Boris Johnson has been one of the most divisive figures in Britain for decades. As the Brussels correspondent for The Daily Telegraph throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, he helped popularise Euroscepticism in Britain. Though widely ridiculed for his clownish behaviour, he achieved what seemed nigh impossible by winning two London mayoral elections as a Tory. His popularity in that role and in leading the Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum paved the way for him later to become the Conservative Party leader, after which he won a general election victory in 2019 which was as unlikely as it was decisive.

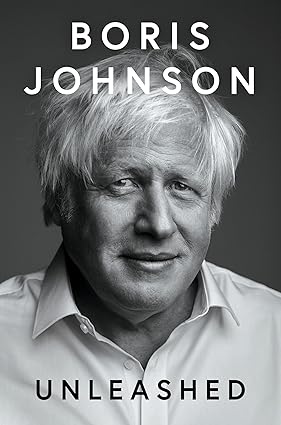

The prime ministerial memoir genre can often disappoint. Unleashed most certainly does not. Many things set Boris’s book apart. Unlike most politicians, he is a genuinely talented wordsmith. Some, blinded by their hatred of Johnson, fail to see the essential fact that he’s an extremely gifted communicator. The pages of Unleashed are lit up by the literary and historical references which are second nature to a classicist.

Ex-politicians often set out to avoid offending their old colleagues. Boris, typically, is immune to this, and wonderfully indiscreet. Baroness Hale, the former President of the UK Supreme Court, is likened to Shelob, the monstrous arachnoid from The Lord of the Rings. Theresa May is “old grumpy knickers,” and the Chinese lab workers who probably created COVID-19 are like the witches in Macbeth: “eye of bat and toe of frog … oops!”

He openly confesses to what are heretical opinions within the British Establishment, including that some part of him wanted Donald Trump to defeat Hillary Clinton in 2016. Reflecting on his tenure as UK Foreign Secretary, Johnson jokes that Kim Jong Un’s use of missiles called ‘Nodong’ may be an “unconscious revelation of the North Korean dictatorship’s phallic anxiety,” and elsewhere he speculates darkly that the desire by Theresa May to damage him contributed to the prolongation of a British prisoner’s unjustifiable captivity in Iran.

He is also more self-reflective than his detractors would believe. Johnson freely admits that his first few months as mayor of London were shambolic. Oddly, though he was only an opposition politician when the vote was taken to invade Iraq in 2003, Johnson dedicates a considerable amount of space to the issue. He was never enthusiastic about the invasion, he writes, and was quick to recognise this venture for the terrible error it was.

This book contains one of the most damning indictments of how Western hubris, following the Kosovo War, led America and its allies down a destructive path of interventionism and nation-building. The chaos of Libya following the deposal of its longtime despot in 2011 is described in some detail. “Killing Gaddafi,” Boris states pithily, “was a lot easier than replacing him,” and this fiasco showed that the British government and other states had learned little or nothing from Iraq.

Rather than expressing regret about the failure to act when the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad was on the ropes, Johnson states that there was never a clear route for how to successfully implement regime change. “Would it have been any better if we in the West had all launched an attack on him in 2013, and knocked him off his perch when he was most vulnerable? I don’t see any reason for thinking so. Iraq was a disaster. So was Libya. I can tell you categorically that we were equally clueless about how we might have replaced Assad,” he writes. This is worth bearing in mind when it comes to the foreign policy vision of European conservatives today and tomorrow, which should be guided by realism. Western democracy is worth fighting for, but it cannot be exported with military force.

The best of Johnson’s historical understanding and political judgement is shown in his clear-eyed assessment of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle. As well as drawing a sharp contrast between the success of Israel as an oasis of freedom and the political desert of the Middle East, he correctly identifies the main problem as being the unrealistic nature of Palestinian demands. Most importantly of all, he says something that should be obvious to any observer, but which is rarely stated by a Western leader: the key result of the Hamas onslaught on October 7th was to make the establishment of a Palestinian state virtually impossible.

The word ‘Boris’ will forever be linked with the word ‘Brexit.’ His decision to side with cultural conservatives in backing the Leave campaign in 2016 was absolutely crucial to that side’s victory. Without Johnson, the pro-Leave side would have been led by figures such as Nigel Farage who lacked a broad appeal to middle-ground voters. The then Prime Minister David Cameron readily understood this, which is why Boris says Cameron responded to his decision by saying that he would “f*** him up forever.” Johnson’s decision to get onboard the Brexit bus can be viewed as an example of moral courage or as an exercise in cynicism: perhaps Boris guessed that this particular red bus would transport him to Number 10 Downing Street faster than any alternative options.

Regardless of his true motivations, Boris’s second great sin against respectable progressive opinion was the manner in which he overcame the combined efforts of much of Britain’s political, social, economic, and cultural elite’s efforts to prevent the Tory government from actually taking Britain out of the EU. The ruling classes, Boris explains, “were struggling to adjust to the reality that they had appeared to have lost an argument to those that they had considered their intellectual inferiors.”

