American news media have been filled recently with predictions of a so-called stock-market correction. This is insider speak for a sharp, rapid decline in stock values.

On July 28th, SeekingAlpha, a financial-news specialist, bluntly said “you know the correction is coming, right?” Bloomberg went a step further, predicting a 15% decline “as sky-high equity valuations slam into souring US economic data.” On July 23rd, The Capitalist shared three warning signs of a market correction; four days later The Wall Street Journal upped the ante with five warning signs.

European news media have not been as dramatic regarding financial market outlooks; worries about a stock market correction seem to be mostly absent. There is one prescient exception in the form of Stephen Edelsten, an asset fund manager who expressed his concerns in The Financial Times on August 1st. Pointing to the British stock-market index FTSE and the U.S. S&P 500 as being over-inflated, Edelsten added:

In Europe the Euro Stoxx 50 recently broke a record that had stood for 24 years, which tells you something about the state of markets there over the past couple of decades.

This could be interpreted as a verdict on how virtually lifeless European stock markets have been. However, it also sounds like a warning of the same kind that U.S. media have been dispensing recently.

Should we take all these warnings seriously? Yes, we should, but we should not panic over them. The conditions for a stock-market correction in America are different from the same conditions in Europe, in no small part because Europe still does not have a continent-wide stock market. The individual countries maintain their own markets, with all the associated costs and benefits of that.

One benefit is that any drastic downward correction in America does not automatically spread all across Europe. There are important differences between European stock markets, differences that help us assess whether or not there is any risk for a major correction—again, meaning decline—in any one of those markets. For the sake of brevity I will illustrate this point by looking at four examples: the stock markets in France, Germany, Hungary, and Sweden.

When it comes to stock-market analysis, there are many ways to analyze risk, and many forms of risk to analyze. They mostly concentrate on risk related to individual stocks; the question here is how we can illustrate the presence, or absence, of risk that the whole market is going to ‘correct’ itself.

To do that, we need compelling but relatively simple data. The choice of that data is motivated by the core purpose behind a stock market—in short, why we have stock markets in the first place. The equity traded on a stock market is a certificate of ownership—a property right. Each share in a corporation is therefore a certificate of ownership, even if it is only a fraction, of a specified corporation.

When we trade stocks at the stock market, we get real-time updates on the value of a publicly traded corporation. That evaluation ultimately depends on corporate profitability—which, in turn, depends on the purchasing power and growth of individual markets and industries.

If we look at a properly working stock market in its entirety, it is, in effect, an evaluation tool for the national economy. Since we measure the national economy as GDP, gross domestic product, we can therefore compare an index representing the value of the stock market with the nation’s GDP:

Any value in the stock market that exceeds what is motivated by GDP is by definition speculative value.

