Reading Eurostat’s latest inflation data, I am left wondering if Europe has unintentionally created a new form of inflation. If I am correct, economists and politicians across the continent have some real work to do in the coming months and years.

First, though, let us see what Eurostat has to say about inflation generally in the EU:

The euro area annual inflation rate was 2.5% in June 2024, down from 2.6% in May. A year earlier, the rate was 5.5%. European Union inflation was 2.6% in June 2024, down from 2.7% in May. A year earlier, the rate was 6.4%. … Compared with May 2024, annual inflation fell in seventeen Member States, remained stable in one and rose in nine.

One of the most positive news items in the Eurostat report is that 25 of the EU’s 27 member states now have inflation rates below 4%. The highest inflation rates for June were found in:

As the numbers from June 2023 indicate, Europe has made great progress in overcoming the recent, economically destructive inflation episode. This is especially true for Hungary, which for a short period had Europe’s highest inflation rate. However, thanks to intelligent monetary policy and fiscal restraint, the Hungarian National Bank and the finance ministry in Budapest were able to end an episode that, in other countries, could easily have led to even higher inflation rates.

In theory, it would be fair to criticize Hungary for still having an inflation rate of 3.6%, at the high end in the EU. In practice, though, the Hungarians do not have to worry too much about their current inflation rate. First of all, it is a vast improvement over the 25-26% rates they struggled with in late 2022 and early 2023. The return to more manageable inflation rates was faster than I had expected, and it was decisive enough to reassure investors, entrepreneurs, and households that the government had a firm grip on anti-inflation policies.

Secondly, Hungary dropped below 4% in January this year. Since then, average inflation has been just a hair above 3.6%; with the recent history of very high inflation, it is more important for the Hungarian National Bank to keep inflation stable and moderate than to try to push it further down.

At this point, lower inflation, while generally welcome, may come at too high a price for Hungary. The country’s economy remains strong, with unemployment in May at 4.3%. Furthermore, the Hungarian unemployment rate started rising last year, from 3.9% in September to 4.6% in February. However, since then it has ticked down, indicating a resilient economy where labor is in high demand.

This tells us that there is no longer any monetary inflation in the Hungarian economy; what remains at this point is a combination of traditional demand-pull inflation—caused primarily by a strong labor market—and structural inflation. Although there are no studies yet to establish this, there is anecdotal evidence that many countries that used economically restrictive measures during the pandemic also experienced a decline in competition in many markets. While larger corporations had the financial muscle to survive, smaller competitors did not.

As a result of dwindling competition, it is easier for remaining sellers to mark up prices above what would be merited by cost increases. The result is structural inflation, a phenomenon that has not been given sufficient attention by my fellow practitioners of economics.

Again, it is impossible to firmly establish whether or not Hungary has a problem with structural inflation, but there is definitely an element of demand-pull inflation in their current 3.6% rate. Since demand-pull inflation is governed by traditional market forces, there is no risk that it will reach problematic levels. Therefore, the only question that remains to be answered is to what extent there is structural inflation in the Hungarian economy.

Based on the Eurostat inflation figures, this is a question that needs to be answered in many EU countries. Three examples:

