY we do not intend to promote a “western culture” which absorbs and dissolves all diversities in a leveling attempt. On the contrary, our aim is to enlarge this identity beyond the European boundaries, thus recovering that large part of our continent “outside Europe”—from Argentina to Canada and from South Africa to Australia—which looks at the old continent not as a distant ancestor but as a real homeland.

—“Manifesto of European Identity,” Associazione Culturale Identità Europea.

In the first part of this essay, I considered the history of monarchy in the Americas, and particularly in the United States. I also gestured towards the idea of a ‘Royal America,’ made up of a variety of cultural traditions and peoples spread across the New World, from Canada to South America, and all points in between.

In Latin America, after the shock of the conquest, Spanish colonial administration saw the erection of two (eventually four) viceroyalties, which in law were the equal of the Kingdoms of Spain. But they were further divided according to whether an area was mostly Spanish and Mestizo or Indian into the republic of the Spanish and the republic of the Indians. This latter category encompassed autonomous territories ranging in size from the New Mexican pueblos to the Principality of Tlaxcala, ruled by its native princes. All of these autonomies were suppressed by the nascent Latin American republics in the 19th century. The French co-existence with their Indian allies was proverbial, as was the British Crown’s encouragement of their settlers’ rapacity against them. But with the treaty of 1763 giving Canada to Britain, the Crown was as obligated to defend their new Indian subjects’ rights as it was those of its new French Canadian subjects. This was the origin of the Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act, neither of which was popular amongst the oligarchies of the 13 colonies, thereby helping to cause the American Revolution as a result. But in contrast to the settling of the American West—with the exception of the Riel Rebellions—the consolidation of Western Canada was relatively peaceful and equitable. Even those rebellions were not against Queen Victoria: Riel himself led the Metis in the name of the Queen.

As far as slavery went, the Black Codes of the French and Spanish required far more humane treatment of the slaves then prevailed in the British American colonies. Even there, however, during the Revolution, the King emancipated those slaves who joined the Loyalists—hence the presence of their descendants not only in Canada, but in Sierra Leone and the Bahamas. Emancipation by the British, French, Spanish, Dutch, Danish, and Brazilian Monarchs was gradual, and far easier than in the United States. As a result, racial relations in those countries, although not without difficulties, have been nothing as severe as we have had.

All of these historical considerations, alongside the increasing fragmentation leading up to the election of 2016, caused me to think along several different lines. One was the idea of building an American patriotism rooted in the United States as they really are, rather than dependent upon the dying civic religion. The second was an exploration of monarchy in the abstract. The result was my first (and only, so far) attempt at a novel: Star Spangled Crown. Set in a relatively close future, its conceit was an already established and functioning American monarchy, through which I was able to look at all of the aspects of Americana we have discussed here. Although I highly doubt that anything remotely like what is described in the book shall ever happen, it proved an interesting exercise in stimulating thought and debate.

The subsequent Trump and Biden administrations; the transformation of the European Union into a secularising superstate; the growing claims of Vladimir Putin to be the defender of ‘Christian values’ while American and Europe appeared to be struggling to make his claims credible; the rise of Viktor Orban and other voices in Central Europe as seemingly lone voices of sanity; and at last the war in Ukraine pushed me along as they did everyone else. Moving to Europe in 2018 also helped crystallise my thinking about America, Europe, and monarchy, as did writing a biography of Bl. Emperor Karl. I became convinced that the answer to America’s spiritual and cultural – and so political – ills lay in the Mother Continent, and there, in the lands of the former Habsburg Empire.

From the time that I was in high school, I corresponded with Archduke Otto von Habsburg, and together with all the reading I described in the first instalment, he was a leading influence on my thought. Standing as he did between two worlds—the Ancien Regime as exemplified by Austria-Hungary; and the post-World War II Europe of Christian Democracy, the Soviet menace, and European Union—he had a wealth of wisdom from which to draw. He was a great one for maintaining one’s ultimate principles while attempting to apply them effectively in the present, yet always remaining mindful that this present would soon pass away and be replaced.

Of the five European Conservative points we considered in our first instalment (altar, throne, subsidiarity, solidarity, and Christendom), restoration of altar and throne would never be permitted by either the Soviets or Americans, and the Catholic hierarchy itself tacitly abandoned the first after Vatican II. Surviving European states accordingly wrapped up subsidiarity and solidarity in vague ‘Christian values,’ and attempted to retool Christendom into what would become the European Union. Rather than pursuing a Habsburg-led Danubian Federation—which notion, originated by Franz Ferdinand, had been espoused by Bl. Karl, Zita during her ‘regency,’ Otto himself before and during World War II, and even Churchill—the Archduke threw himself into creating a European Union that would incarnate the spirit if not the form of the Holy Empire. This was a vision which I came to share, while hoping that better times for Church and State might come.