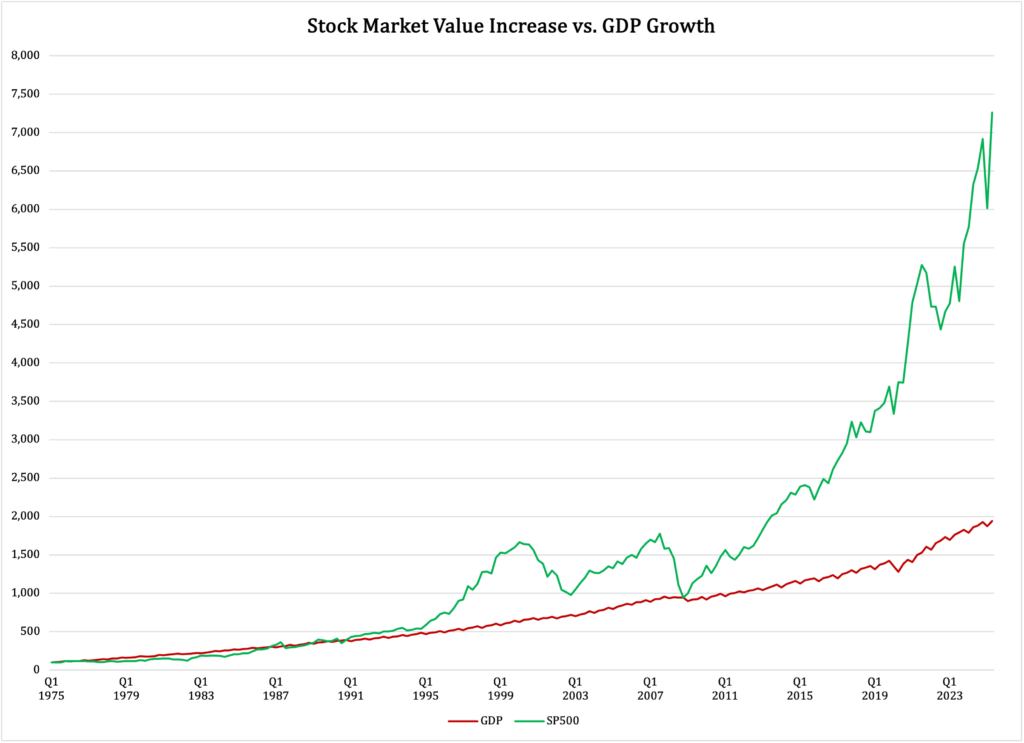

To illustrate how we can compare stock-market value to GDP, we use the U.S. stock market as illustrated in Figure 1. It reports the growth of the market index (green) and of GDP (red) since 1975. To identify the extent to which the two variables are growing in alignment, we assume that they both start out at a value of 100. We then grow each variable as it has grown over the past 50 years.

For the first 20 years, the U.S. stock market grows on par with the nation’s GDP, suggesting that the value of America’s largest corporations is determined by economic substance. However, more recently, the stock market has broken loose from GDP and is now living a life of its own:

Figure 1

As mentioned earlier, the portion of the total stock market value that exceeds the total value of the U.S. GDP is by definition speculative value. As Stephen Edelsten notes in his aforementioned article in Financial Times, the speculative portion of the stock market’s value depends on the expectations that the investors have. If those expectations collapse, i.e., if investors no longer believe stock-market speculation to be profitable, then, at least in theory, the correction of the stock market’s value would eradicate the difference between the expectations-inflated value and that of GDP substance.

In practice, in a market with such a major speculative share in total stock market value as we have here, any downward correction will only eliminate a minor part of the speculative value. It would take a complete economic calamity to eradicate the speculative value that currently sits atop substance-based stock values.

Turning to Europe, we will look at the stock markets in Sweden, Germany, France, and Hungary. The selection is based partly on available data from investing.com (stock market) and from the United Nations national-accounts database (GDP). It has not been possible to create the exact same time series for every country, but these four offer long-enough perspectives to make their presence here meaningful.

