Germany has once again suspended its debt brake. This is big news—bigger than the media has realized. It is a symptom of two systemic economic problems in the European economy:

The second point is directly connected to the German fiscal crisis. Let us return to it in a coming article. For now, we need to look more closely at the German situation, and how it is entirely a problem of their own making.

I wrote back in May about the ties between a perennially weak European economy and eroding government finances:

A stagnant economy typically triggers more payouts from welfare state benefit systems, while tax revenue falls behind government spending. Stagnation is the pathway to a structural budget deficit.

On November 9th, I reminded our readers of the unending deficits across the EU during the 2010s. These persistent deficits were seemingly immune to the business cycle, meaning that they remained even as Europe’s economies reached the peak of the business cycle. This is what economists usually refer to as a structural budget deficit.

I also pointed to fiscal data showing that Europe is having even more trouble reducing its deficits now than it had back in the last decade. This suggests that the structural deficit has been reinforced since before the 2020 pandemic.

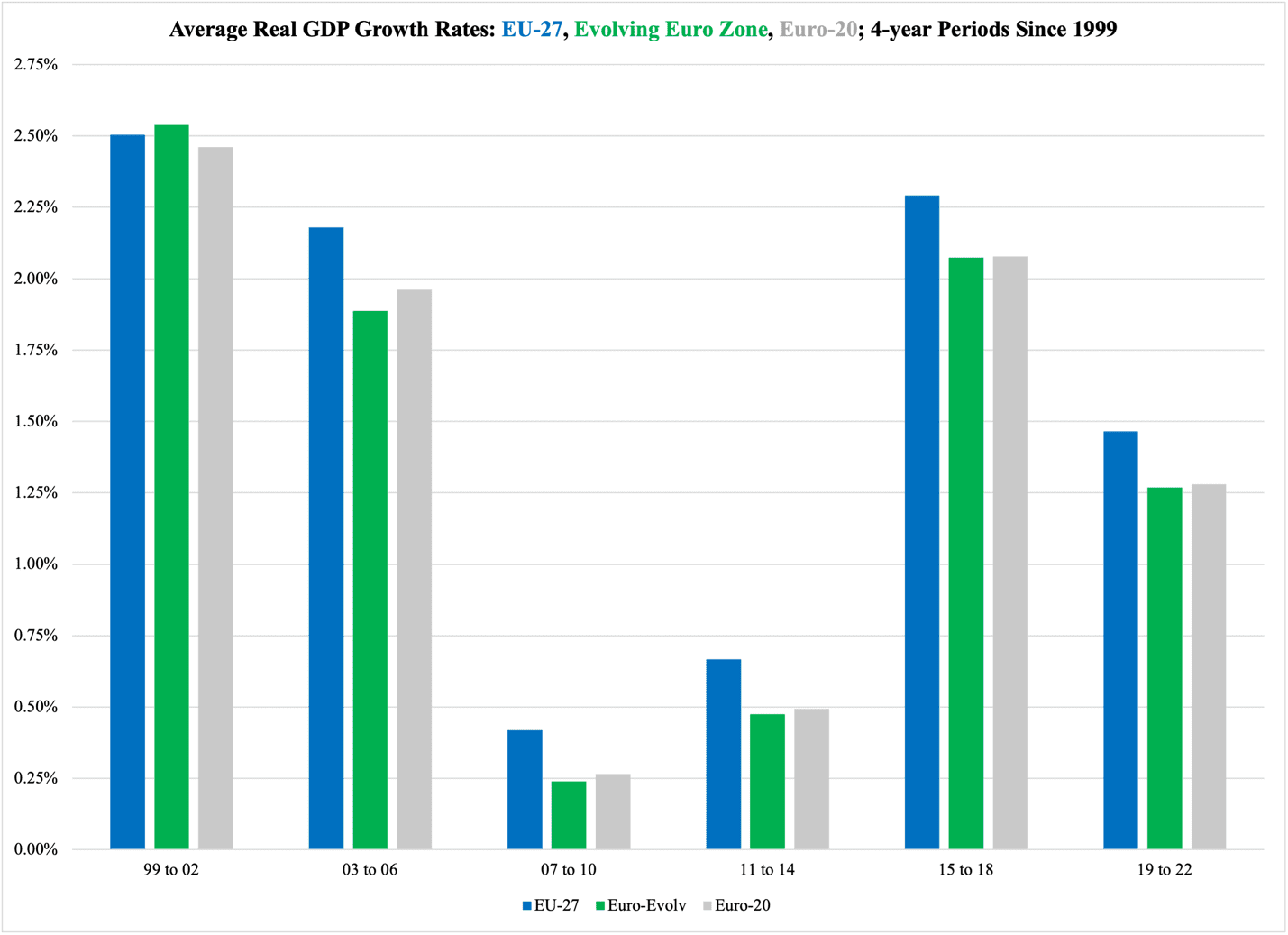

The recent pandemic did more damage than that: it aggravated the problem of economic stagnation. From 2019 through 2022, the economy of the 27-member-state EU grew by less than 1.5% per year. This number evens out the sharp drop in activity due to

As Figure 1 reports, the 2019-2022 period was worse than the preceding four years, 2015-2018. At the same time, it was also better than the eight years 2007-2014 (measuring the EU as its current 27-member configuration). This tells us that there is no particular trend in GDP growth for the EU, except that it is unlikely to return to 2% or more, at least in the near future.

Notably, the euro zone itself did worse than the EU as a whole. It does not matter whether it is measured as its current 20 members (gray columns in Figure 1) or as an evolving group of countries (green)—over the past 20 years the euro zone has trailed the EU-27 group by a constant margin:

