While Brussels celebrates past successes, the removal of the veto, the erosion of the Single Market, and accelerated enlargement threaten to turn the European project into something very different from what Spain and Portugal signed up to in 1986.

In its first estimate of economic growth for the second quarter, Eurostat reports paltry numbers for both the EU and the euro zone. The year-over-year GDP growth for the currency area was 0.6%, adjusted for seasons and inflation, and 0.7% for the EU as a whole.

Meanwhile, the raw growth number for the U.S. economy—adjusted for inflation but not for seasons—was 3.0%.

The preliminary numbers from Eurostat only report growth rate estimates for 13 of the EU’s 27 member states. Therefore, the numbers it presents—for the EU and the euro zone as well as for member states—should be read with some caution.

That said, these estimates are done with a high degree of statistical accuracy; any adjustments going forward will be minor. Therefore, we can safely use this number for a general assessment of the state of the European economy.

To begin with, it is embarrassing to, once again, have to report that Europe is not only failing to keep up with America but falling drastically behind. The fact that this is happening is even more perplexing given that the euro zone was formed in order to allow Europe to catch up with, compete against, and ideally surpass the U.S. economy.

That has never happened, and as these latest GDP figures show, it is not going to happen for a long time.

In the second-quarter numbers, only one economy can match the U.S. growth rate: Spain, which saw its inflation-adjusted GDP grow by 2.9% in the second quarter, year over year. Since the sample reported by Eurostat lacks 14 EU states, there are probably going to be a couple more countries that can match the U.S. GDP rates, but the overall picture of Europe is unmistakable.

It is a continent in economic stagnation.

Of the 13 sample countries reported, Spain is again the growth leader at 2.9%. Portugal comes in second at 1.5%, followed by Lithuania (1.4%) and Hungary (1.3%). France and Belgium mustered 1.1% growth, completing the list of countries that at least managed to expand their economies by 1% or more.

There was minor GDP growth in Italy (0.9%) and Czechia (0.4%), with Sweden and Austria at 0%. In Germany, Ireland, and Latvia the economies declined marginally.

It would be possible to dismiss at least some of these numbers if they came on the heels of stronger growth numbers from the first quarter. Unfortunately, this is not the case—Eurostat includes Q1 data for comparison, and they are about as bad:

Including the first-quarter figures paints an even more pessimistic picture of the European economy. Germany has now had two consecutive quarters with falling GDP, and even if the decline is marginal at -0.1% in both cases, it still means that German businesses produce less, German households make less money, and we can expect a rapid rise in German unemployment in the second half of this year.

With rising unemployment comes declining tax revenue; watch for urgent budget problems in Germany from hereon up to Christmas.

France has been lucky enough to have three quarters in a row with more than 1% annual GDP growth (1.3% in Q4 of 2023). However, that is really all there is to the French economy; growth rates in the 1.1-1.5% range are nowhere near what France needs to

