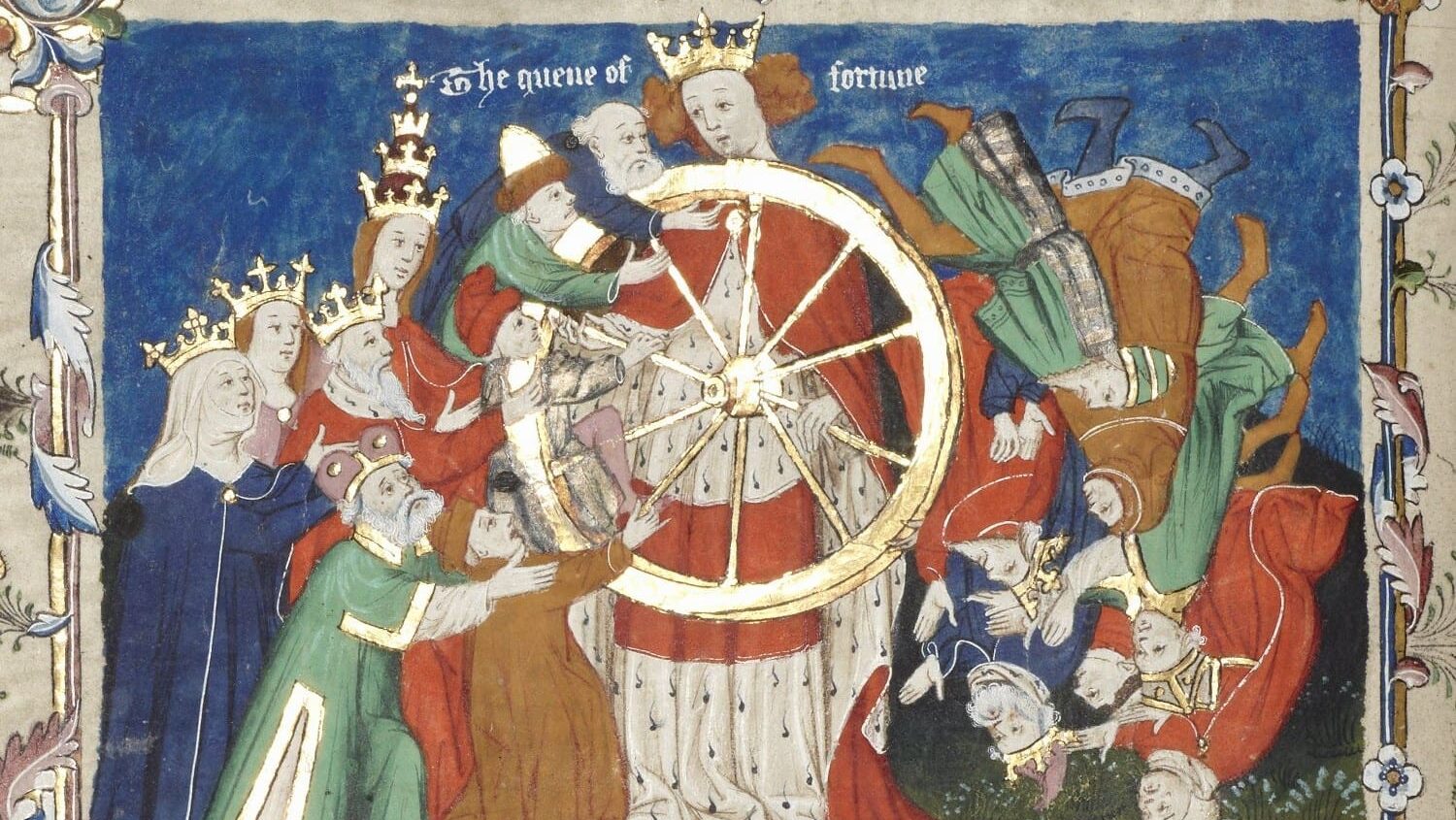

Illustration from John Lydgate’s Siege of Troy (mid-15th century), showing the Wheel of Fortune turned by the Quene of Fortune. On the left, Dame Doctryne is accompanyied by two male figures, Holy Texte and Scrypture, and two female figures, Glose and Moralyzacion.

