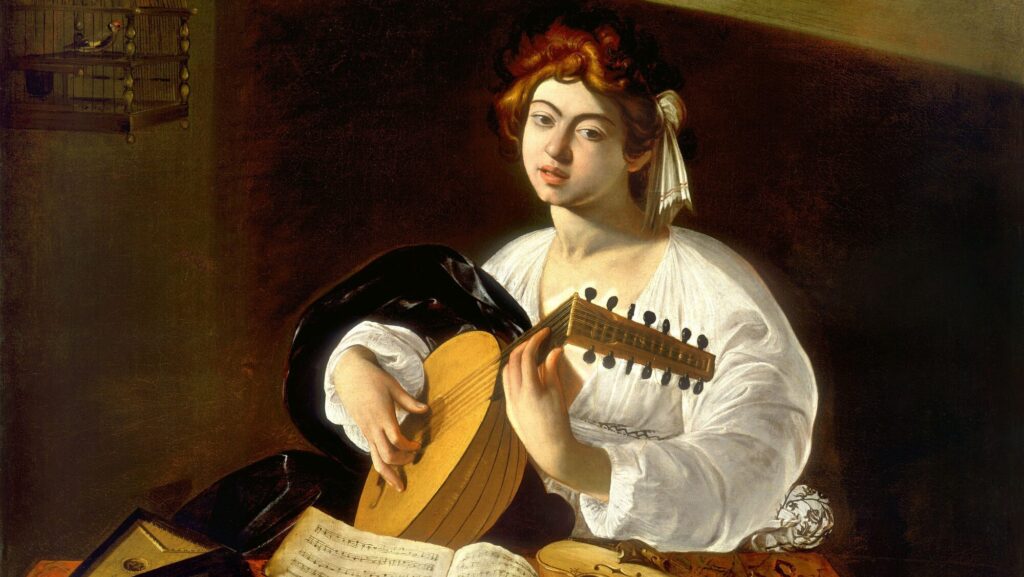

“The Lute Player” (1596), a 100 x 126.5 cm oil on canvas by Carvaggio (1571–1610), located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Roman residence of the Caetani family, Palazzo Caetani, hosted Carvaggio in 1601-1602.

Rome is not a musical city; in fact, I would call her utterly anti-musical. Had I spent the last few years in a more civilised town, I might have been able to make much more progress in my artistic studies. But I believe it is not too late, and amending the mistakes made will help largely rectify them. It will pain me to be away from you for so long, all the more so because I have been away for so long now; but you understand that we can only really achieve something when we set ourselves a goal in life, a goal that we want to follow to the utmost.

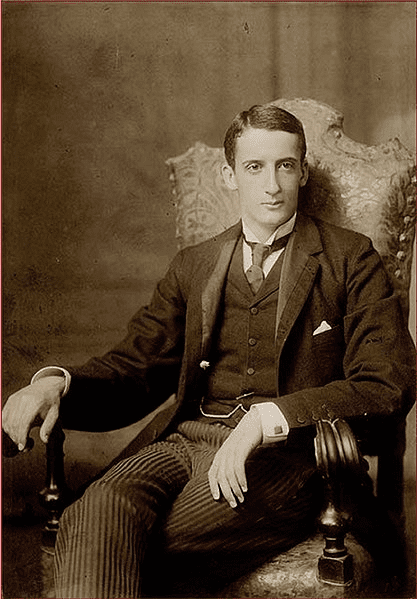

—Letter from Roffredo Caetani to his father Onorato Caetani, Tacoma, dated the 30th of September, 1893.

Roffredo Caetani (1871-1961) was the last male scion of an illustrious Italian family that was extremely influential for more than nine centuries. Although he had a son and a daughter, his only son Camillo died in Albania on the 15th of December, 1940, fighting against the Greek army. Camillo was only 25 years old when he died. Roffredo’s subsequent frantic attempts to see that the family titles could continue along the female line came to nothing. Moreover, in 1948, all noble titles were officially abolished in Italy.

In my opinion, this personal tragedy is one of the most poignant matters described in the biography Roffredo Caetani compositore: La vita, le opere, il tempo, written by Dutch musicologist Paul Op De Coul and published in 2022. In this impressive study, Caetani emerges as a shy and introverted man, who valued discretion above almost anything else. But he is also shown to have been a man who possessed a deep emotional life and who long struggled with the question of whether his life still had any meaning after Camillo’s death.

The music of Roffredo Caetani plays no significant role in contemporary musical life. And yet I do not hesitate to call him an important composer. A child prodigy too: constantly encouraged by his loving father, he started composing at age 11. Throughout history, by the way, Italy has produced noblemen-composers with some regularity. One of the most famous examples is Carlo Gesualdo, Principe di Venosa (1566-1613), who is better known for having murdered his adulterous wife and her lover than for his exceptionally experimental music. Other examples are Alessandro Marcello (1684-1750) and his younger brother Benedetto (1686-1739), descendants of a Venetian family whose ancestral line can be traced back to Roman Antiquity. Last but not least: the eccentric count Giacinto Scelsi (1905-1988), author of the most superficial autobiography (Il sogno 101) I have ever read, but a highly original composer.

