While Brussels celebrates past successes, the removal of the veto, the erosion of the Single Market, and accelerated enlargement threaten to turn the European project into something very different from what Spain and Portugal signed up to in 1986.

As I noted last week, there are some indications that Europe may actually be on the back end of its recession. While it is too early to tell definitively which way the continent’s economy is heading, there is some anecdotal evidence with a positive tone to it.

According to the Budapest Business Journal,

Regular average gross earnings (without premiums and one-month bonuses) were estimated at HUF 598,400, being 14.9% higher than in the same period of the previous year. … Average net earnings reached HUF 437,800, excluding tax benefits, and HUF 452m700, including them, being 13.9% and 13.7% higher than in March 2023

This is very good news for the Hungarian economy. Here is the best part:

Real earnings were up by 9,9%, along with a 3.6% increase in consumer prices compared to the same period of the previous year.

If Hungarian businesses can handle this increase in labor costs, households are bound to give the Hungarian economy a much-welcome boost in the coming months.

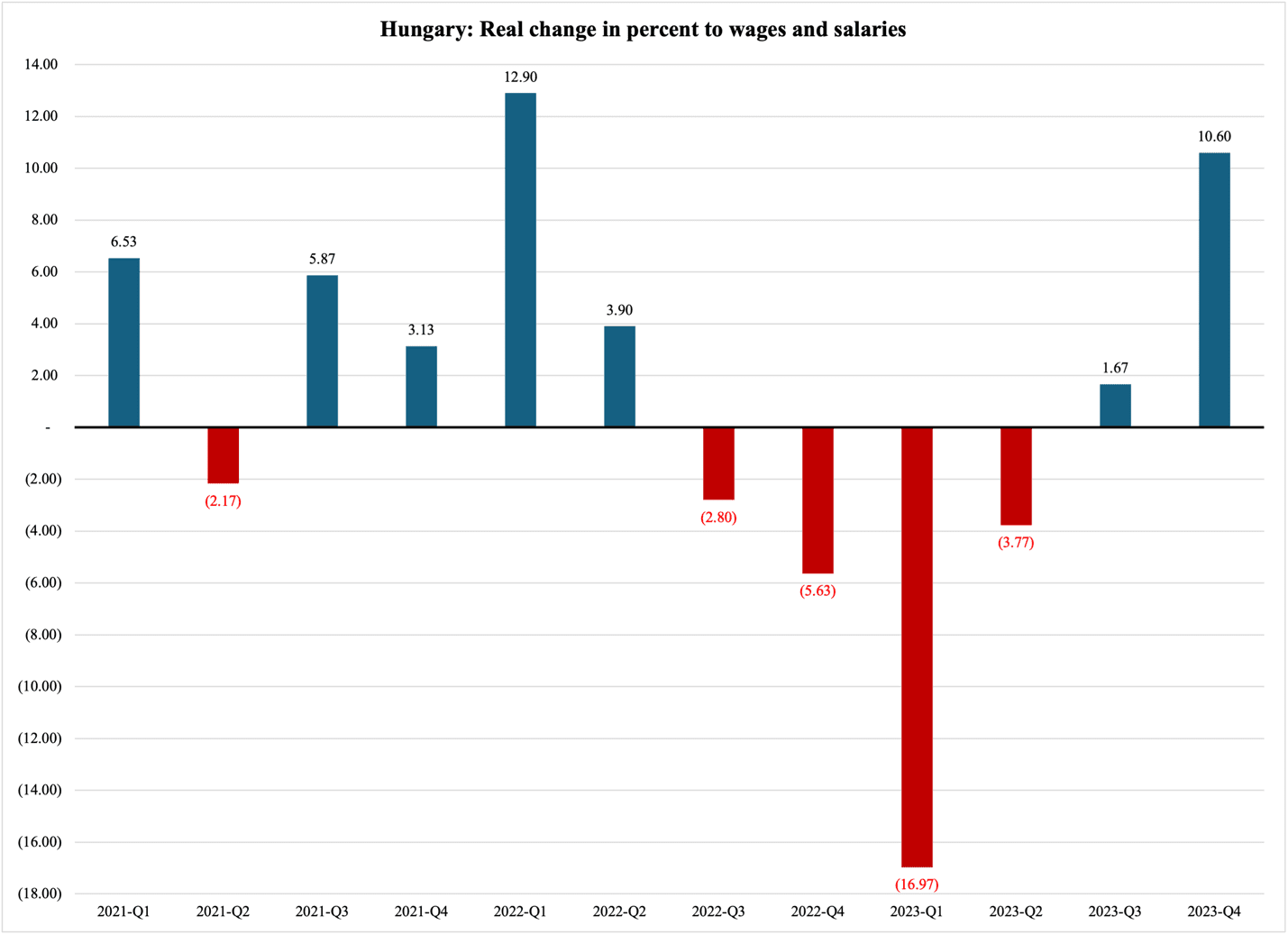

I would not translate the entire real-wage increase into growing spending; as reported in Figure 1, Hungarian consumers have had a tough time through the recent inflation episode, with real wages and salaries falling through four quarters in a row. After tough financial episodes like this, consumers tend to want to shore up their financial margins before they resort to more spending. Nevertheless, this real-wage increase is good enough to bring about a rise in spending as well:

