I would like to venture an uncontroversial definition of freedom: It means being able to do what you want to do. By this definition, most of the West is unfree. Consider the young, who are the most transparent mirrors of our present culture. They fear death—even the slim possibility of death from COVID—more than my generation feared nuclear holocaust. In their risk-averse careerism, they dread one stray B grade on a university paper, which they are convinced will derail their progress toward career and success. It’s a strange anxiety when compared to my grandparents, who faced extreme financial uncertainty while raising entire families during the Great Depression. We’ve seen liberation after liberation since the 1960s. But the rising generation doesn’t feel that it can afford the luxury of freedom.

In this regard, we are in the condition St. Paul ascribes to himself. “I do not do what I want,” he says in the seventh chapter of his Letter to the Romans, “but I do the very thing I hate.” Few are entirely captive in this way. Most of us do some of the things we genuinely want to do, and we can avoid being under the complete command of what we hate. But the trajectory of our societies is negative. Whether it is the threat of being canceled or anxious concerns that we’ll lose out in the meritocratic race for success, we’re more and more enslaved and less and less free.

We’re in this pickle because we’ve lost sight of the true sources of freedom, which come not from permission but instead from commitment. To regain a true understanding of freedom, I propose that we turn to the Bible, as well as the wisdom of the Jewish tradition.

In the New Testament, an important expression of freedom is parrhesia, which means frank or candid speech. St. Paul appeals to this kind of freedom in his First Letter to the Thessalonians. At the outset of the second chapter of that letter, he digresses to underline the reasons why those in the church in Thessalonica ought to give credence to his witness and that of Silvanus and Timothy, his fellow missionaries. He points out that they have nothing to gain from what they say. On the contrary, in Philippi they were ill-treated. Paul notes that he and his comrades speak plainly and without guile. They do not flatter their audience, nor do they seek honor and acclaim. As Paul reminds them, while preaching they worked to provide for themselves, showing that they were not “selling” the gospel for their own benefit.

In this list of reasons, Paul is making a claim about freedom. We would do well to heed it today when freely expressing our views seems difficult. The Apostle is not fearful of death or imprisonment. He is not in the thrall of a psychological need to be liked or honored. Concerns about his material well-being do not control what he says. Simply put, underlying his frank and candid speech is a spiritual freedom, a freedom from worldly powers that seek to dictate to us what must and must not be done.

An episode early in the Acts of the Apostles offers another example of spiritual freedom. After Pentecost and the descent of the Holy Spirit, Peter began preaching in Jerusalem. Accompanied by John, he went to the Temple, where they spoke to priests, soldiers, and ordinary people. This disturbed the religious authorities, who in effect called them into the principal’s office for discipline. But instead of acting meekly, Peter told them that the gathered luminaries of Jerusalem, the builders, had rejected Christ, the cornerstone. Those in authority marveled at the boldness of such words—and in the New Testament, it’s the word parrhesia that is translated as boldness. The blunt words disturb the high priests, for they see that Peter and his comrades are uneducated men, “common men,” as the New Testament puts it. One can imagine the religious authorities, men of education and high standing, remarking to each other, “What do these nobodies think gives them the right to preach and teach of the high things of God?” And so the religious council charges them to be silent and threatens punishment if Peter and John are caught speaking so boldly again.

Of course, Peter and his comrades do not remain silent. They immediately recommence their public teaching, and, as the New Testament reports, “many signs and wonders were done among the people.” This outrages the religious authorities in Jerusalem, and they have Peter and the others arrested and thrown into prison. But just as the Holy Spirit has infused in them parrhesia—the boldness of speech that will not be cowed by threats—an angel of the Lord comes to open the prison doors. In a wonderful foreshadowing of Christ’s return in glory, Peter and the others are given a physical freedom that corresponds to their spiritual freedom. They walk out and speak the words of life. Brought back to the principal’s office once again for a reprimand, Peter explains his behavior: “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29).

Peter’s statement about obedience to God and not me epitomizes the Bible’s teaching about how to become free men and women, how to become capable of doing what we want to do rather than what we hate. The key to freedom is the power of our loves and loyalties, not the accumulation of rights or the removal of limits and constraints.