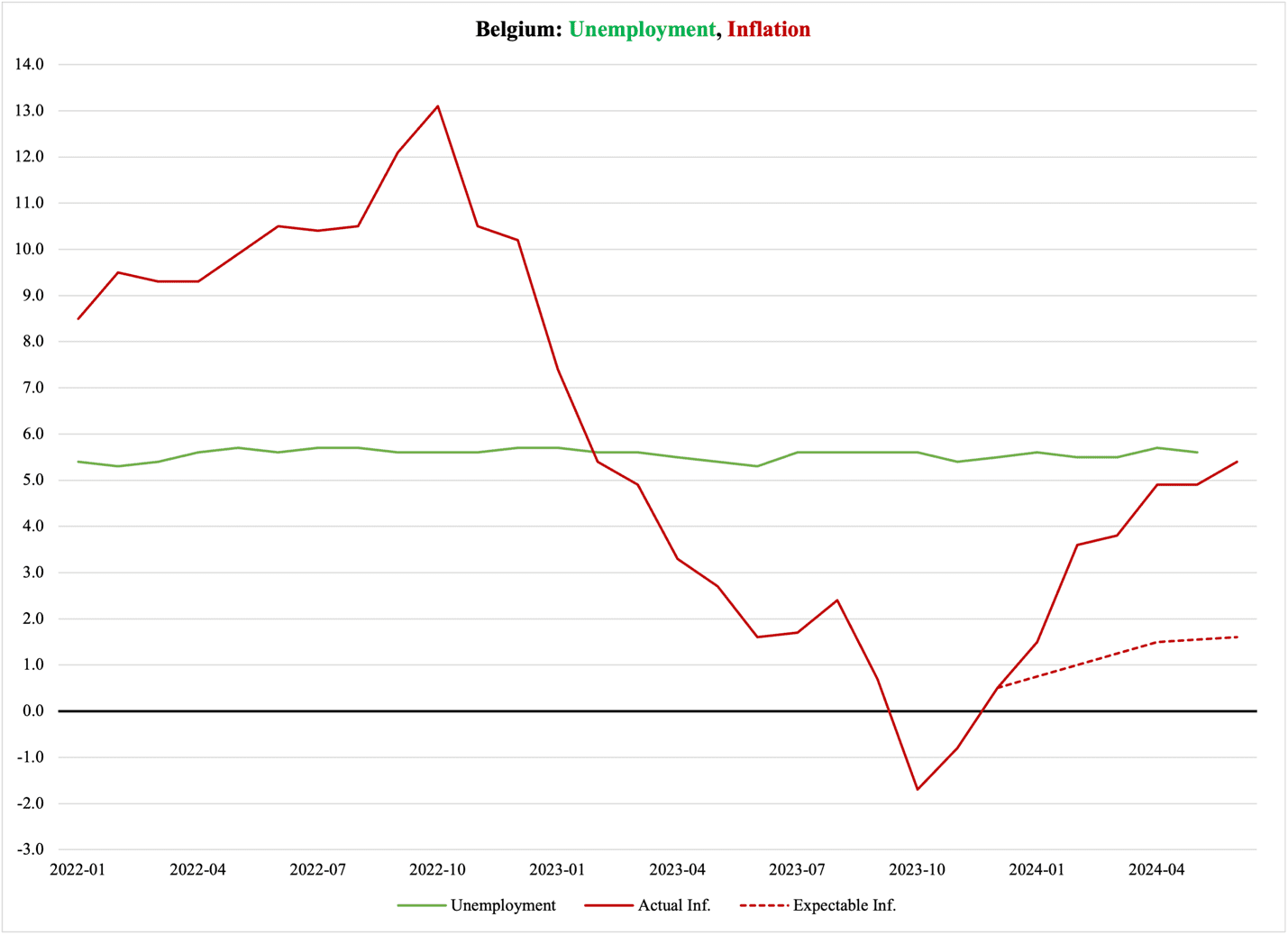

The most troubling example to date is Belgium. Since early 2022, unemployment has been stable in the vicinity of 5.5%—remarkably stable, in fact. At the same time, inflation is showing a troubling upsurge that defies standard economic theory. Figure 1 has the numbers; please note the dashed inflation line:

Figure 1

As soon as the monetarily created inflation peak was passed in late 2022, it was entirely expectable that the rate would fall to virtually zero, and even into negative territory for some time. However, there is no rational economic reason for it to surge back above 5%; given the overall performance of the Belgian economy, the dashed red line illustrates a far more reasonable inflation trajectory.

Overall, inflation in Europe is where one could expect it to be at this point, with the caveat that—generally speaking—there seems to be a fair amount of structural inflation built into these numbers. It is now incumbent upon economists in Europe to study this form of inflation, estimate its true size, and—if it does indeed represent a relevant share of remaining inflation—put together competition-enhancing policy recommendations for their respective governments.