The tomb of St. Pius V at the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome depicts some central episodes of his pontificate. On the left of the monument, we see Pius V, seated on his throne, handing the banner of the Christian fleet to Don Juan of Austria (1547-1578), the victor of the Battle of Lepanto. In the bas-relief on the right, the Pope hands the captain’s staff to Count Sforza di Santa Fiora (1520-1575), the victor over the Huguenots in France. Above the statue, in the centre, is depicted the coronation of the Pope, while in the two smaller panels on the sides are represented the victory of Lepanto and the victory against the Huguenots.

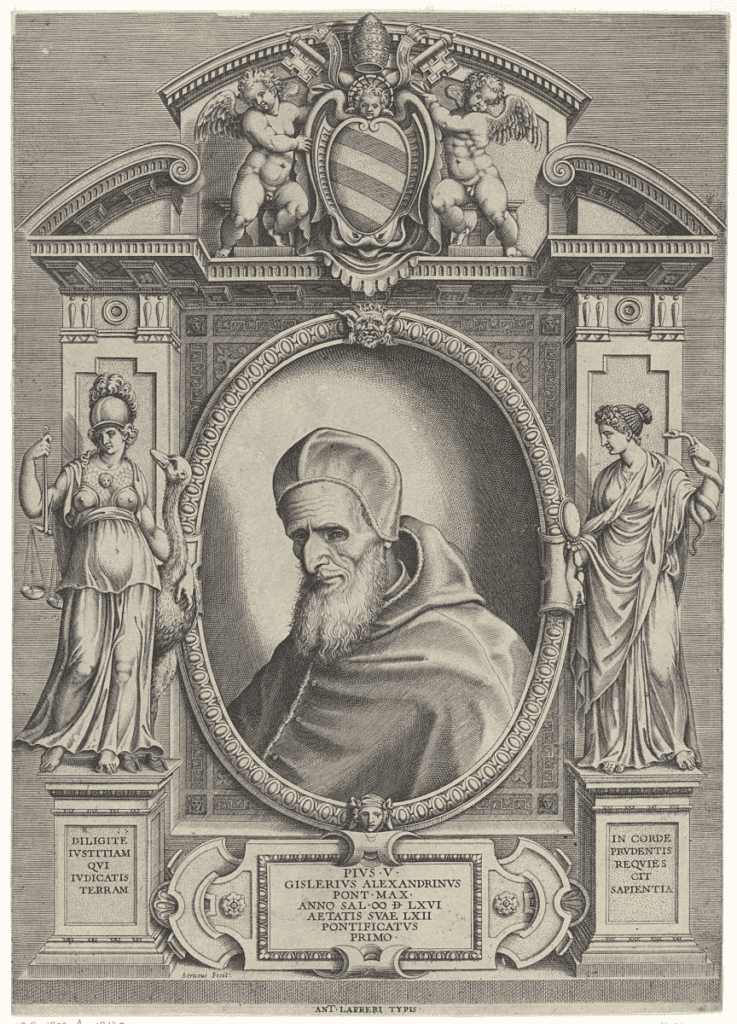

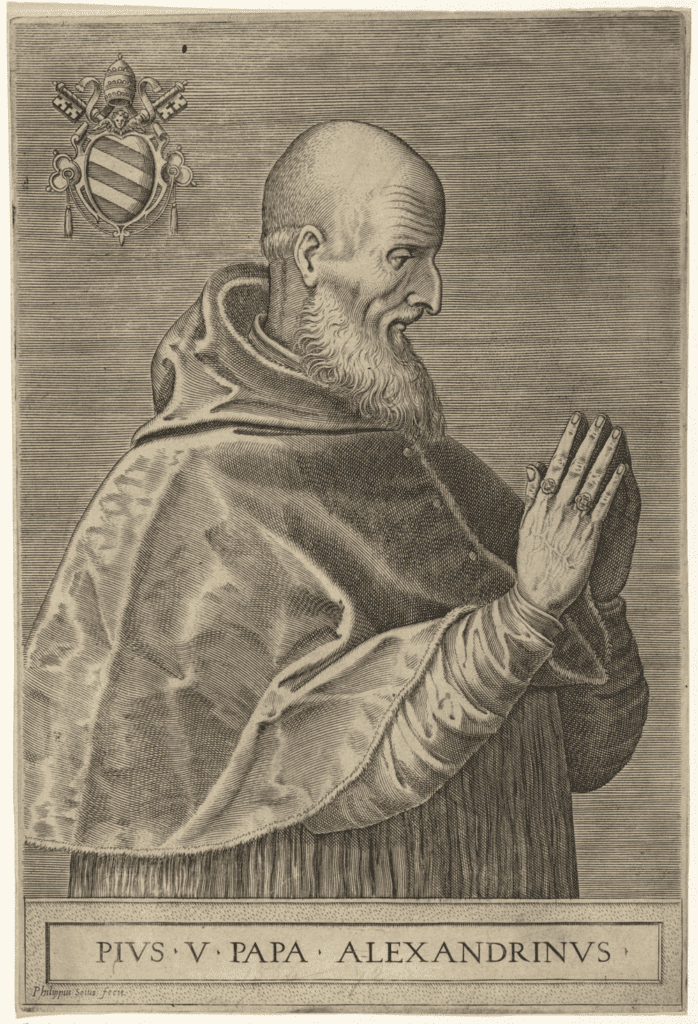

The defence of Christendom against the Turks—together with the fight against heresy—was a dominant feature of the pontificate of Pius V (1566-1572). In the second half of the 16th century, Islam had reached the apex of its expansion from the Red Sea to Gibraltar, from Baghdad to Budapest, reaching the gates of Vienna. The main architect of this expansion was Sultan Suleiman I (1495-1566), known as “the Magnificent.”

In the second half of the 16th century, Islam had reached the apex of its expansion from the Red Sea to Gibraltar

The coasts of the Mediterranean were devastated by the raids of the Barbary corsairs who were looking for women for the harems of the viziers and men to be sold as slaves or to be enlisted in the Janissaries, the private army of the Sultan. The ultimate goal of the Turkish conquests was the “Red Apple” (Kizil-Elma), which referred to the golden globe, surmounted by a cross, held by Emperor Justinian in a giant statue that formerly stood outside the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. After the conquest of that city in 1453, Rome, the city of the Popes, became the “Red Apple”—i.e., the final objective of the Ottomans and the would-be symbol of the triumph of Islam over Christianity.