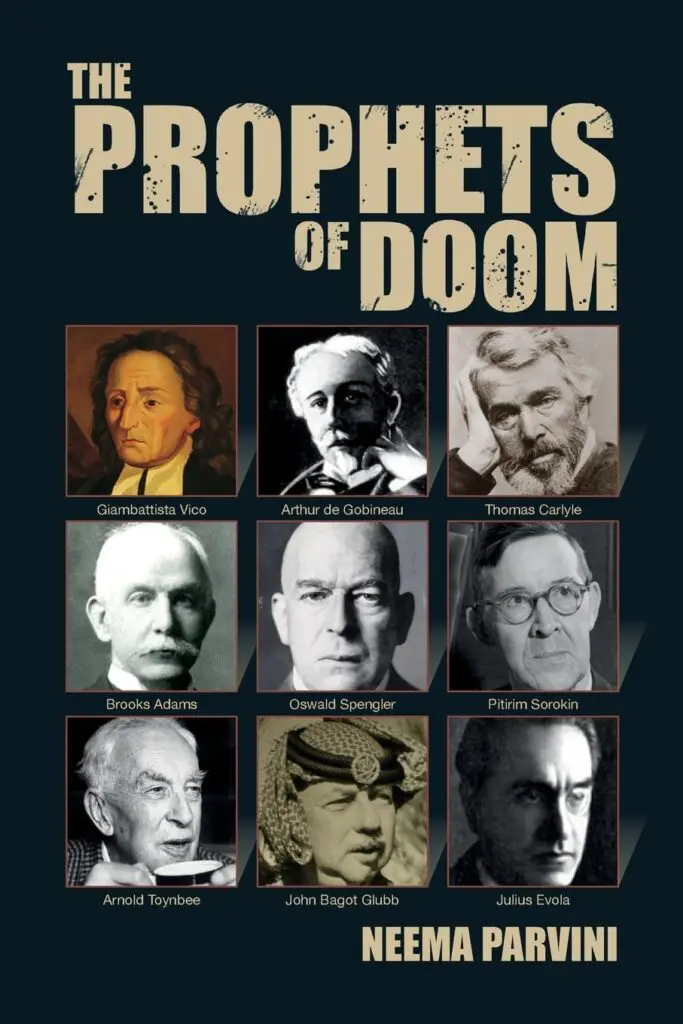

In The Prophets of Doom, Neema Parvini’s subject is the study and interpretation of history. Since the 18th century, historical writing has been informed by the Whig idea of progress, the idea that history is one long march of moral and material improvements. This progressive view of history had its culmination in Francis Fukuyama’s view of the End of History in which liberal democracy and capitalism have triumphed decisively throughout the world. Proponents of globalization have continued to promote the progressive view of history and Parvini begins his book by quoting former British prime minister Tony Blair who said that debating globalization was like debating whether “autumn should follow summer.” But Parvini then goes on to cite the anguished quote of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, that the Russian invasion of Ukraine “marks the end of globalisation.” Perhaps the global march of ‘progress’ is not so inevitable after all.

All the thinkers discussed in the book embrace a cyclical view of history and share a belief in “the inevitability of civilisational decay and eventual collapse.” In the first chapter, Parvini provides useful outlines of the differences between the cyclical and linear views of history. The former views history as an ongoing pattern of rise and fall, while the latter has a definite endpoint. In the progressive philosophy, that endpoint is the advance of science and technology to such an extent as to create a material, moral, and social utopia. However, the linear view has also been embraced by many Christians—perhaps most notably by St. Augustine in his City of God—who see the Second Coming of Christ as their endpoint. Other Christians, however—such as St. Bede the Venerable and Geoffrey of Monmouth—have been more inclined to the cyclical view.

The first of Parvini´s prophets is Giambattista Vico, professor of rhetoric at the University of Naples and author of The New Science (1725). This work was a critique of the rationalism propounded by Descartes and an attempt to counter what he saw as the anti-social character of Enlightenment thinking. Vico has been called the father of ‘historicism,’ the view that understanding anyone or anything from the past requires an understanding of their social and cultural contexts.

