Alexandre Lacassagne, the French forensic pathologist who published a book on tattoos in 1881, would have been astonished at, and puzzled by, the explosion of elaborate and professional tattoos in the general population in the last three decades.

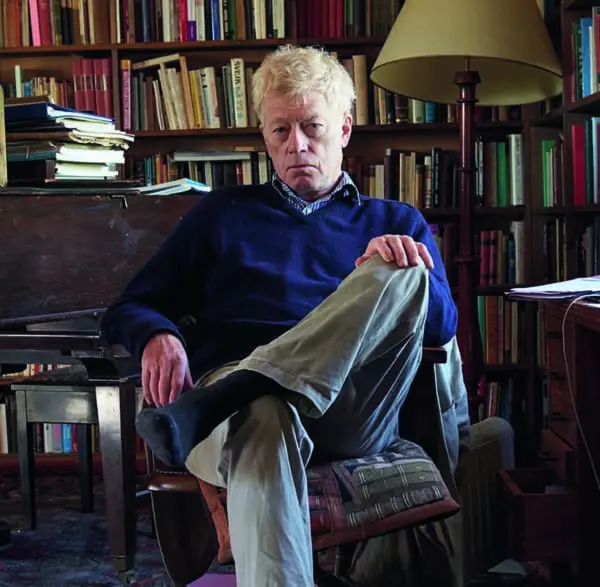

Roger Scruton never sought fame as a philosopher, much less as an academic. From the age of sixteen, as he put it to me, his one ambition was “to be like the great characters whose works I was reading.” That is why, as a student at Cambridge, he resolutely declared: “I must be a writer—that is the thing I must be!” However, as he noted in the book that we produced together, Conversations with Roger Scruton, he initially found writing “very difficult.” Hence, he adopted the “Protestant view that nothing works like work, and if you’re not succeeding, you must try again.” He reflected, “I didn’t have innate talent. I’m not a spontaneous, creative person; I do, however, have a capacity to work and an ability to synthesise things … in a single thought.” For Roger, that was something which came “partly through journalism.”

With Bloomsbury, I have recently published Against the Tide: The Best of Roger Scruton’s Columns, Commentaries and Criticism. It is a collection of Roger’s journalism spanning almost 50 years, from his first piece on Michel Foucault in The Spectator (1971), to his last diary entry in the same magazine just prior to his death in January 2020. I had two reasons for assembling this volume. As I remark in the Preface, this was something Roger and I spoke about in our last conversation. Addressing me as his literary executor, he lamented the fact that his early columns were no longer available to readers. And so, I resolved that I would retrieve the best of his old columns and showcase them alongside his more recent output. Second, however, I wanted to highlight the fact that a significant part of his legacy, perhaps as important as his philosophy, was his political and social commentary. For it is in this that we see Scruton, not so much the academic or philosopher, but as the thing he spent his lifetime becoming: a man of letters.

If journalism helped him to synthesise ideas in a single thought, it also displayed the rich literary gifts which first brought him to the attention of the British public in the 1970s. For him, journalism was much more than conveying information, news, or opinion. It was an attempt to stir the imagination of the reader so that the ‘unfashionable opinion’ being expressed might become theirs. This is why, as he explains in Conversations with Roger Scruton, “craft really matters.” It is not enough to bombard readers with an unpolished polemic. The only thing that will win their favour and elicit their sympathy will be a work of art. Indeed, that was a principle to which Scruton strongly subscribed in all his published writing, which is why he forever bemoaned the fact that he was not widely viewed as a man of letters—a writer rather than a professional philosopher. Of course, he was a brilliant philosopher, but philosophy was but one medium through which he conveyed his ideas. As important to him, if not more so, were his journalistic works and his fiction.