Pius V was aware of this symbolism and, since his election, he understood that only a preventive war against the Turks could save the West. With grave and moving words, he exhorted the Christian powers to unite against the aggressors, making the defence of Christianity the axis of his brief pontificate.

In 1566, the year of the ascent of Pius V to the papal throne, Suleiman was succeeded by his son, Sultan Selim II, who decided to break the peace with Venice, claiming alleged rights on the island of Cyprus, a Venetian colony that remained, with Malta, the only Christian enclave in an Ottoman Sea. Venice prepared for war and, in this conflict, Pius V saw an opportunity to realize his goal: the formation of a league of Christian princes against this enemy of the Catholic faith.

It must be said that the expansion of the Turks was also facilitated by the decisive complicity of certain Christian countries—such as France, which, in the name of realpolitik, encouraged and financed the Ottoman Empire in order to weaken its traditional enemy: the House of Habsburg. Nevertheless, thanks to the prayers and insistence of the pontiff, the treaty forming the League was signed on May 20, 1571, by representatives of the Pope, King Philip II of Spain, and the Republic of Venice.

Pius V was the true author of the Holy League

The specific clauses of the agreement forming the alliance established that Pius V, Philip II, and Venice all declared war on the Turks to recover all the ground they had usurped from the Christians— including that of Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli. At the head of the Christian League was placed a young 25-year-old man: Don Juan of Austria, the biological son of Charles V and therefore the half-brother of Philip II.