Figure 1

As an economist who has been critical of the euro ever since the Maastricht Treaty was signed three decades ago, I am tempted to gloat over the fact that the euro zone is consistently performing worse than its non-euro zone neighbors. This is clear evidence that the currency union has become a shackle around the ankle of the economies of the member states. It has not delivered in terms of growth and prosperity as its proponents of yesteryear purported it would.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that even if the currency union ended tomorrow, Europe would not be the home of a sudden GDP growth spurt. The currency union does not bear all the burden of guilt for its sluggish economy. To take two examples, France and Germany, the largest euro zone economies, are perfectly capable of bringing their economies to a halt without having to share a currency. From the first quarter of 2020 through the third quarter of 2023, the French economy grew a total of 6.2% in real terms. Of the 14 EU member states that, to date, have reported GDP numbers for the third quarter, the French number is the third from the bottom.

Worst off is Sweden, with an economy that—adjusted for inflation—is currently 0.7% smaller than it was in the first quarter of 2020. (Are you all sleeping in Stockholm?) Second from the bottom is Germany, with a GDP currently 2.8% larger than in Q1 of 2020. Not only is this worse than France, but it is far behind e.g., Bulgaria, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Even the Netherlands has done better than Germany.

It is worth noting that these are not seasonally adjusted numbers, which can tilt the comparison a little bit. At the same time, the point has merit and can stand on its own two feet: if an economy has not grown more than marginally in the past 15 quarters, there is something profoundly wrong with it.

Just to get this point out of the way: the pandemic is not to be blamed, even though it involved an artificial economic shutdown. The resources that were left idling during the pandemic were all there to return to when governments eased their restrictions.