Unfortunately, when that day seemed to arrive in the form of the fall of the Soviet Bloc, many such dreams were ultimately dashed—not least by the action of my government in vetoing restoration in the Balkans, as mentioned in the last instalment. Both the United States government and the EU itself slowly transformed over the following decades into machines for imposing infanticide, perversion, and latterly euthanasia on their own peoples, the newly freed Central European countries, and the Third World. Having died in 2011, the Archduke was spared the sight of much of this. Two years later, Benedict XVI, who had shown such vision and wisdom in his pontificate, resigned the Papacy and was replaced with a very different sort of pontiff.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin had been presenting himself as the defender of Christian values against the hideous strength rising in the West. Indeed, the current cold war between the United States and Russia stems from the reaction of President Obama in 2012 to Putin’s anti-homosexual proselytisation law—long before the problems in Syria and Ukraine. At that time, given the way in which the Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna was allowed to travel about her homeland and decorate various government officials with dynastic orders, the suspicion rose that Putin favoured restoration as a way of reinvigorating Russia. These hopes reached their apogee in 2015, when Vladimir Petrov, deputy of the Russian Legislative Assembly for the Leningrad Region, proposed as much; because he was a member of Putin’s party, it was widely thought this showed Putin’s approval for the idea. But that was as far as it went. The reemergence with official approval, since the Ukraine war began in 2022, of red flags and statues of Lenin and Stalin leads one to believe that Putin no longer favours restoration, if indeed he ever did.

In the meantime, Orban’s Hungary—and Poland, until the recent change in government—have appeared as islands of sanity in a world going increasingly mad. Alongside common sense measures in defence of marriage, family, and public morality—and the reining in of their chief opponents, the judiciary and media—the Orban government returned the name of the country to its pre-Communist title, restored the old royal names and officials for counties, began the rebuilding of the Royal Palace in Budapest, and employed two senior Habsburgs as ambassadors. There were echoes elsewhere in the neighbourhood, as similar social measures began to appear here and there in Slovakia, Croatia, and Slovenia. Czechia dropped ‘republic’ from its name and rebuilt the Habsburg Marian Column in Prague. In, with, and under all of these movements, the cultus of the newly beatified Emperor-King Karl spread. One began to hope that perhaps something approaching the old Habsburg-led Danubian Federation might emerge. Perhaps such a grouping could resist the blandishments of both Putin and Soros, and one day act as a catalyst for the emergence of the kind of Europe for which Otto and his collaborators had worked so hard and diligently.

In 2018, I moved to Austria to begin studying for an advanced degree in Catholic theology. I had visited a number of parts of Europe over the years and met with Monarchists in many parts of Europe on their home turfs. Certainly, both in America and Europe, I had partaken of the culture of remembrance—the beatification of Emperor-King Karl in Rome, and veneration of his relics at a number of shrines; attendance at molebens in honour of Nicholas II; the wreath laying at King Charles I’s statue in Trafalgar Square and the following Mass at the Banqueting House; requiems for Louis XVI; the changing of the Guard of Honour at the Savoy Tombs in the Pantheon; and more of the like. But living in Europe would be quite different.

There were the annual audience reenactment in honour of Bl. Karl and Zita at Brandys in Czechia, where reenactment units are reviewed by a senior member of the Imperial House (and the similar Kaiserparade in Korneuburg); the annual requiem for Otto in the Kapuzinerkirche in Vienna, where he rests among his fathers; and the monarchist student fraternities in Austria, with their singing of the Imperial anthem at every function. These and a great many other such functions showed at once a deep Monarchist sentiment that lies near the surface of a great many people—not just for the Habsburgs in Central Europe, but for both of the branches of the House of Bourbon in France, or Duarte in Portugal, and a number of others. But, of course, sentiment is not the same as a burning desire for change, although it does imply a hope of one kind or another.

Beyond that, my travels from Ireland to Ukraine showed how well Deep Europe—that Continent of innumerable local heritages, ways of life, and customs—still survives. The observation of the feasts of the Church year, the many church shrines, the local museums, the old castles and manors in which the old families still dwell or have returned, the local guilds and organisations, re-enactment units, and so much else that are the common built and intangible heritage of all Europeans, together reflect the Church and State under which they were slowly accumulated. The natural environment combines with these to form the ineffable landscapes that make up the Continent.

My theological studies of the Catholic variety reinforced my belief in Christ, His Church, and His Sacraments as the means of Salvation, and of escape from the trap of the Fall of Man. But I learned a few things of strictly political importance. Chief of these was Christ’s union, at the Last Supper, of the Davidic Kingship to which He was rightful heir, with the nascent Communio of the Church—as a result of which, Christian monarchy was seen as a participation in the Kingship of Christ. This was symbolised by His washing of the Apostles’ feet—a reenactment of which became a key element of the Maundy Thursday ceremonies at every Catholic Court in Europe. Practised by the Monarchs of Austria-Hungary and Bavaria until 1918 and Spain until 1931, the sole remnant—sans actual footwashing—is King Charles III’s annual distribution of ‘Maundy Money.’ This tradition began with a law enacted by Theodosius the Great in 380, when baptism became entrance into Roman Citizenship as well as into the Church.