The Italian historian Luciano Serrano, who has dedicated a well-researched study to the origins of the treaty, writes that Pius V was the true author of the Holy League: “He proposed it, stipulated it, and gave it consistency, dedicating to it the deepest energies of his spirit and the sacrifices and prayers of his most holy life.”

The coalition against the Turks was not only defensive in nature but also offensive, insofar as Catholic morality allows. The Pontiff was convinced that there would be no truce with Islam until the Ottoman Empire was completely annihilated. On May 27, 1571, in St. Peter’s Basilica, Pius V, in the presence of all the ambassadors, announced the birth of the Holy League to the Roman people and promulgated a universal jubilee to draw the blessing of God upon the Christian army.

On August 14, in the Church of Santa Chiara in Naples, Cardinal Granvelle presented Don Juan of Austria, on behalf of the Pope, with the captain’s staff and the sacred banner of the Holy League. The banner was of blue silk damask, with the image of the crucified Saviour, at whose feet were the coat of arms of Pius V, on the right those of Spain, and on the left those of Venice. The papal fleet was commanded by Marcantonio Colonna, Duke of Paliano, to whom the Pope entrusted the flag of the Church: a red damask banner with the image of the Crucifix, and St. Peter and St. Paul on the sides, with the motto: “IN HOC SIGNO VINCES.”

The churches of all Catholic countries resounded with a Te Deum of thanksgiving

That day, in Rome, around at 5:00 pm, Pius V was discussing business with his treasurer, Bartolomeo Bussotti. Suddenly, the Pope interrupted the conversation, got up, approached the window, and stayed there for some time, as if contemplating a mysterious scene. Then, visibly moved, he returned to his treasurer and said: “Let’s not talk any more about business. It’s not time for that. But let us go and thank God because our army has won a victory at this moment.” Then he dismissed the prelates and went immediately to the chapel, where a cardinal found him weeping with joy. Treasurer Bussotti and his colleagues faithfully noted the day and hour when the Pope had made this statement, which was confirmed 15 days later by the arrival of a courier with news of the great victory.

On September 16, 1571, the Christian fleet left the city of Messina, where it had gathered, and advanced towards the enemy. The clash with the Turkish fleet took place at noon on October 7 in the waters of Lepanto, at the entrance of the Gulf of Patras. The battle was formidable, given the number of men and galleys deployed on both sides, as well as the sheer intensity of the fighting. After five hours of furious combat, the incredulous Christians were assured of a complete victory. Miguel de Cervantes, travelling on a Spanish galley, defined the event as “la mayor jornada que vieron los siglos” (“the greatest day that the centuries ever saw”). The name of Lepanto thus entered history.

The Pope, later awakened in the middle of the night, again burst into tears of joy and pronounced the words of old Simeon: “Nunc dimittis servum tuum Domine … quia viderunt oculi mei salutare tuum” (Now let your servant, O Lord, go in peace …. go in peace … because my eyes have seen your salvation) (Luke 2:29-30). At dawn the next day, the ringing of the bells and the singing of the Te Deum announced the victory to the Roman people.

Paolo Veronese dedicated two magnificent paintings to the Battle of Lepanto, one located in the Accademia in Venice and the other in the Palazzo dei Dogi. Titian, then 95 years old, created an allegory of the memorable event for Philip II. Another famous “Allegory of the Holy League” was commissioned of the painter El Greco by Philip II.

The churches of all Catholic countries resounded with a Te Deum of thanksgiving. In the commemorative medals that he had minted, Pius V placed the words of the Psalmist: “The right hand of the Lord has done great things, from God this comes” (Psalm 126). The Venetian Senate also wanted to attribute to the Holy Virgin the main merit of the victory and on the picture painted in the hall of his meetings they placed the words: “Non virtus, non arma, non duces, sed Maria Rosarii, victores nos fecit.”