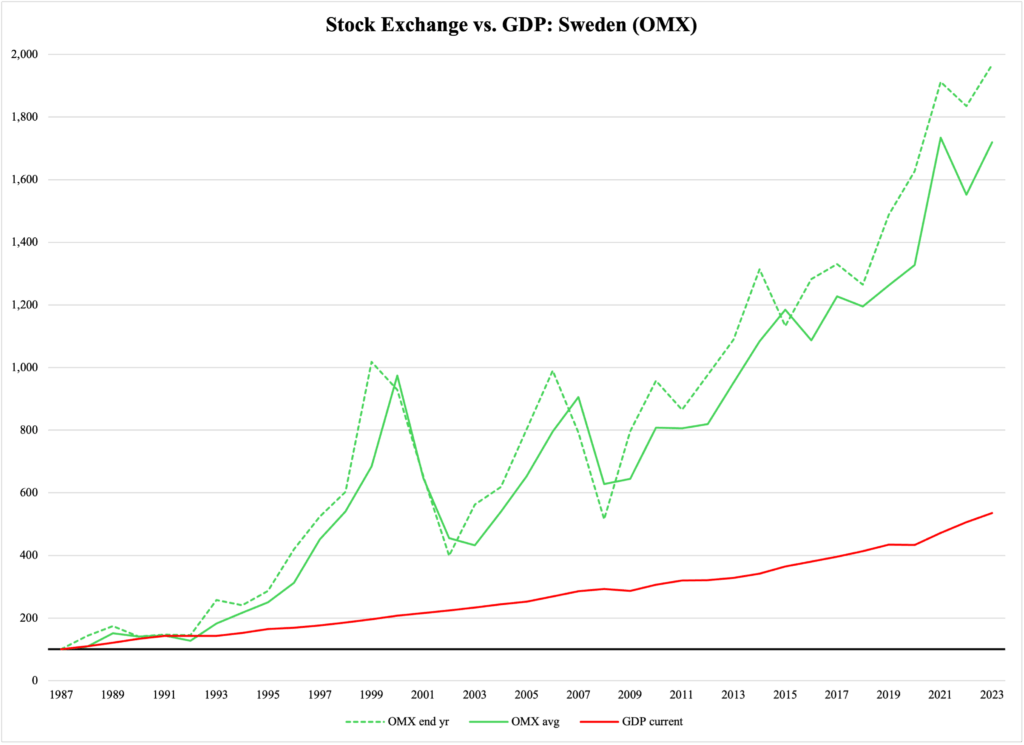

Partly, the selection is motivated by the fact that these four countries represent very different economies within the same European Union. Let us start with Sweden where, as Figure 2 shows, the stock market has gone into a speculative haze in much the same way its American equivalent has.

Figure 2

To be blunt, the Swedes should expect a significant spillover if there is a ‘correction’ on the stock market in New York.

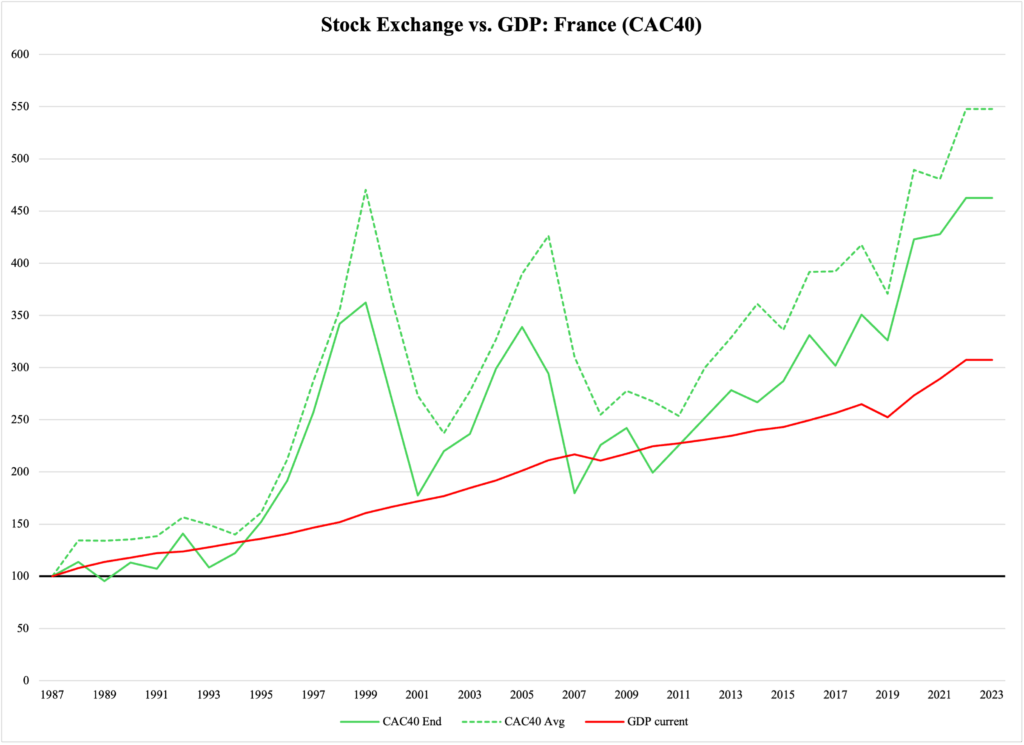

The stock market in Paris is also to some degree exposed to speculation, but not nearly to the same extent as in Sweden. As Figure 3 shows, the market index has grown faster than GDP for the most part but until recently, there have been no troubling trend in the market. That has changed in the past ten years, when the CAC 40 has outpaced the French economy:

Figure 3

If a course correction happens in the American market, the spillover to France should be limited, in part because the speculative balloon in French stock values is not dramatically large.

