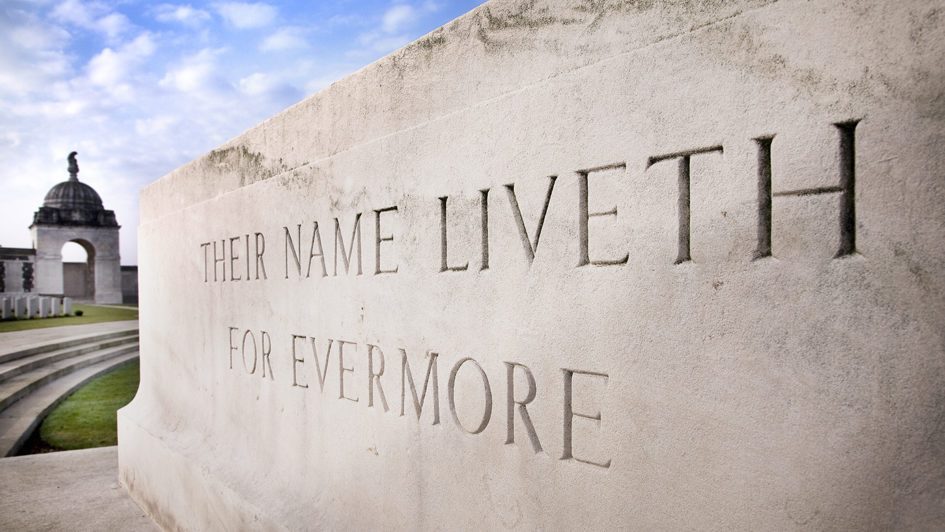

PHOTO: VISITFLANDERS VIA FLICKR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“Their Name Liveth for Evermore,” read stone inscriptions at cemeteries and memorial sites in the countryside around the Belgian town of Ypres. Once a bustling walled medieval commercial center whose textiles found their way across Europe and even to Russia, this small crossroads in Flanders became one of the bloodiest battlefields of the First World War. It was a major combat zone not just once, but five times. Three of the battles were massive enough to be ordered numerically, with the Third Battle of Ypres commonly called ‘Passchendaele,’ after the town that was its main objective.

The total number of casualties sustained by all combatant powers at Ypres reached a ghoulish 1.7 million, more than twice the losses at Verdun, a French fortress town where during much of 1916 the Germans sought to break through the unforgiving Western Front. Geography consigned Ypres to its fate. On three sides, the town is surrounded by ridges that slope gently up to commanding positions that the advancing Germans managed to capture in the early weeks of the war, though they failed to hold the town itself. Preventing them from seizing Ypres and its crossroads was a do-or-die mission. Yielding would allow the Germans to break through to the sea, frustrating any Allied ability to hold the front.

It was here, in late 1914, that the first serious trenches appeared as defensive positions, in what would become a theater of operations defined by trench warfare. In a matter of weeks, the earlier open-field battles had slaughtered some 80,000 men. So many of them were young soldiers that the dispirited Germans referred to their losses as the “Kindermord bei Ypern”—a ‘slaughter of innocents.’ Ypres was the first place where German forces used poison gas, initially chlorine, and later deadlier mustard gas. The Allies responded in kind. In October 1918, as the final offensive of the war pushed out the demoralized Germans, a British gas attack temporarily blinded a 29-year old Austrian corporal serving in the Bavarian Army. His name was Adolf Hitler, and he later claimed to have remained vision-impaired while he was lying in hospital, where he heard news of the humiliating armistice that ended the fighting.

Visiting Ypres today is a somber affair. The surrounding farmlands were the main battlefield, but the town itself was almost totally destroyed by German bombardment in the autumn of 1914. The devastation was so great that Winston Churchill, who returned to government after his disgrace at Gallipoli and served as Britain’s secretary for war, wanted to depopulate the town and transform its environs into a vast memorial site. He was overruled, but the legacy of what happened there is as inescapable as Gettysburg, Stalingrad, Dresden, or Hiroshima. Memorialization of the titanic struggle lies in every direction, enveloping modern Ypres’ approximately 35,000 inhabitants as they live lives infused with constant reminders of the carnage. The town’s well-appointed chocolate shops offer selections devoted to the war years, including confections done up in the shape of poppies, which Britain adopted as a mandatory lapel fixture for Remembrance Day. Over a century later, the custom still commemorates the armistice. Ypres’ entry gates were replaced with a vast arch bearing the names of more than 58,000 fallen.

A proper tour starts with the Tyne Cot military cemetery on Passchendaele Ridge, an elegant neoclassical array of gravestones and monuments laid out symmetrically. From June to October 1917, British and Imperial forces battled to dislodge the Germans from their position atop it, which was the center of their line. The British plan opened with a preliminary flank attack by mines. Centered around the hamlet of Messines, the assault dislocated part of the German line, killing 10,000 enemy troops in a matter of minutes. In July, an artillery barrage of some 4.25 million shells fired from 3,000 British guns tried to give the infantry their best chance in frontal assaults. The advance was expected to clear the ridge within 72 hours, but alas the Germans remained so well dug in that the operation took 103 brutal days. The worst rains in thirty years transformed the battlefield into a vast pit of mud.

By the time it was over, with British and Canadian troops finally reaching the crest, the momentum to press any advantage was lost even as the British commander, the infamous Douglas Haig, claimed victory. His small dent in the German line had cost 250,000 dead and wounded on each side, for a total of half a million. About one-third of the dead were never recovered, while another third could not be identified. Bones continue to turn up even today as farmers cultivate the ancient fields, which have seen yet another world war pass through in the meantime. Oblivious cows graze right up to cemetery walls as archeologists and forensic scientists use modern techniques to identify the fallen, who are then interred in cemeteries still open to receive casualties to be laid to rest.

Ypres’ Cloth Hall, once a vast trading emporium that was rebuilt after the war, boasts one of Europe’s finest museums, the In Flanders Fields Museum, so named for the famous verse of the Canadian war poet John McCrae, who served at Ypres as a lieutenant colonel in the medical corps. He survived, only to die of pneumonia in January 1918. The museum features a bottom-up view of the war, displaying battlefield artifacts, testimonials of soldiers, reconstructions of trenches and battlements, and other exhibits designed to make the experience of combat real and palpable. Among its highlights are illuminated panels featuring actors who portray combatants and read lines from their letters, journals, and memoirs. Preliminary panels instill the vital lesson that the war could only have happened because of overweening state power over the lives and perceptions of the peoples of Europe as they plunged into the abyss. A searchable computer database includes the names of all those who died in combat in Western armies over the course of the struggle.

When I visited last month, the museum offered a special exhibition on the First World War in the Middle East. Intriguingly laid out in the manner of Bedouin tents, it too included numerous personal artifacts, many of them privately owned, but was rather short on military strategy and the course of the war in that troubled part of the world. Three television monitors with academic experts belting out commentary was mercifully available only by optional handset audio device and could be avoided if one had already heard their stale shibboleths. The most important words, however, surely belong to McCrae:

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.