In fact, Pius V attributed the triumph of Lepanto to the direct intercession of the Virgin and ordered that the invocation, “Auxilium Christianorum, ora pro nobis,” be added to the Litany of Loreto, setting October 7 as the feast day in honour of Our Lady of Victory. His successor, Gregory XIII, instituted the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary and later, in 1716, Clement XI, after the victory of Prince Eugene of Savoy against the Turks at Petervaradino, extended it to the whole Church.

It is interesting to note that the German historian Don Hubert Jedin (1900-1980) devoted an extensive study to the Holy League and the idea of ‘crusade’ in the thought of Pius V. According to Jedin, the League was not just any treaty between States for the Pontiff, for with it one of the greatest ideas of the medieval Papacy had been renewed. Although Pius V never used this term—perhaps because it was by then reserved for the indulgence valid in Spain—there is no doubt that the idea of a santissima expeditio was conceived and promoted by him in 1570 and fully corresponds to the traditional concept of a crusade. The concept of a crusade in the mind of Pius V was an “offensive” action that, Jedin tells us, “is detached in principle both from that of the Republic of San Marco and that of Spain, both of which were based on a defence of their own territorial and maritime situation.”

Although he sent no Papal Legate to the Christian fleet, Pius V considered himself the true head of the Holy League, since he still felt himself as the head of Christianitas and considered it as such. “The league of 1571,” Jedin reiterates, “was conceived by the Pope as the beginning of the enterprise of a crusade; it was placed under the idea of a crusade.”

The flag raised by Marcantonio Colonna on the waters of Lepanto is the same vexillum Sancti Petri that was waved on the fields of the crusades. It is the flag of the Church, whose form varied but whose colour always has been red and on whose background always stood the image of the Crucifix (or the keys of St. Peter). “If medieval insignia indicating sovereignty express much of the ideal characteristics of medieval sovereignty,” Jedin writes, “this is also true of the banners under which the League fought at Lepanto.” He continues:

The crucified Christ is not merely an image of Christ but the cross of the crusaders: Peter and Paul symbolize not only that Colonna commands the papal contingent but that the Roman Church and its head, the Pope, identify themselves with the enterprise. The motto IN HOC SIGNO VINCES shows how the war is a war of faith.

On November 17, Pius V informed the King of Portugal that he intended to extend the war against the Turks to the Kings of Ethiopia and Persia, and to other princes of the region. The Pope wrote to Shah Tahmāsp I, Seriph Mutahar King of Arabia Feli, and Menna King of Ethiopia to urge them to take up arms. This decision demonstrates the broadmindedness of the Pontiff, who was willing to ally himself not only with the Orthodox Tsar of Moscow but also with the Scythian Muslims of Arabia against the Sunni Ottomans—for the good of Christendom.

the name of Pius V remains inextricably linked to the triumph of Lepanto

On February 10, 1572, the Holy League was renewed in the Vatican by representatives of Philip II, the Republic of Venice, and Pius V. In a long declaration on March 12, 1572, addressed to all Christendom (Universis et singulis Christifidelibus), Pius V called for the war against the Turks to continue, and he granted to all who took up arms or contributed with money to the war the same indulgences that, in the past, had bought the crusaders. The goods of those who left for war would remain under the protection of the Church.

But just in those days, the bishop of Dax François de Noailles, ambassador of Charles IX, was arriving in Istanbul—with the mission of obtaining peace between Venice and the Ottoman Empire in order to isolate Spain. This “nefarious peace” between Venice and the Turks marked the end of the Holy League.

There were efforts—all in vain—made by Pius V’s successor, Pope Gregory XIII, to keep the spirit of Lepanto alive. Pius V’s great dream was to restore religious and political peace to Christendom by destroying its internal and external enemies. But Divine Providence had arranged for his project to remain unfulfilled. Yet, to this day, the name of Pius V—whom Cardinal Georges Grente (1872-1959) called “the Pope of the great battles”—remains inextricably linked to the triumph of Lepanto.

This essay appears in the Fall 2021 edition of The European Conservative, Number 20: 66-69.