Over now to Germany—and a weird stock market. Behold Figure 4:

Figure 4

The stock market lags behind the German economy! This is a fascinating situation that requires an equally fascinating explanation, but before we get there, it is worth mentioning that because the stock market has underperformed compared to GDP, there is no risk for a speculative bubble to burst at the German stock exchange.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, there is only one reasonable explanation as to why a country’s GDP would grow faster than the value of the corporations that constitute its private sector. The German economy is highly dependent on exports, while the stock market would be dominated by domestically oriented businesses. Since the domestic economy in Germany is faring worse than the exporting sector, and since the money earned by exporting companies do not necessarily benefit the domestic economy, the explanation here could be that the DAX stock-market index inadequately represents the role of the exporters in the economy as a whole.

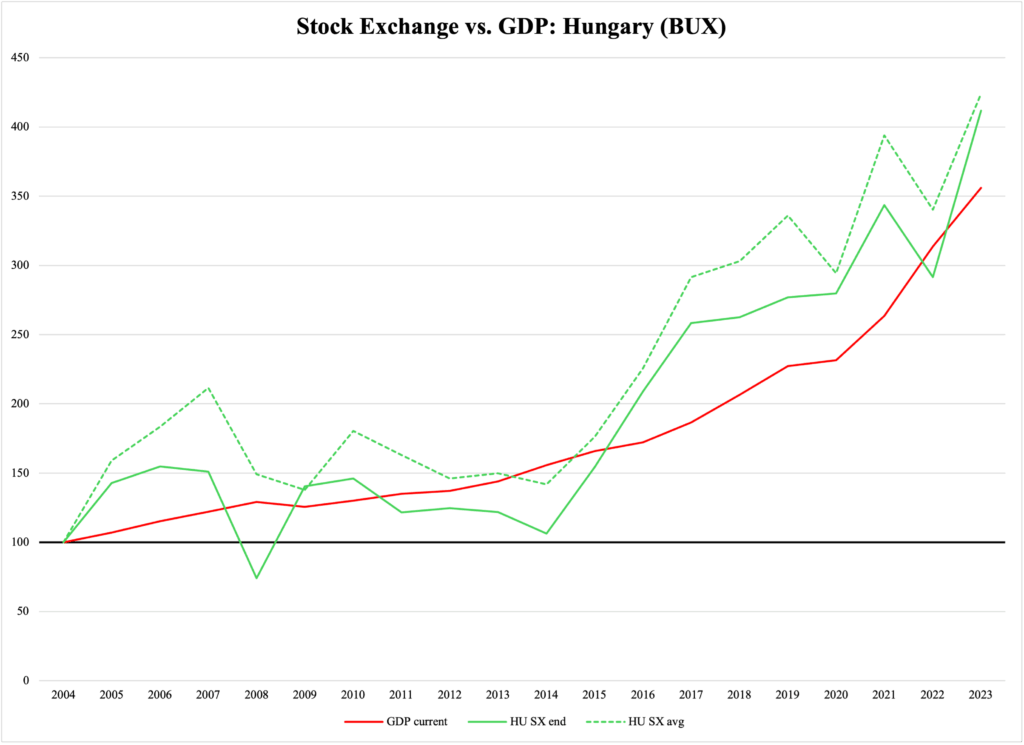

Last but not least, we take a look at Hungary. Among this sample of five markets (including the American), the stock market in Budapest exhibits the soundest balance between, on the one hand, growth and profits for shareholders and, on the other hand, the growth of the nation’s economy.

Figure 5

Hungarian corporations are well in tune with what their nation’s economy can produce and its growth over time. By the same token, the political leadership of the country has conducted a thoughtfully business-friendly economic policy, where productive growth has been so strong that it has kept speculative capital largely out of the stock market.

One plausible explanation is that the economy has generated so many opportunities for productive investments, as opposed to its speculative counterpart, that there has been ‘no time’ for the build-up of a speculative bubble.

All in all, this short review of select stock markets tells us that if Europe were to suffer contagion from a U.S. market correction, it would hit countries like Sweden, and to some degree France, harder than others. We also learned that there are two paths to a speculations-proof stock market: the German path, where the economy performs so poorly that the stock market actually lags behind GDP; or the Hungarian version, where strong GDP growth opens for strong stock-market investor returns without detrimental effects in the form of financial instability.