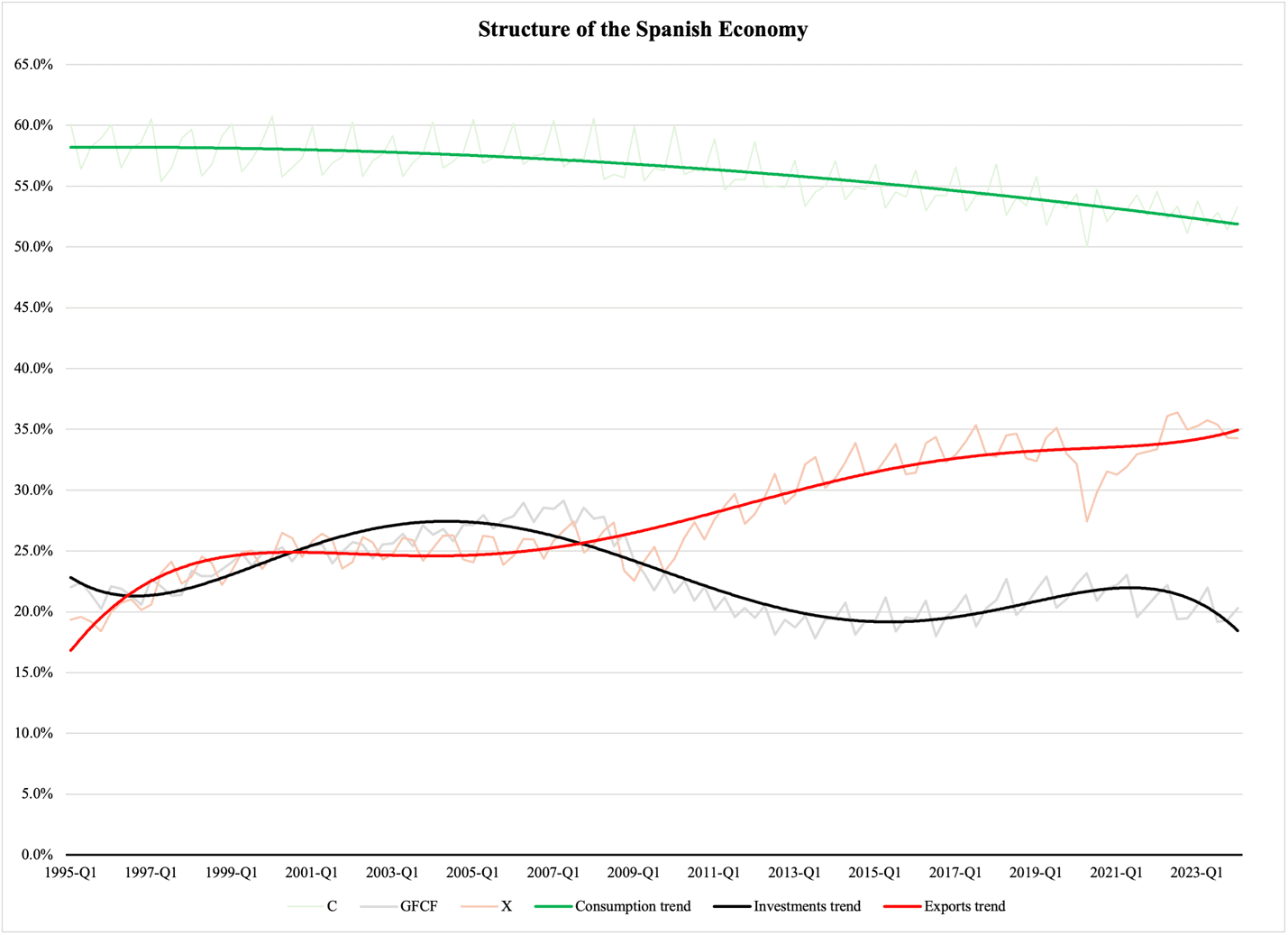

The solid Spanish growth rates raise the question of what is driving their economic expansion. Figure 1 reports trends in three key components of GDP: private consumption (green), gross fixed capital formation or business investments (black), and exports (red). These trends are reported as shares of inflation-adjusted GDP:

Figure 1

Since 1995, the Spanish economy has been through two major phases. Up to, approximately, the recession in 2008-2010, private consumption accounted for 55% of GDP or just above. During this phase, exports increased a bit initially but then stabilized at around 25% of GDP.

Business investments were solid, staying well above 20% and on occasion rising above 25%.

Before we continue, a note on arithmetic is in place. The calculation of GDP allows these three components to exceed 100%, i.e., technically become greater than GDP. The reason is that when we finalize the number for GDP, we subtract imports from exports. The statistical picture reported in Figure 1 only includes exports.

The reason for this is to illustrate what domestic economic activity contributes to the economy; imports do not contribute to, e.g., domestic employment, but exports do. Therefore, we can get a great deal of information on the current state of the Spanish economy by looking at the shift that happens when it transitions from phase 1—up to the recession 15 years ago—into phase 2.

From about 2010, exports increase their share of GDP; by 2023 it is at 35%. Meanwhile, private consumption slowly declines, contributing less than 55% of GDP and trending down toward 50%.

This tells us that the growth rates in the Spanish economy, which are high by European comparison, are driven entirely by exports. In short: the Spaniards are using more and more of their workforce and their domestic economic resources toward producing and selling goods and services to other countries.

There is a conventional wisdom among economists, and even more so among politicians, that a boom in exports is good because it has multiplier and accelerator effects on the rest of the economy. In short, it generates more growth by stimulating other domestic sectors. However, if this was true, we would see a rise in the investments share of the Spanish economy.

We do not see that. On the contrary, as the black line in Figure 1 shows, as a share of GDP, investments have dropped to the lowest levels they have been since at least 1995—and are even trending downward as a share of GDP.

In practice, this means that exports are growing much faster than business investments. In 2023,

What does this tell us? That the Spanish exports boom is not of the high-productivity kind. It is not creating well-paying jobs, and it is certainly not having any ‘proliferation’ effects on other domestic sectors. If it was, we would see a solid expansion in business investments.

Europe continues to fall behind America and other parts of the world. Its political leadership seems oblivious to this, which is more than a little worrying. With the exception of the dynamic economies along the eastern rim, from Estonia via Poland and Hungary down to Romania, the European Union is in a state of permanent economic standstill.

To be blunt: Western Europe is slowly morphing into an economic museum.