On Friday, October 24th, the Swedish Moderate Party, which heads the center-right government coalition, decided at its national convention that it is time to “research” a currency transition for Sweden.

Finance minister Elisabeth Svantesson, a leading member of the Moderate party, is firmly in favor of taking another look at euro membership. According to the daily newspaper Expressen, others within the party are even more open in their support for replacing the krona with the euro. Among them is Niklas Wykman, deputy finance minister with responsibility for financial markets. In his view, “a lot has happened” since the Swedish people voted to keep the krona in a referendum in 2003.

Superficially, these statements from leading members of the leading party in the governing coalition seem to be little more than normal political chatter. However, Swedish politics characteristically does not generate big waves when big changes are coming.

If anything, it almost works the other way around. The country’s political leadership expertly brings about big changes in small steps, each one of which is small enough not to attract the attention it really deserves. This odd practice, while blatantly opposed to the political ethos of a democracy, has allowed for major societal overhauls and upheavals at a level that would be impossible or stir public unrest in other countries.

This method was used, e.g., in swaying the Swedes from opposition to the EU—or the European Communities, as it was called at the time—to a firm approval of said membership in a referendum.

The 2003 referendum on the euro could be seen as an aberration, a misstep, by the Swedish political elite. The outcome ‘should’ have been positive for the euro, but with 56% opposed and only 42% in support, there was no practical way around public opinion at the time.

Since then, Swedish euro membership has been a largely dormant political issue, though it has popped up from time to time. Leading pro-euro politicians have tested the waters of public opinion, but to date, the question asked at the 2003 referendum has not been officially reintroduced into the public discourse.

Until now, that is. With the Moderate party—the third largest in the 2022 election and political home to Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson—vowing to officially “research” euro membership, we can safely conclude that they are going to go into the 2026 election with a pro-euro profile.

This means in practice that the prime minister who takes office after next year’s election will lead Sweden into the euro zone. Whether this prime minister will be Kristersson in a new center-right coalition or Magdalena Andersson, the leader of the Social Democrats, the euro issue will be inextricably tied to the serious economic problems that Sweden is currently wrestling with. Their GDP is currently growing at a paltry 1.4% per year, while unemployment is at a troubling 8.7%.

I can easily foresee how the euro membership will be sold to the general public as a magic wand that will fix the country’s economic woes. In reality, it will bring more problems to the Swedish economy than it could ever be purported to solve. These problems fall into two categories, which I touched on in two articles in 2023: Sweden is economically heavily dependent on its exports, and the country is not prepared to hand over its fiscal policy to the EU and its debt-and-deficit rules.

The heavy dependency on exports for GDP growth is not unique to Sweden. However, due to excessive taxation, the domestic economy makes relatively scant contributions to the growth and evolution of the Swedish economy. As a result, Sweden is also more dependent on keeping its own currency than other EU states that have chosen to stay out of the euro.

To see what price Sweden could pay for ditching the krona, let us do a little experiment based on the assumption that Sweden had joined the euro in 2000. Theoretically, this is akin to Sweden adopting a fixed exchange rate between the krona and the euro; for economic decision makers, it really does not matter if two countries have a fixed exchange rate between them or share the same currency. (In reality, of course, the difference is that when they share the same currency, the actual money in both countries is the same.)

