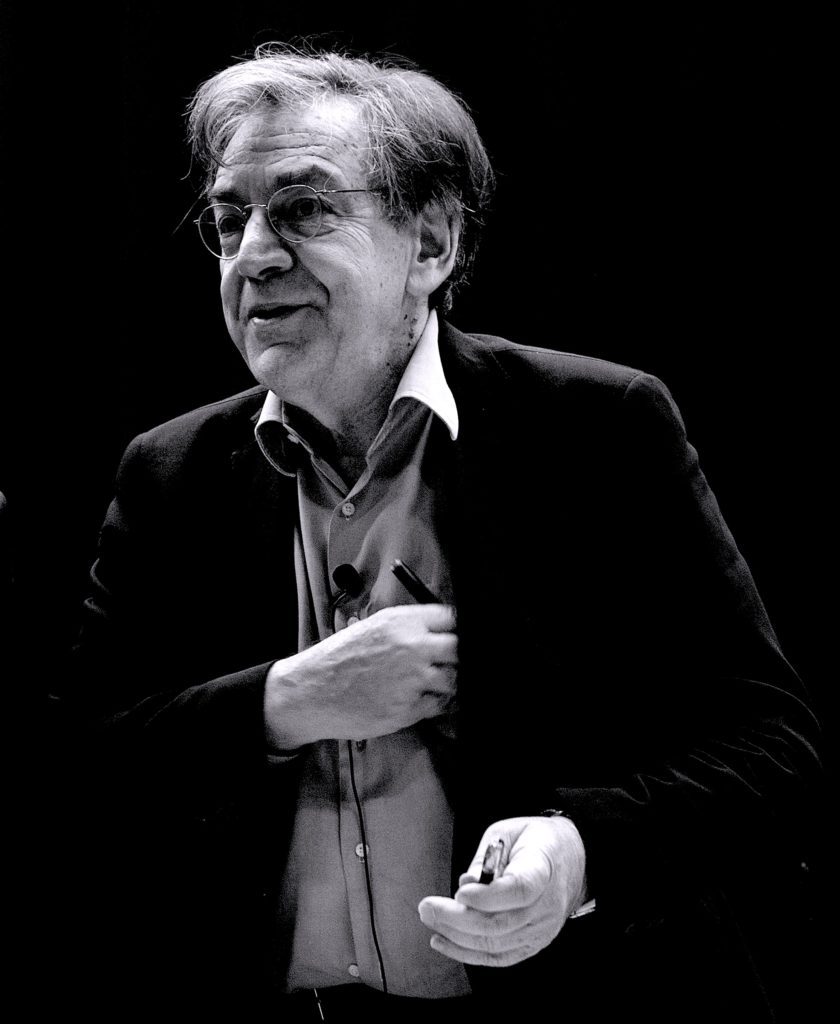

PHOTO: JÉRÉMY BARANDE / ECOLE POLYTECHNIQUE UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SACLAY / CC BY-SA 2.0.

The ‘trigger warning’ system in France just about melted down: “Rape! Rape! Rape! There you go! I say to all men: rape women! In fact, I rape mine every night. Really, every night. She’s so sick of it.” This burst of angry sarcasm came from Alain Finkielkraut, France’s most eminent ‘un-woke’ intellectual, on November 13, 2019. He was responding to feminist activist Caroline de Haas’ unhinged accusation that he was “banalizing rape” by defending filmmaker Roman Polanski. (Polanski was then facing yet another round of accusations despite already having been convicted in the 1970s of the statutory rape of a 13-year-old model.) Finkielkraut’s ironic rejoinder to Haas was to simply ‘double down.’

The Twitter clips of Finkielkraut’s rant instantly went viral. There he was—one of France’s most decorated men of letters and a member of the august Académie Française—apparently urging men, on air, to mercilessly rape women.

Afterwards, Finkielkraut emerged largely unscathed from the alleged ‘hate crime’ lawsuit brought against him by the usual plethora of left-wing NGOs. But their complete inability to detect the (perhaps overdone) irony of his comments speaks to a deeper societal malady—one that Finkielkraut himself has diagnosed in his latest book, L’Après Littérature (2021). Is France—the homeland of much of the West’s greatest works of literature—becoming a rigid ‘literal society’ in which all statements and all words are to be construed literally?