The Jewish tradition grasps this fundamental truth about freedom. Among the Hebrew words freedom are chofesh (found in Exodus) and dror (found in Leviticus and inscribed on the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia). It is not these, however, but rather the word herut which is the most significant for the Jews. This is an odd choice.

Herut appears in 1 Kings 21:8, where it is usually translated as “elders” or “ministers,” which is to say those dedicated to God’s service. Stranger still is the path by which this word comes to mean freedom. The ancient rabbis substituted herut for a harut in Exodus 32:16. (The absence of vowel marking in biblical Hebrew opens up the avenue for this substitution.) In that verse, harut means “engrave.” God has engraved the Ten Commandments in the stone tablets that Moses carries down from Mount Sinai. Thus, by the twists and turns of rabbinic reasoning, “engrave” really means “dedicate,” which really means “freedom.”

Unlike Christianity, Judaism often articulates core doctrines through striking and sometimes counter-intuitive interpretations of biblical verses or specific commandments. In this case, the ancient rabbis are defining freedom. To be free, we must engrave God’s commandments on our hearts. Of course, the rabbis were not inventing this notion. It is expressed in the prophetic promise of Jeremiah 31:33: “I will put my law within them, and I will engrave it on their hearts.”

The same view of freedom dominates the New Testament. Hebrews 8:10 quotes the verse from Jeremiah, and in many places St. Paul teaches that faithful obedience to Christ brings freedom. With the law of Christ engraved on our hearts, we are enabled to say ‘no’ to the worldly powers that seek dominion over our lives. Or to use Peter’s words, if we obey God, then we will have the wherewithal to refuse to obey men when they command otherwise.

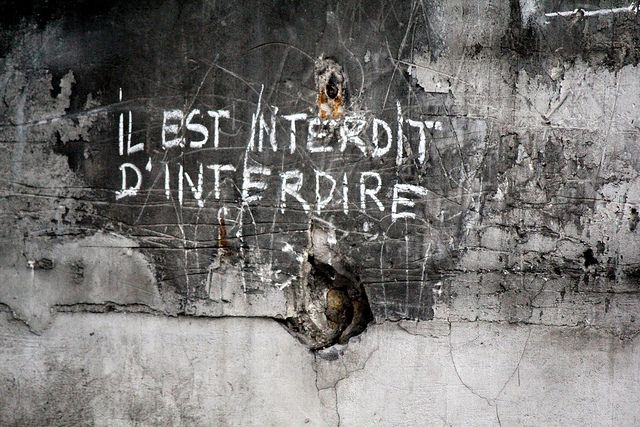

One need not adopt the Jewish or Christian faith to see the truth in this definition of freedom as herut. I have defined freedom as doing what we want to do rather than doing what others tell us to do. Of course, there will always be others telling us what to do. One of the pernicious aspects of today’s progressive cultural project is its utopian ambition to usher in a world in which nobody is told what to do. This utopian dream explains punitive political correctness. Its aim is to silence traditional judgments and condemnations. As the students in the streets of Paris in 1968 scrawled on walls, “It is forbidden to forbid.”

This approach, the approach that seeks to expand freedom by creating a paradoxically obligatory culture of non-judgmentalism, does not just fail in theory. As we can see today, it is failing in fact. That’s because it believes freedom to be something we can be given, when in truth it is something we must win through the labor of devotion. In St. Augustine’s formulation, my love is my weight. If I love something, I am drawn toward it, and I want to act in accord with my love rather than as others command me to act. Thus, the more powerful our loves, the greater the freedom we enjoy, for love galvanizes our souls. The power of love’s ‘yes’ allows us to say ‘no’ to anything that runs counter to that which we truly desire.

The key to the recovery of freedom is a restoration of strong loves. These loves need not be religious. The loyalty of a mother to her children can be fierce, as can patriotic loyalty and many other loves. A properly functioning university nurtures a love of truth, and this love is one reason such an education is called ‘liberal.’ It prepares a young person to stand upon what he knows to be true. Nevertheless, in my estimation it will fall upon those of us who are religious to play a leading role in the restoration of our culture of freedom, for religious faith has a supernatural strength that is stronger than any worldly power.