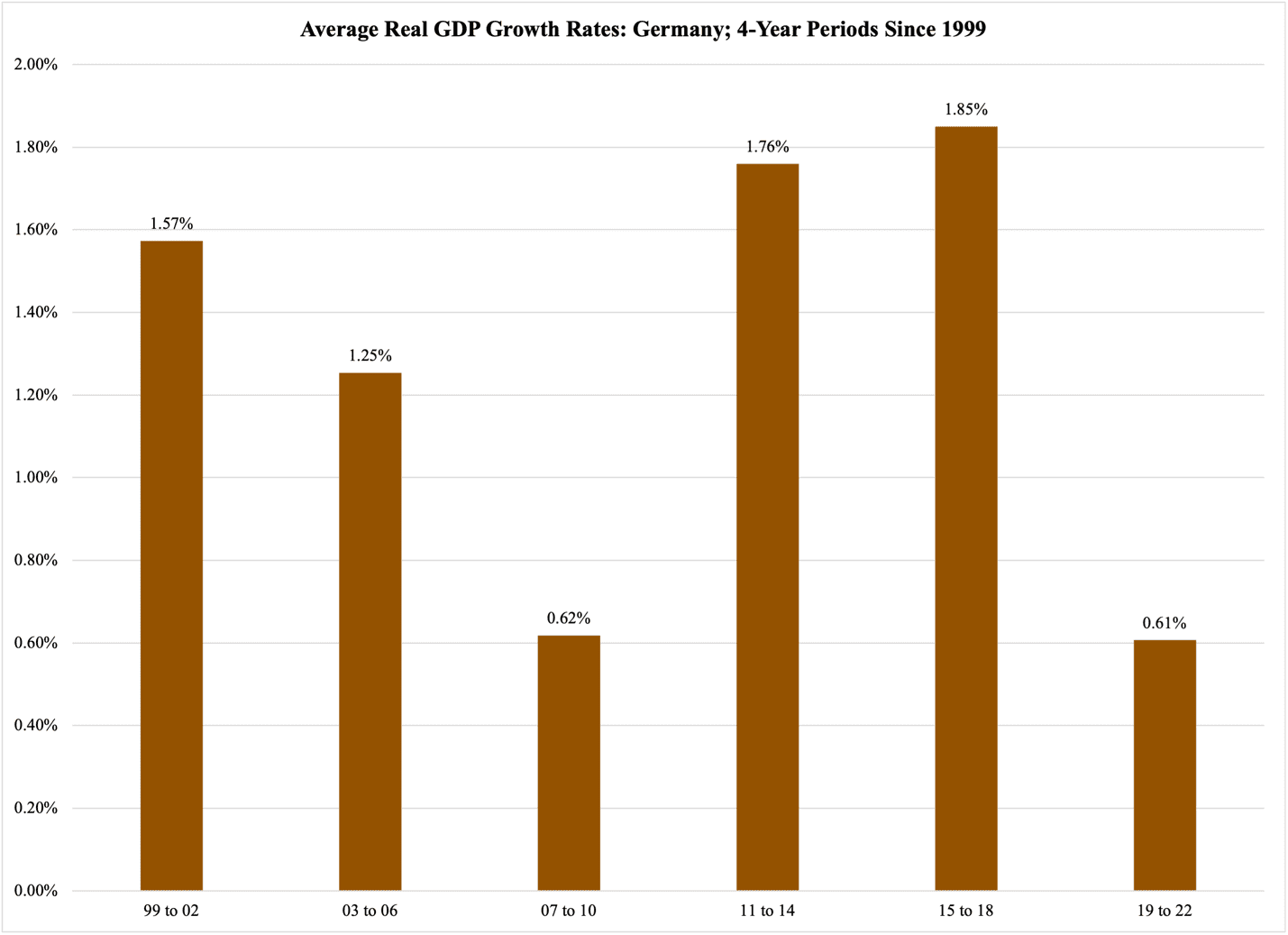

If anything, the pandemic highlighted underlying structural problems in some of Europe’s economies. Germany is a case in point: as Figure 2 reports, its GDP has not averaged 2% growth per year in any four-year period since 1999 (which marked the end of the ‘old’, pre-euro Europe). The 2007-2010 period was dominated by a recession so that, on average, German GDP grew at almost exactly the same rate as it did in 2019-2022:

Figure 2

So far through 2023, German GDP has ‘grown’ with the following numbers:

We now have two consecutive quarters with negative growth, which by definition puts Germany in a recession.

It is with this trend in mind that the German government has decided to suspend its constitutional debt-limit mechanism. This decision, which came against the backdrop of enduring criticism of the so-called debt brake, is not a good verdict on the ability of the German government to keep its fiscal house in good order. The reason is found in the very debt brake that has been blamed for the current budget chaos in Berlin.