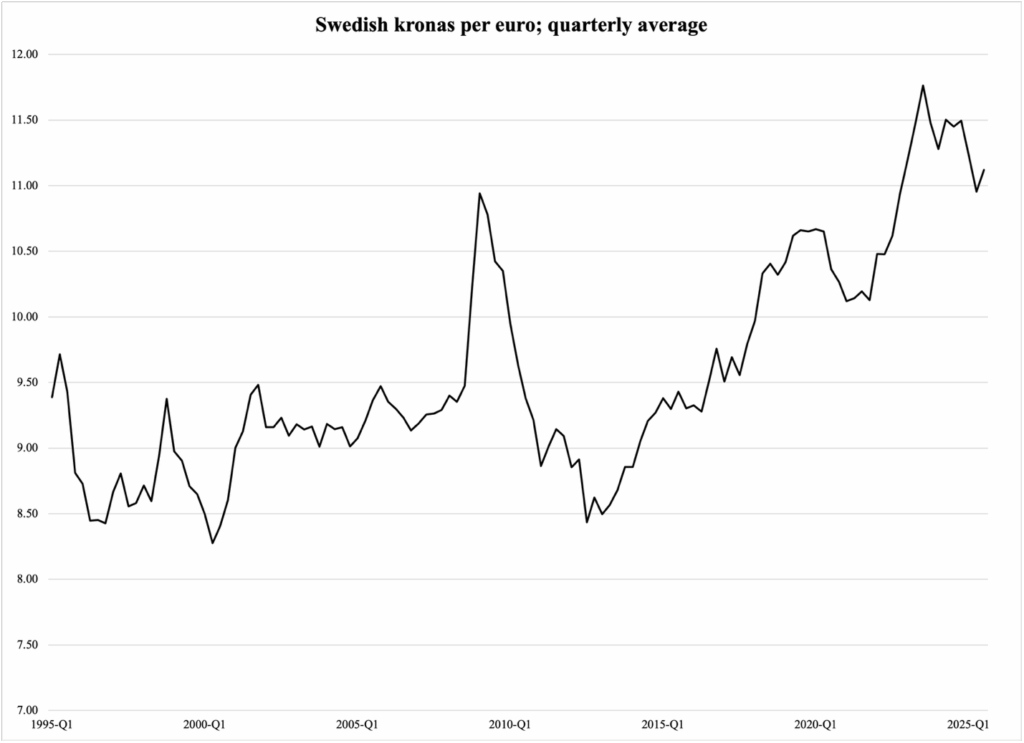

Figure 1 reports the exchange rate between the Swedish krona and the euro—and its predecessor, the non-minted ECU—over the past 30 years. The Swedish central bank has allowed the krona to float against the euro, which has led to a gradual weakening of the Swedish currency. This is an essential point that we will bring with us into our experiment:

Figure 1

In 2000, the annual average exchange rate was 8.44 krona per euro. If January 2000 had been the beginning of Swedish euro membership, the country’s Swedish exporters would have planned their production and their sales efforts within the currency area de facto with that exchange rate in mind.

In reality, as Figure 1 shows us, from 2000 on, the krona has weakened vs. the euro, which means that exports from Sweden to the euro zone become cheaper relative to the cost of production. This means that Swedish exporters have gradually made more money exporting to the euro zone without having to do anything to improve profitability at home:

This is a 29.8% rise in sales revenue exclusively from the weakening of the Swedish krona.

Conversely, this exporter could have lowered the price of the product in terms of euros from €113,500 in 1999 to €87,400 in 2024, and the company would still have covered its production costs. (Again, we disregard inflation.)

Suppose, now, that the euro is introduced in 2000. From that day on, there is obviously no profit to be earned from the weakening Swedish krona. There is also no opportunity for the company to cut their product prices—unless they first alter their production methods.

This last point is crucial. Over the past quarter century, Swedish exporters have been able to make good money in euro-denominated markets without making the same investments as competitors in the euro zone have made. The gradual weakening of the krona has created an artificial advantage that continues to benefit Swedish companies today.

Due to their long experience with a profit boost from a weaker currency, I very much doubt that Swedish exporters will be able to transition into a situation where they operate within the euro zone.