In a way that closely echoes the argument of Sir Paul Collier in his brilliant new book on regional economic inequality, Left Behind, Johnson views the Leave vote as being as much of a reaction against the power of London as it was a repudiation of the power of Brussels. Leave voters were “fed up with a system that seems to undervalue their own skills and their children’s skills because business can always supplant those skills from abroad,” he writes.

Whatever the merits or demerits of Britain leaving the EU—and it is difficult to sustain the view that the benefits heretofore have been worth all the disruption—the author deserves praise for one aspect of his leadership: Britain had voted to leave and that vote needed to be honoured … and without Boris, it probably would not have been.

His 2019 general election victory was a model in campaigning. By choosing the ‘Get Brexit Done’ slogan and relentlessly hammering it home, Johnson identified the key political fracture between traditional working-class Labour voters and that party’s leadership class which had grown to disdain their views on Brexit, immigration and much more besides.

Johnson’s skills as a communicator were never better utilised, the red wall was breached and the Tories picked up seats in numerous Labour strongholds. What is not adequately described by Johnson is the failure of his government to build on this progress to create a long-lasting Conservative majority. Immigration is a major part of what went wrong but is treated almost as a non-issue.

Brexit did indeed mean that immigration to the UK from the EU was no longer as easy, but the points-based system which Johnson’s government brought in did not slow the flow at all. It simply altered its source. Immigration soared, reaching a record level of 764,000 in 2022. More importantly, 91% of work-related migration that year was from non-EU countries, which were culturally far more different to the UK than, say, Poland. It is little wonder that so many British voters deserted the Tories then and later.

When explaining the emergence of a pro-Brexit majority nationwide, Boris quotes Chesterton’s poem entitled “The Secret People”: “Smile at us, pay us, pass us. But do not quite forget. For we are the people of England, that never have spoken yet.” On the topic of immigration, the secret people have spoken often, delivering a message that they want to decrease the pace of cultural change which has already left many people feeling like strangers in their own homeland.

Twice, in 2016 and in 2019, Boris Johnson chose to speak for those Chestertonian voters, but when he had the power to act on their behalf as PM with a large majority in Parliament, he quickly passed them by forgot about them. This speaks to a lack of seriousness which is his greatest failing.

Autobiographies often heavily feature the writer’s family. Not so with Unleashed. References to marital and family life are rare, probably not because Boris is naturally private. After a considerable amount of reading, Johnson Wife Number Two appears very briefly. After she has exited the stage without comment, Johnson Wife Number Three eventually appears. Various children are mentioned, but no answer is given to the age-old question: how many kids does Boris have exactly? It is not just that his romantic life has been noticeably … eventful. In writing about the riots of 2011, Boris blithely dismisses those who sought to examine root causes of unrest such as widespread family breakdown and the absence of male role models, dismissing such arguments as the work of “lefty criminologists.”

Johnson reflects that prior to Brexit he was thought to be “a pretty liberal kind of Tory” who could have gone to a “north London dinner party and not have been pelted with focaccia.” For example, he explains how he came to wholeheartedly embrace the Green agenda after initially being sceptical. He is not necessarily wrong about many of the environmental policies he has promoted (like promoting cycling or nuclear power), but he is clearly naive in drawing an analogy between Pascal’s wager and his belief in apocalyptic climate change, as if the steps required for achieving net zero will not come at an enormous economic cost.

It is little wonder then that when COVID came, Johnson was quick to jettison his libertarian instincts and embrace a harsh lockdown policy. A politician whose beliefs were rooted in greater moral or philosophical certitudes may have stuck to his guns, or at least had the good sense to obey the restrictions on socialising which he had forced on everyone else. Alas, Boris had no such spine or sense. He deserves credit for eventually reopening British society long before most other European governments took this step, but the damage caused to the economy by lockdown has been lasting.

In his concluding advice to conservatives, Boris urges future leaders to shrink the state and slash taxes, which immediately begs the question: why was more of this not accomplished during his own tenure? Unleashed is an absorbing and entertaining book that feels far shorter than its 784 pages. What lessons should Europe’s conservatives derive from studying Johnson’s career? Clearly, one does not have to be from a working-class background to appeal to working-class voters: authenticity can actually be an advantage so long as a politician listens to their target audience and lays out a clear and comprehensible vision for what should be done. In today’s dynamic and fast-changing world, no region—be it the Labour stronghold of London or the Labour heartland of northern England—is necessarily hostile terrain for those who are right-of-centre.

There is an element of the Shakespearean tragedy to Johnson’s political career: the hero being destroyed by his fatal flaw, with awful consequences for those around him. But this is ultimately too harsh a lens through which to view him. Boris committed no great crimes: he did not murder his monarch or leave the realm in rack and ruin. A more apt way of assessing his time in public life is to look to Shakespearean history, and think of an alternative reality in which Falstaff somehow became King, surprised everyone at court by his initial accomplishments, before inevitably losing the crown and ending up back in the tavern once more.

The concluding section of his memoirs shows that Boris clearly regrets the missed opportunities and what could have been achieved had he remained in Downing Street for longer. Conservative Britons should regard the time he did have in Number 10 as a great missed opportunity of all.