This blame is unfair. The debt brake is not at all the fiscal straitjacket it has been portrayed as. It comes with two tiers of borrowing, one ‘structural’ and one ‘cyclical.’ This division between two credit lines, so to speak, allows the government in Berlin significant fiscal leeway in times of economic recession. While the structural cap on borrowing is 0.35% of GDP, the cyclical cap, which applies in times of recession, allows for debts up to 1.5% of GDP.

Since the German economy now has fallen into a recession, it would make sense that Chancellor Olaf Scholz would avail himself of this generous credit line. Based on 2022 figures, it would grant him the right to borrow more than €46.1 billion, or roughly three-quarters of the borrowing that Chancellor Scholz was trying to pay for with the unconstitutional transfer of COVID-related EU funds.

Under the debt brake, the Scholtz government would have been able to deliver everything they wanted in terms of government spending, except for €15 billion. This amount equals less than 0.8% of total expected government outlays in Germany in 2023. This is the amount of money over which Olaf Scholz and his government decided to suspend the debt brake.

As mentioned, this was the second of its kind in as many years. It is not a sign of fiscal strength, let alone economic leadership, when Berlin takes this lax attitude to its own constitutionally enshrined ambitions of fiscal conservatism. The frivolity toward their own rules should put the Scholz government under new scrutiny, but it also precipitates credibility problems for the euro zone’s ability to deal with the next fiscal crisis within its domains.

The worst part of the debt brake suspension is the fact that the German government appears to have no ambition to correct the underlying structural problem in their country’s economy—the very problem that has led to the fiscal situation they are now caught in. This structural problem is tied to the debt brake, but unlike what critics of the brake tend to suggest, this is not about the cap on public sector borrowing. Those critics call for government borrowing at large numbers in order to fiscally stimulate the economy out of a recession.

Conventionally, this argument is attributed to British economist John Maynard Keynes; in reality—if one bothers to actually study Keynes’s respectable scholarship—the imperative of Keynesian economics is to use government debt against economic depressions. Without going into the details of what separates the two, a recession is not a depression and therefore not subject to the same macroeconomic analysis. If managed properly, with limited spending, regulatory restraint, and low taxes, a government will have no reason to rely on debt to make it through a recession.

The German debt brake aligns with Keynes’s actual macroeconomic theory. Its authors probably did not read Keynes, but their product follows his recommendations. With the aforementioned 1.5% limit, it allows for enough borrowing to get a well-managed government through a recession; with the permission to suspend it entirely in the event of disasters, the debt brake is designed for both regular recessions—when its deficit ceiling applies—and for irregular conditions, or what in Keynesian terminology would be a depression.

Unfortunately, today’s German political leadership has forgotten the essential distinction between regularly occurring recessions and economic disasters or depressions. What is worse, they have ignored the structural shift that happened in the German economy when the debt brake was introduced.

With the risk of being overly repetitive, the debt brake only works if government is well-managed. A key ingredient of that management is that the government budget is balanced first and foremost through limits on spending. The bigger government spending gets as a share of GDP, the more difficult it will be for government to fund it on a regular basis: the bigger government grows, the more it weighs down on the economy as a whole. Hence, the growth in tax revenue slows down and falls behind the growth in spending.