Figure 1

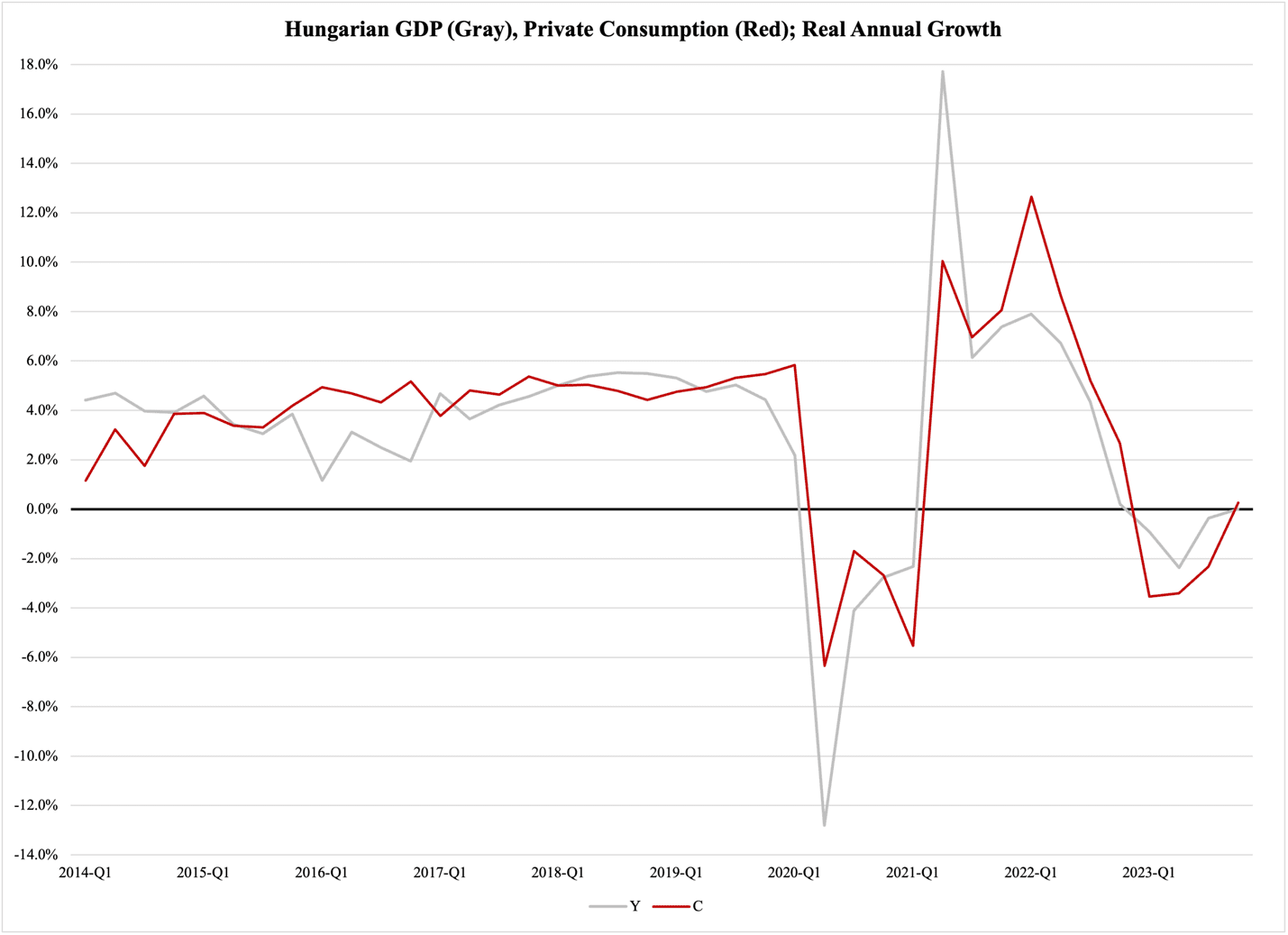

In real terms, consumer spending equals half the Hungarian economy. Therefore, its ups and downs have a major impact on the economy as a whole. Figure 2 shows how the episode with high inflation caused a dip in total economic activity, including consumer spending:

Figure 2

The return to positive growth in private consumption will come at the best possible time for the Hungarian economy. Its unemployment rate has risen recently but could have reached its peak. Last fall, unemployment started rising from its 3.8-4% long-term stable trend; reaching 4.2% in November and December, it topped out at 4.6% in February and then dropped to 4.4% in March.

Youth unemployment underwent a similar trend, rising from a 10.5-11% long-term trend to 13.8% in November and 15.7% in February; the March figure was 15.2%.

The good numbers for real wages will help secure February as the peak month for Hungary’s jobless rates. However, there is a risk that the positive effects of increased consumer spending are drowned out by a decline in exports. Like most other countries in Europe, Hungary is heavily dependent on its foreign trade, with exports being approximately 100% of GDP.* This means that businesses in Hungary sell products abroad for a gross value that is twice as high as total household spending in the country.

Again, this is a normal situation for European countries. It shows how dependent they are on foreign trade, but it also shows how vulnerable they can be to dips in foreign demand for their exports. This is exactly what has happened in Hungary. Last year, there was a significant change in exports from Hungary:

The dip in exports reduced economic activity by HUF 415.6 billion in 2023, again adjusted for inflation. This decline was big enough to negatively affect business investments, causing them to drop by 2.8%.

A small rise in private consumption of 0.25% made no material difference during 2023, but a stronger increase is to be expected for the first quarter of this year. The second-quarter numbers should be even better for consumers, especially since the Hungarian National Bank last week reduced its base interest rate by 0.5 percentage points to 7.25%. This will help credit-driven consumption, including mortgage-financed home buying, spending on consumer durables, as well as other credit-card-funded outlays.