In several ways, the crisis of culture has been an enduring theme throughout Finkielkraut’s four-decades-long literary career. He entered the intellectual fray in a fit of disavowal—by breaking with the progressive activism of his formative years at the prestigious Henri IV preparatory school and the École Normale Supérieure. “Love isn’t amenable to revolution,” he had written in his first essay, co-authored with his classmate Pascal Bruckner. Later, in Le Nouveau Désordre Amoureux (1977), he inveighed against the sexual liberation movement and its intellectual patrons, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, accusing them of disenchanting love and erasing “sexual voluptuousness” in their effort to eliminate or ‘flatten out’ gender differences.

However, Finkielkraut’s fissure with the ideas of Mai 68—in which he had partaken as a militant Maoist—runs much deeper. If a neoconservative is a liberal who’s been mugged by reality, then a nouveau philosophe—that is, a member of the loose intellectual grouping to which Finkielkraut has always been closely affiliated—is a Jewish intellectual who fell out with the Left over the Yom Kippur War. Indeed, it was in the mid-’70s that Finkielkraut began his gradual distancing from every Leftist piety espoused by France’s cultural intelligentsia.

To the extent it has mattered to his career, Finkielkraut’s Jewish identity has cast him as a suitable and ‘friendly token’ from a favored minority—that is, until the rise of anti-Semitic Islamo-leftism made it a liability. Finkielkraut had already sounded a prescient alarm about this strain of anti-Semitism in the early 2000s, during the Second Intifada. Earlier on, his essay Le Juif Imaginaire (1981) stood out as a most thoughtful reflection on the post-war Jewish condition à la Albert Memmi, the famed Jewish French-Tunisian writer.

Finkielkraut—the son of Holocaust survivors who had emigrated from Poland in the 1930s and had become French citizens in 1950—has previously reported feeling uneasy about “benefitting” from his Jewishness amid collective European guilt over the Holocaust, without ever suffering discrimination himself. But that all changed when the new generation of sons of Muslim immigrants in France gave anti-Semitism its new face. In fact, during the gilets jaunes protests in Paris in February 2019, protestors were caught on video yelling expletives at Finkielkraut as the writer returned home from a daily walk. “Dirty Zionist! France is ours!” one yelled at him. By that time, of course, Finkielkraut’s reactionary turn was all but complete.

In a France where upholding republican values increasingly requires foregoing one’s collective identity, this embrace of Jewish particularism sits uneasily with Finkielkraut’s professed republican universalism. And yet if one shibboleth emerges from the more than forty titles Finkielkraut has published in nearly 45 years, it is his defense of high culture and French education as an instiller of republican values.

The decay of mainstream culture was already the theme of his La Défaite de la Pensée (1987), but his latest 2021 essay goes much deeper. “We live in the age of post-literature,” he writes. “The times when a literary vision of the world had a place in the world now seem remote.” Two authors stand out in this latest requiem for literature. First, there is Milan Kundera, the Paris-based Czech author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1982), who is credited for Finkielkraut’s taste for ambiguity—that is, for problems not easily resolved and choices not easily made. This is a clear departure from the idealism of Finkielkraut’s youthful years.

Then there is Philip Roth, in whom Finkielkraut sensed an omen of our own political future. Reflecting on Roth’s The Human Stain—the 2000 novel about a light-skinned African-American professor named Coleman Silk who is wrongly accused of racism—Finkielkraut writes: “[T]he antiracist spirit blowing through U.S. college campuses at the turn of the millennium does not sound the death knell of racism, but rather continues it.” Indeed, in ‘wokeness’ (in French, l’éveillement), Finkielkraut senses a grave danger. In fact, he has been dedicating increasing airtime and commentary to this phenomenon in his highbrow radio show, Répliques. He also sees it as a noxious import from America—one that conflicts with the founding values of the French Republic. “There is in wokeness a vertigo of moral superiority,” he told Europe 1/Les Échos/CNews in a recent hour-long interview, “an arrogance of the present.”

In another life, Finkielkraut the literary exegete would have sat out this political tussle, content with simply lamenting the breakdown of the arts and letters from the sidelines. Yet wokeness has now infiltrated mass culture and has corroded the life of the mind. Finkielkraut simply cannot afford to let such forces prevail—not if literature is at stake—nor can the rest of us.