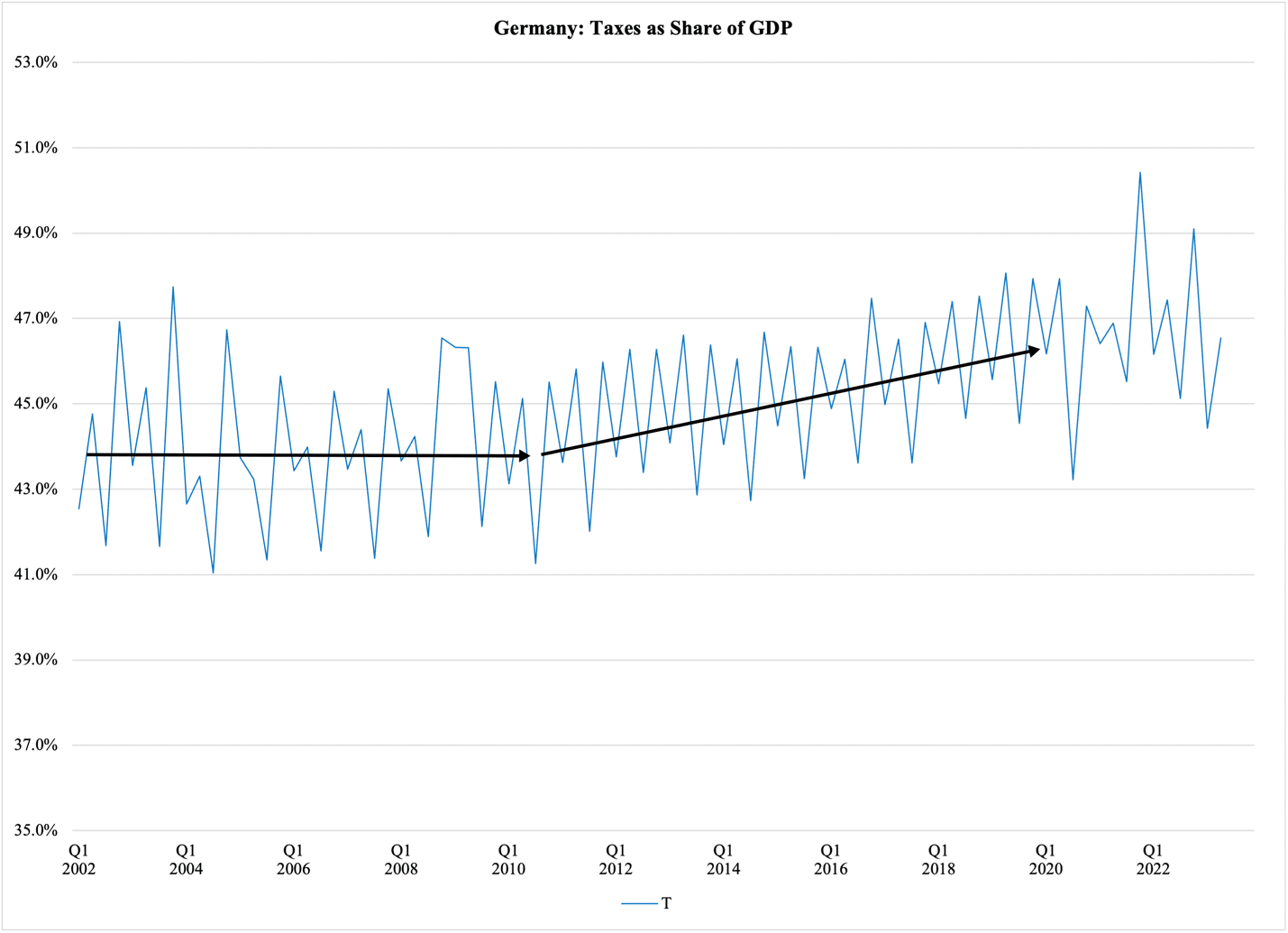

With slower growth in GDP comes slower growth in personal income. When a government continues to pursue balanced budgets without structurally reducing spending, it can only avoid deficits by raising taxes. As I explained in my 2021 evaluation of Angela Merkel’s time as Chancellor, the introduction of the debt brake in 2009 led to a permanent rise in taxes on the German economy. Figure 3 reports this increase by distinguishing between total taxes as a share of GDP before the debt brake, and after. The pre-brake period is characterized by an essentially flat tax-to-GDP rate; in the post-brake period, the tax burden slowly rises:

Figure 3

In other words, over the past 14 years, German governments have been chronically unable to keep their spending within the limits that an unchanged tax-to-GDP ratio would require.