This explains why Scruton greatly admired Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre, he said, “was able to imbue the world with his own spirit and to make it look back at him in a confirming way.” Such thinkers are, for Scruton, “real philosophers” in that they are “people who make philosophy continuous with the life of the imagination.” There was, he said, “nothing affirmative in Sartre, but there was, nevertheless, the imaginative endeavour to present what life is like ‘to me, Jean-Paul Sartre.’” In everything that Scruton wrote, he, too, sought to make philosophy continuous with the life of the imagination. Hence, in each of the columns I selected for Against the Tide, we see a philosophical vision conveyed in writing that is as beautiful as it is persuasive.

Take, for example, his column from 1984 entitled “The Art of Motor-Cycle Maintenance.” Originally published in The Times, where Scruton was a columnist from 1983-1986, this piece sat seamlessly alongside those dedicated to castigating the enemies of Mrs. Thatcher, or those critical of Western pundits and politicians who sought to justify the Soviet Union. “People need things, almost as much as things need people,” Scruton reflected later.

The critical moment of their mutual support is the moment of breakdown. Suddenly, the object on which everything depended—the car, the boiler, the drain, or the dinner suit—is unusable, and you contemplate its betrayal in helpless unbelief. It is some time before you overcome your self-pity enough to recognise that its need is greater than yours.

Scruton was not yet 40, but this piece is so resonant of the ‘later Scruton’ that it could well have been written in the last years of his life. Beautifully composed, rich in imagination, and with a tender voice, it does in one paragraph what it took Martin Heidegger an entire section of Being and Time to accomplish. Most of those reading this column in 1984 would have had little, if any, philosophical training. Yet, the idea that people and things are mutually dependent was made perfectly clear to them in just a few lines. Again, this is why ‘craft really matters’: without the imaginative power of high-quality writing, Scruton’s voice would not have been heard beyond the parochial precincts of the university, or perhaps beyond a partisan public in search of polemics that reinforce prejudice. It is true that Scruton held deeply conservative convictions and that, particularly in his early years as a journalist, he often used polemic to denounce objectionable causes. He never did so, however, without arguing his case rationally, coherently, and always with a touch of graceful humour.

When, in 1985, he took on a “weatherhen of liberal sentiment” who defended “the view that teachers should not strike,” he did so in classic Scruton style:

In truth, it seems to me, neither the teacher nor the nurse has a special responsibility. If two people bring a child into the world, then it is their duty to look after him. If the state provides him with an education, then the parents receive a privilege. However, when teachers withdraw their labour the privilege expires, and parents must bear the full burden of a responsibility which is in any case wholly and immovably theirs. If they have to give up work in order to look after their children, that is what they ought to do. If it is a hard thing to do, that is because life is hard. But those who have children must expect on occasion to pay for this most comforting of human afflictions (from “In Loco Parentis,” The Times, 1985, reproduced in Against the Tide.)

This is not an attack on working parents, but neither is it a wholesale defence of teachers. Earlier in the piece, Scruton opposes the idea that teachers have a ‘right’ to strike because, he argues, a strike “is a conspiracy to frustrate the aims of a contract.” However, he is swift to concede that teachers and nurses “are as entitled to strike as anyone else. The fact that they do not is testimony only to the conscience engendered by their profession.”

If anything, Scruton’s “In Loco Parentis” seeks to persuade parents to assume responsibility for their children, and to explode the “perverse logic of the welfare state” that “the teacher becomes a father to children who are not his own.” That Scruton argued for this in carefully crafted language devoid of cliché and caricature meant that it reached its target in a spirit which challenged without giving insult. It was powerful yet disarming; tasteful and yet a little spicy.

Similarly, in a piece penned for the Daily Mail in 2006, Scruton responded to the broadcasting of inflammatory cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. He asks: does “the understandable fury these cartoons have elicited mean that they should never have been published or broadcast?” His thoughtful answer was one of the most significant in that debate, and certainly not one which his detractors could dismiss as right-wing bigotry. It was wrong, he said, “to publish and broadcast cartoons that every Muslim will find offensive,” yet it was also “understandable.”

For we cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that the London suicide bombers were Muslims who saw themselves as mujahideen, advancing the cause of their faith. If a Christian were to blow innocent bystanders to smithereens as part of a crusade against the heathen, no doubt we would see cartoons of Christ with a fuse attached, and crosses turned to daggers. Christians, too, would find this offensive.