In a world in which so many feel in bondage—especially to the hearth gods of health, wealth, and pleasure—the freedom religious faith brings has a special allure. Some years ago, I was speaking with a young professor at a regional state university in California. He had been raised by his mother and her lesbian partner in an irreligious household. But as a college student he became an Evangelical Christian, and he became loyal to the bible’s teachings about sexual morality. In his role as a professor, his frankness and boldness of speech meant that his views on LGBT issues were well known and widely condemned by his colleagues and student organizations. Yet his classes were over-subscribed. “Why,” he asked me, “do they come to me? Almost all my students hold the conventional, progressive views about sex and sexual orientation.”

“They see the costs you’ve paid for your views,” I replied. “They recognize that you are free. They may not want to become conservative Christians, but they want that freedom for themselves.”

In a meditation on freedom, the man then known as Joseph Ratzinger made an interesting observation: “The free man is the person who is at home, who really belongs to the house. Freedom has to do with being at home.” Ratzinger went on to link home with inheritance. As St. Paul writes in Galatians 4, in Christ we are adopted as sons and daughters. Thus, “through God,” he tells the Galatians, “you are no longer a slave but a son, and, if a son, then an heir.” My fatherless young professor friend was at home in our Father’s house. He was an heir to the riches of the apostolic faith. He was free because he had a place to stand and resources to draw upon.

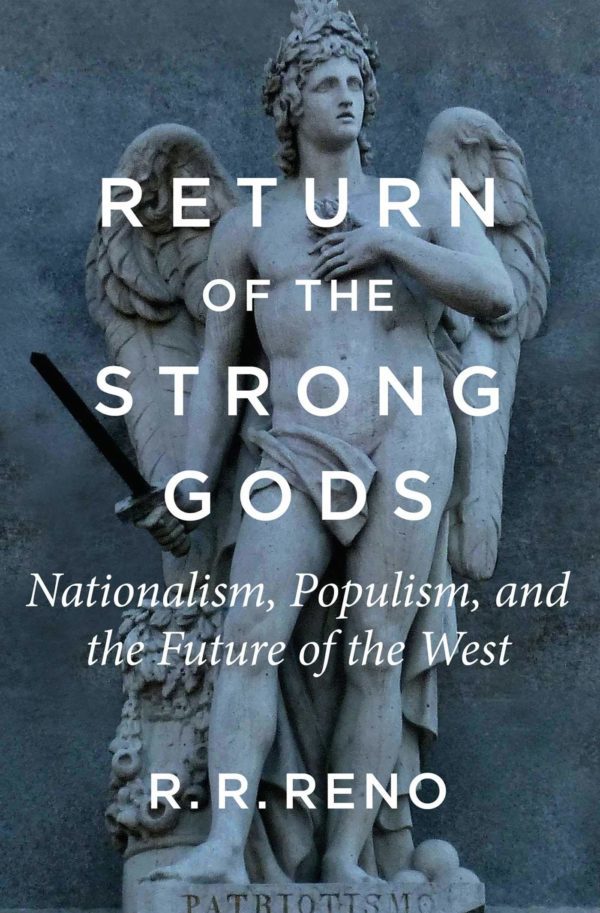

In my recent book, The Return of the Strong Gods, I use the metaphor of strong gods to evoke the cultural authorities and metaphysical realities that are home-making and inheritance-giving. Put in philosophical as opposed to theological terms, the free man does not need financial resources. Far more important is his need for an inheritance that evokes his love and guides his life. The free man needs a place to stand.

Put simply, the key to renewing freedom is exactly the opposite of what most progressives imagine. Social and religious conservatism provide homes and promise inheritances. Freedom—the boldness of speech and courage to live in accord with one’s deepest convictions—is among the most noble achievements of the West. If we’re to renew this promise of freedom, we must be patrons of the strong gods.