Vico posited three historical ages through which he claimed all civilizations pass: The Age of Gods, Age of Heroes, and Age of Men. The first age is preceded by a state of barbarism until the barbarians experience what Vico called “The Spark,” whereby they become aware of divinity, sin, fear, and so on. This leads to the establishment of religion, marriage rites, and burial rites. The Age of Gods proceeds with the establishment of a caste of priests who interpret the commands of God (or the gods) and give religious sanction to the newly established state. As society becomes more complex, there is a need for family and military alliances to defend the country. Thus, the Age of Heroes begins and is characterized by war and conflict. The cultivation of intellect and reason leads to the Age of Men, characterized by wealth and innovation. But at this point, man becomes too confident of his own abilities, leading to what Vico calls the “Barbarism of Reflection” and a new descent into barbarism, after which the cycles of history begin their work once more. Vico saw this pattern in the history of ancient Greece with the Age of Heroes being represented by Homer and the Age of Men by Socrates and Plato, their intellectualism being seen by Vico as ultimately fatal to civilization. Vico’s cyclical model, or variations of it, could also be applied to the history of the ancient Hebrews or even to the history of the United States.

One of the most interesting chapters in the book is that on Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle was both a reactionary and a revolutionary. Parvini states that while Carlyle “was a kind of perennial traditionalist, he was not afraid of drastic change or even revolution if a ruling class had become too corrupt or decadent to serve.” Parvini continues:

Carlyle was a man of many contradictions: profoundly religious yet a kind of atheist … vehemently opposed to free market economics yet a supporter of the repeal of the Corn Laws; he had a passionate concern for the poor and downtrodden yet resolutely opposed both democracy and the abolition of slavery; at once somehow lofty and prophetic yet stubbornly down-to-earth; he had many socialist admirers including, among others, John Ruskin, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, and yet he was unmistakably a man of the right committed to hierarchy and social order.

In Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (1845), Carlyle branded the conventional historian as ‘Dryasdust’ and accused him of “Dull Pedantry, conceited idle Dilettantism, —prurient Stupidity in what shape soever … Given a divine Heroism … they smother it in human Dulness … touch it with the mace of Death.” Carlyle promoted the Great Man theory of history, in which history is seen as primarily being driven by the deeds of great men. This is in stark contrast to modern views of history. Parvini writes:

It should be noted that the modern liberal order detests this idea and seeks to explain away such figures as Caesar, Cromwell, Napoleon … as being mere functions of structure or economic forces. This is not a mere debate over historiography, there is a deep metapolitical dimension to the banishment of the theory of the Great Man from polite discourse. The heroic is a genuinely terrifying idea to the liberal mind which must seek to make everything petty and small … the notion of a Great Man who stands up for his nation is such an anathema to their worldview. They cannot even process the notion, which is why every attempt was made to confine Carlyle to the dustbin of history.

Another interesting historical model was proposed by John Bagot Glubb—the British army officer who commanded the Arab Legion—in his essay “The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival” (1978). Glubb posited that empires have a lifespan of approximately 250 years and that their history follows a particular pattern. According to Glubb, empires move through six ages. The first two are the Ages of Pioneers, which is analogous to Vico’s Age of Gods, and the Age of Conquests, analogous to Vico’s Ages of Heroes. These two ages, which lead to the establishment of the empire, are followed by Ages of Commerce and Affluence. In the first of these, “The ancient virtues of courage, patriotism and devotion to duty are still in evidence.” In the second, the desire for money and wealth overrides all other values, leading to a gradual decline. In the Age of Intellect, which parallels Vico’s “Barbarism of Reflection,” there arises a supreme overconfidence in the power of the human mind to solve every problem. Finally, in the Age of Decadence, as in Vico’s Age of Men, all sense of duty is lost and there is a rise of pessimism and an intensification of hatred. There is also a decline of religion and the rise of a welfare state.

Glubb’s specialist subject was Arab history and, as Parvini notes, Glubb found in 10th century Baghdad much of the same decadence we experience today. Glubb writes:

When I first read these contemporary descriptions of tenth-century Baghdad, I could scarcely believe my eyes … The descriptions might have been taken out of The Times today. The resemblance of all the details was especially breathtaking— the break-up of the empire, the abandonment of sexual morality, the ‘pop’ singers with their guitars, the entry of women into the professions … I would not venture to attempt an explanation! There are so many mysteries about human life which are far beyond our comprehension.

Other figures covered in Parvini’s book include Brooks Adams, Arnold Toynbee, Oswald Spengler, and controversial writers such as Julius Evola.

Parvini has produced a well-researched, highly readable, and well-referenced book. It provides a series of excellent portraits of fascinating thinkers. Whatever one thinks of the individuals in question, their arguments continue to command interest, and should be better and more widely understood. With this book, Parvini has brought them out of the academy and into the light of public view once again.