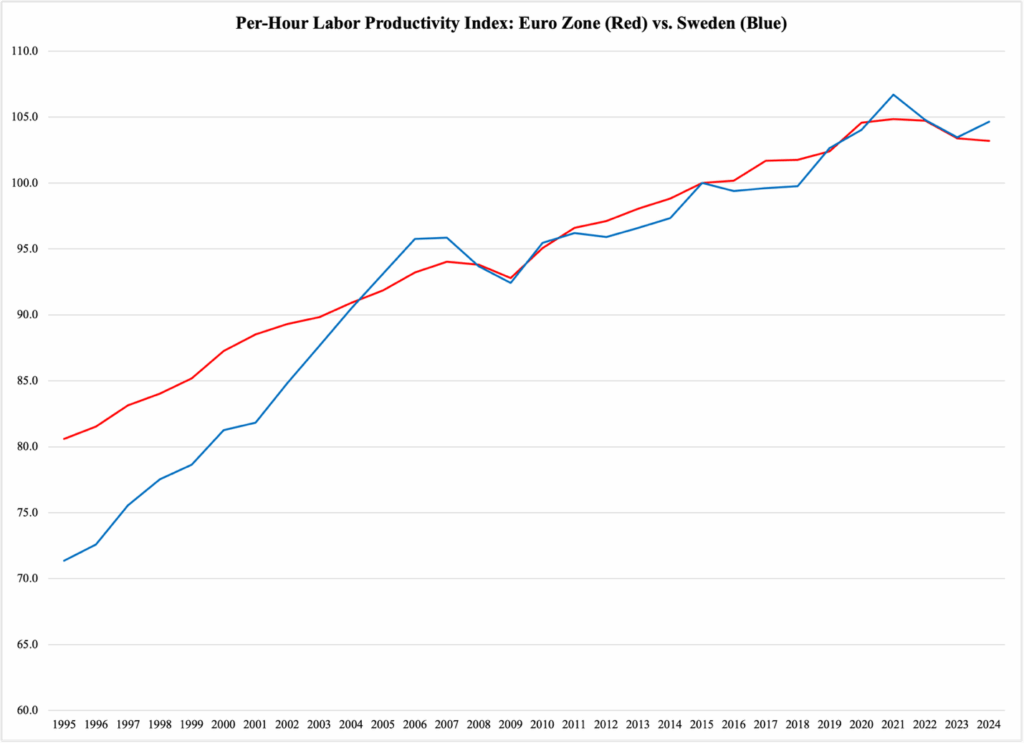

One reason for my doubts has to do with labor productivity. Figure 2a reports the evolution of per-hour labor productivity in the euro zone and in Sweden. After initially seeing a faster increase in labor productivity, Sweden falls in line with the euro zone from circa 2005:

Figure 2a

The compelling message in Figure 2 is that the Swedish workforce has improved its productivity on par with the euro zone—which, we can safely assume, also means that the country’s exporters to the euro zone have improved their labor productivity along the same trajectory.

With a workforce that is no less productive than that of the euro zone members, Swedish exporters earn extra profits from the gradual weakening of the krona. But what happens if we remove that source of extra profits? How are Swedish businesses going to stay as profitable as they have been over the past 20 years?

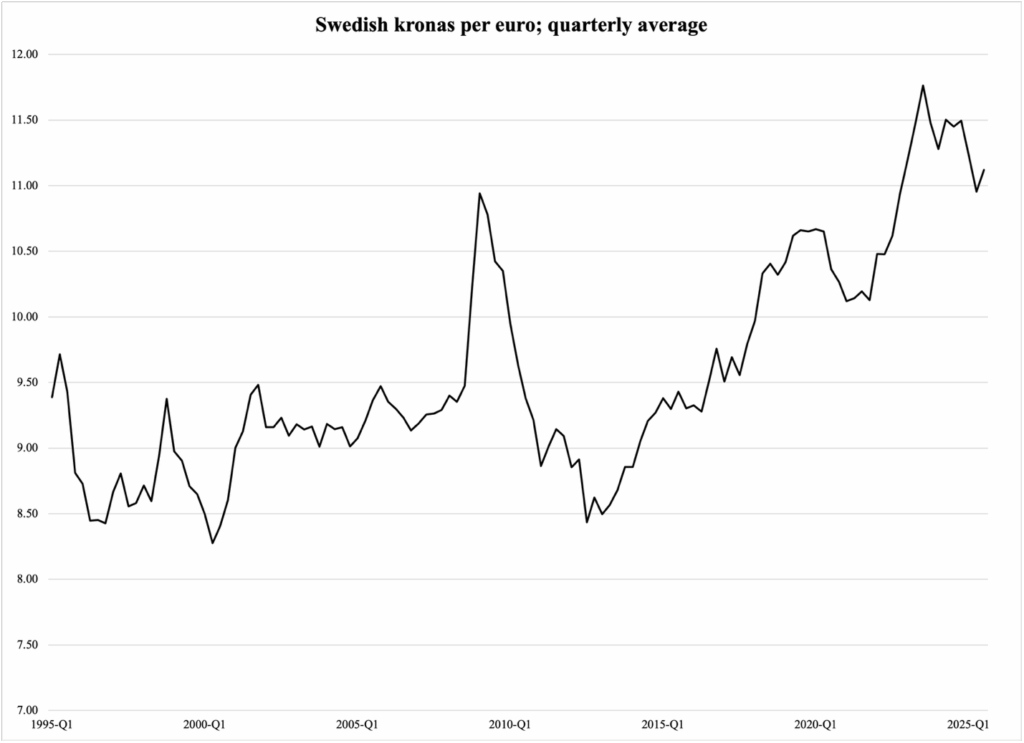

Can they improve labor productivity enough to compensate for the loss of the currency advantage? Figure 2b shows the trajectory that Swedish labor productivity would have had to take to compensate for the exchange-rate-based profit opportunities:

Figure 2b

There is absolutely no way that the Swedish labor force could have advanced its productivity along the dashed line. In fairness, though, labor productivity is not the only factor affecting corporate profitability. Other countries have entered the euro zone, with varying results. The problem for Sweden is that the entry would come at a time when the economy is weak and showing no signs of improving. Removing the exchange-rate-based advantage for the export industry may prove to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.