However, “if you respect the icons, the rituals and the sacred texts of another person’s faith, you can raise even the most intimate questions as to the truth of its moral record without causing offense.”

If, as I believe, this is Scruton at his finest, it is because in one small article he cuts through the hysteria and offers, in language that is almost prayerful, a solution that seemed to elude commentators across the spectrum.

Politeness and decency are, second nature to anyone truly brought up on the teachings of the Koran. So are other virtues that we are losing in modern Christian societies: respect for the sacredness of life, temperance, the care of the elderly and family values. The decline of the Christian faith in this country has gone hand in hand with the loss of those values. And this is one reason why Christians need to debate their faith with Muslims, to understand where they differ and to rediscover the virtues they share.

Hence, Scruton continues, “draconian laws such as the ragbag Race and Religious Hatred Bill” will merely tempt us

to see jihad written over every Muslim face, and Muslims will see moral ignorance written over the faces of those who do not share their faith. The remedy for this is not to outlaw discussion but to promote the courtesy that makes discussion possible.

Language matters, but it seriously mattered to Roger Scruton. He understood that the way something is said often matters more than what is being said. That is why, as he grew older, Roger rarely wrote without draping his words in a garland of grace. His beautiful prose became his trademark and earned him the approval of both friend and foe. His writing revealed a sensitive and deeply spiritual individual seeking to make sense of a world to which he was increasingly becoming a stranger. He was—to adapt the title of his book of short stories—a soul in the twilight.

This, however, did not detract from his talent as a great comic writer, something which shines through at many points in Against the Tide, but which sparkles when he turns his pen to questions of the natural order. “How should we deal with nasty animals?” he inquires in a piece from 1991 for the Los Angeles Times. Nasty animals are those

which do not bite and kick continuously. They often brood about their captive state until the day comes for revenge. The pit bull terrier, for instance, will behave impeccably for years before suddenly killing his keeper, an outcome that may be welcomed by everyone else. Unfortunately, he will usually try to kill everyone else as well.

Roger Scruton was a serious and thoughtful man, but he was also a comic genius who, even in his last days, saw the humour in everything. When I went to spend what would be our last weekend together, I was surprised to find my friend defying adversity by cracking jokes. Even then, in the dark gloom of a winter’s night, and in the face of all that stood against him, he had me in hysterics of laughter. Nothing could prevent him from softening the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune with a smile.

To the very end, he looked at life with a hesitant grin, often mocking the very existence which he had made his own. Few philosophers laugh at other philosophers, simply because most philosophers do not know how to laugh. Roger, however, was not one of these. About Kierkegaard, he wrote “Fear and Trembling, The Concept of Dread, The Sickness unto Death—what kind of guy writes books with titles like that, and doesn’t ever sign them with his own name?” And, with even more fatal satire, he took aim at Edmund Husserl:

Husserl began his philosophical career with an attempt to make sense of mathematics, and made nonsense of it. He went on to invent the science, or pseudo-science, of phenomenology, believing that there was a method whereby he could isolate what is essential in our mental contents by ‘bracketing’ the material world. The reams of inspissated prose that this produced ought to have alerted Husserl to the fact that he was describing nothing at all. But no: he merely invented a ‘crisis of the European sciences’ in order to explain it. Unknown to himself (and self-knowledge was the first victim of this obsessive study of the self ) Husserl was that crisis.

No one ever made me laugh like Roger Scruton. But his sense of humour was matched by his profound reflections on the transcendental, the sacred, and the tragic. He was a philosopher, a writer, a gifted musician, a novelist, a journalist, and a farmer whose writings on the land resemble whispered secrets from absent generations. Indisputably, he was what he always aspired to become: a man of letters. My hope is that Against the Tide provides not only ample proof of this, but is a testament to one man’s enviable ability to put language at the service of the good, the true, and the beautiful—even when, as so often in our world, these have been consigned to silence.