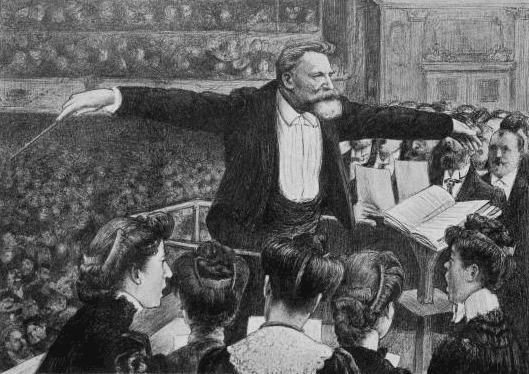

These noble composers had at least one thing in common: they did not have to worry about their popularity. They had ample economic resources and a very extensive social network. But that noble privilege also has a downside. Benedetto Marcello, for instance, constantly struggled with the question of whether he would be taken seriously as a composer. Or would the music world see him as an amateur, a dilettante with no deeper musical significance? A century and a half later, similar discussions keep cropping up in Roffredo Caetani’s life too. His good relations with some French noble ladies opened all doors in Paris, both for Goffredo personally and for his music. Countess Élisabeth Greffulhe, in particular, worked tirelessly at the service of Roffredo and his musical pursuits for almost all her life. But that also created mistrust. What does this Sunday child from Italy actually have to say as a composer? Isn’t he just a spoilt amateur? The prominent conductor Édouard Colonne lost all interest in Roffredo when he discovered that he was dealing with an Italian prince. Later, however, Colonne came around and in 1903 he conducted the first performance of Caetani’s Passacaglia for orchestra, but this was preceded by a lot of massage work.

A striking feature of Roffredo Caetani’s career is the fact that, as a composer, he originally devoted himself mainly to chamber music genres and orchestral works; vocal music and opera remained out of the picture for a long time. Sure, he was walking around with plans for a major operatic triptych as early as 1894, but nothing came of it. Only in 1908 did he start working seriously on the libretto of what would become his first opera, Hypatia. The world premiere of this opera would not take place until the 23rd of May, 1926, tellingly not in Italy but in Germany. Hypatia was then performed in Weimar, in the German language. One of the critics present even noted that although the composer was an Italian, his music sounded ‘completely German’! Italy did not follow suit until more than 30 years later when, in 1958, Hypatia was performed in concert in Milan.

As mentioned, Roffredo’s initial interest was exclusively in instrumental music, an exceptional phenomenon in Italy at the time. This preference certainly had to do with the fact that Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914) was young Roffredo’s piano teacher. Sgambati had been a pupil of Franz Liszt (1811-1886), and Liszt, in turn, was Roffredo’s godfather. As a pianist and composer, Sgambati did very much for the emancipation of instrumental music in Italy. None other than Richard Wagner was so impressed by Sgambati’s two piano quintets that he arranged for the works to be published in Germany. It is no coincidence that Caetani also composed a piano quintet some 15 years after Sgambati, and had it published as his Opus 4.

Like Brahms and Liszt, Wagner was instrumental in Caetani’s compositional development. Remarkably, Verdi’s music meant very little to Caetani, in contrast to Wagner’s music that Caetani loved and studied deeply. Later, in the years when he lived mainly in Paris, Caetani also appears to have developed a great interest in Stravinsky. For instance, he attended the performance of Petrushka on three consecutive evenings, on the 15th, 16th, and 17th of June, 1911, immediately after Stravinsky’s ballet had premiered on the 13th of June, 1911. Stravinsky’s influence can clearly be felt in, for instance, La commedia d’un musicista for solo piano from 1936-37.

Towards the end of his life, Caetani befriended Count Guido Chigi Saracini, the driving force behind the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena. The first edition of the Settimana Musicale Senese, organised by the Accademia in 1939, was completely devoted to the then still largely unknown oeuvre of Antonio Vivaldi. The rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi’s music in the 20th century really grew wings in Siena in that year. Italy became aware that its musical history had so much more to offer than romantic opera alone. Indeed, from 1600 to 1750, Italy, not Germany, had been in the forefront of instrumental music. This observation no doubt pleased Caetani, who was after all primarily a composer of instrumental music.

But now it is high time for the music of Roffredo Caetani himself to be rediscovered. The first steps have already been taken and the publication of Paul Op De Coul’s monumental biography will undoubtedly accelerate this process.

In 2014, Brilliant Classics released a CD on which Italian pianist Alessandra Ammara plays a number of Caetani’s piano works, including the monumental, more than 45-minute Piano Sonata, Op. 3. A recording of the two string quartets, played by the Alauda Quartet, followed two years later on the same label.