From that time, the Empire—East and West—along with the various Kingdoms that grew up on her soil, and those that followed in formerly barbarian lands, were seen as the ‘matter’ of the Christian body, of which the Church was the ‘form’ or soul. This was why Muslims, Jews, and heretics could not be full members of the body politic. After the Protestant Revolt, this would be turned against those who held on to Catholicism after forms of Protestantism became the Established Churches in various countries. Of course, while accepted in theory by virtually everyone, adventures such as the split between Rome and Constantinople, the Guelph and Ghibelline feuds, and the Investiture controversies in various countries centred on practical application of these ideas to specific contemporary issues. But these were not ideological, as such. Ideology emerged with Martin Luther’s revolt.

Nevertheless, as I have written elsewhere in these pages, it also became obvious to me that Catholics, Orthodoxy, and the state churches of Northern Europe had each retained an awareness of certain important elements of that Res publica Christiana. We Catholics were certainly aware of the necessity of an independent religious leader for Christendom—the Pope; we also remembered well that the Church in each country must not only be independent, but attempt to shape the countries in which it found itself. This reality is encompassed in the devotions to the Sacred Heart, the Kingship of Christ, and the Queenship of Mary, and symbolised by national consecrations thereto. The Orthodox, despite the Russian Revolution in 1917, retain in their liturgy a clear ideal of the place of the Imperium and Monarchy in the Christian State. Despite the doctrinal problems attendants upon becoming governmental departments, the Protestant state churches of Northern Europe had at least held on more or less to the position in government and society once held by Christianity—albeit lost to the Catholics and Orthodox via many violent revolutions, and now through the passage of time virtually forgotten by them.

Looking at all of this, I came to agree with Fr. Aidan Nichols: “Catholicism, as Orthodoxy, has, historically, regarded the monarchical institution in this light: raised up by Providence to safeguard the natural law in its transmission through history as that norm for human co-existence which, founded as it is on the Creator, and renewed by him as the Redeemer, cannot be made subject to the positive law, or administrative fiat, or the dictates of cultural fashion. Let us dare to exercise a Christian political imagination on an as yet unspecifiable future.” He also speaks of a revived Imperial institution “ensouling” the EU, as it were: “The articulation of the foundational natural and Judaeo-Christian norms of a really united Europe, for instance, would most appropriately be made by such a crown, whose legal and customary relations with the national peoples would be modelled on the best aspects of historic practice in the (Western) Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine ‘Commonwealth.’” In short, a Christian, Imperial and free European monarchy made up of constituent monarchies was what he had in mind—and ultimately, this is the vision I have come to hold.

But in all of this, what of the land of the Stars and Stripes, my homeland? Where, in such a vision, do America and the other settler lands fit? In days of yore, the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and various parts of Asia and Africa received the most adventurous, cantankerous, eccentric, or just bizarre elements of the European population. Whether as initial pioneers or later immigrants, they were the folk who, to a lesser or greater degree, did not fit in. Those who stayed behind were either content with their lot or not terribly adventurous. Ironically, although the outgoers had to deal initially with indigenous resistance, with the hardships of a far-less civilised environment, and in many places with ongoing racial issues, they were spared the horrors that befell their more sedentary cousins in the Mother Continent in the form of the Two World Wars and—for half of them—life in the Soviet Bloc. For all of that, as Otto von Habsburg once remarked, “Europe really extends from San Francisco to Vladivostok.”

This reality was for long obscured by distance, but globalisation is a fact of life today. It struck me a couple of years ago, having flown from Austria to the United States and back twice within a week and a half, that for my fathers, one trip either way was usually a life sentence. Thanks to the speed of travel and the internet, the two sundered halves of the Christian European people interact more and ever more. The evil effects of that reality are all about us, from Antifa burgeoning in the United States to BLM chapters arising in Europe. But it is also true in a more positive sense. More and more young Americans are discovering the untapped riches of European Christian and Conservative thought; more and more young Europeans are discovering the energy and organisational ability endemic to the former colonials. Together, despite the darkness of the hour, what may they not accomplish?

At 63, I have far more yesterdays than tomorrows. But if history has taught me anything, it is that, normally, accomplishment of any great task can take a number of lifetimes. I am content to spend whatever time I have left in helping to-day’s young people in accomplishing the realisation of the ideals we have been examining in these articles, knowing that I am unlikely to see the results. But by the same token, Lenin, of all people, was quite correct when he said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” On that note, I shall leave the last word to Archduke Otto: “Sometimes, like the Jewish people of the Old Testament, we think of everything in an overly earthy way. They were waiting for the Messiah as a king in the political sense, and we believe that the empire should be expressed in the forms known in history. In reality, however, the Christian empire is more the spirit of solidarity, the Pax Christi thought, the practical implementation of gospel principles, the cooperation of free peoples who acknowledge the Kingdom of Christ.”