The rate cut may also have a positive effect on exports. In theory, this rate cut should depreciate the Hungarian forint vs. the euro: with lower interest rates in Hungary relative to the rates in the euro zone, investors would prefer to invest in the latter vs. the former. Therefore, there should be an outflow of money from Hungary; as people pull their money out, they sell the Hungarian currency, causing it to depreciate.

When the currency depreciates, exports from Hungary become relatively cheaper than they were before the rate cut.

In practice, the forint has not lost value vs. the euro since last week’s rate cut. A quick review of websites tracking exchange rates suggests that the opposite might actually have happened: the forint has been slightly strengthened after the rate cut. There are two main reasons why this would happen, one being that the forint is small vs. the euro, and moderate changes in central-bank interest rates have at best marginal effects on the exchange rate.

The second reason is that investors expect the European Central Bank to cut its policy-setting interest rates at its meeting next week. This cut is dicey given the inflation situation across the euro zone, but it will nevertheless likely happen. When it does, it is bound to have a small but noticeable depreciating effect on the euro’s exchange rates.

If Hungarian exports are not affected positively by the changes in interest rates from either the Hungarian or the European central banks, we can expect at least a small, positive impact on business investments in Hungary. The rate cut by the Hungarian central bank would not have this effect on its own, but when combined with a solid rise in consumer spending, it is likely to encourage entrepreneurs to expand their businesses for the domestic market.

All in all, Hungary remains at the forefront of the European economy. With low unemployment, a well-managed central bank, resilient consumer spending, and a business-friendly government, Hungary has a strong economic future to look forward to.

*) This is gross exports. Imports are counted as available resources in the economy, while exports are counted as spending; the difference between the two is known as net exports. Before imports are subtracted, gross exports can exceed 100% of GDP. This happens in countries with large imports of inputs for the export industry.