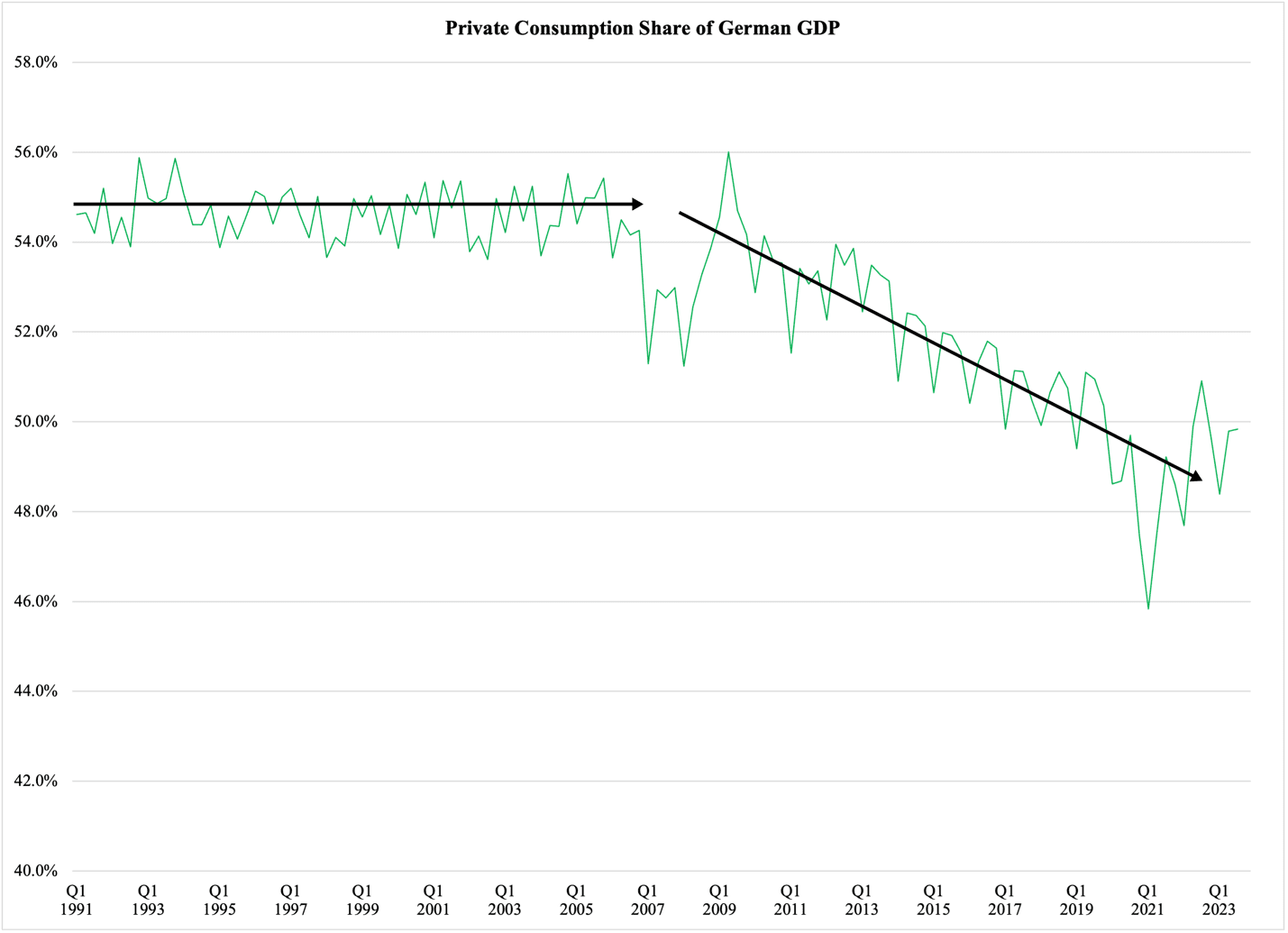

By raising taxes, the politicians in Berlin have secured an even lower growth trajectory for the German economy than it was already on. Another major consequence is that the growth that is still generated increasingly comes from other sources than domestic economic activity. The clearest sign of this is that private consumption is gradually becoming a less important end use of goods and services:

Figure 4

When the private domestic sector becomes less important, the demand for German output—both goods and services—must increasingly come from either of two sources: government or exports. With weaker government finances, foreign trade becomes the lifeline of the German economy.

So far, the German economy has always been saved by its formidable export machine. As we will see in a coming episode on the euro zone itself, Germany can no longer take this machine for granted.