One of the most frustrating aspects of everyday life for the younger generations, primarily the so-called Gen Zers—or Zoomers—of this world, is that they never feel they can get ahead economically. It almost does not matter if they go to college, learn a trade, or start a small business—they express a prevailing feeling of always working against the odds.

It is easy for older generations to roll their eyes at these lamentations from the young; after all, we did not exactly dance on roses throughout youth, did we? If you grew up during the Cold War, you learned to live with a low-level stress, knowing that we were never more than one 30-minute ICBM flight from an atomic bomb starting World War III.

With that said, though, the Gen Zers do have a point. It is definitely harder for those 30 or younger to establish themselves in today’s European economy than it was for their parents. For those of us who were born in the early years of Generation X, the economy was a lot more open and inviting than it is today.

I am not talking about formal laws or regulations. Young workers are not discriminated against; if anything, European legislation today is more favorable to every person who is trying to find a job.

As I explain below, this gradual erosion of economic opportunities is not a new phenomenon. Anyone with an open mind could see it coming 20-25 years ago. Generation Z is quite possibly the first who will be doomed to a lifelong struggle at the bottom of a stagnant economy. The daily struggle will be not to get ahead financially but simply to defend a standard of living with the very basics of what an industrialized economy can offer.

Their hopes to achieve their parents’ levels of prosperity are vanishing out the window, carried away by such depressing economic outlooks as the European Commission’s Autumn 2025 Economic Forecast. It predicts that the economy of the European Union will grow by an average of 1.3% per year, after inflation, through 2027.

This is well below what an economy needs in order to allow its young workers to achieve the same standard of living as their parents had. That threshold is at 2% real GDP growth per year.

The Commission’s Autumn 2025 outlook is frustrating, of course, but it is nowhere near as frustrating as the fact that economists like me have been pointing to Europe’s economic stagnation for years now, trying our best to draw the attention of the continent’s political leadership to the problem. I wrote a book about it more than ten years ago, Industrial Poverty (Gower 2014), where I explained the exact mechanics that cause this stagnation—and what it takes to break out of it. In Chapter 3, I define the concept of industrial poverty and how it depresses the standard of living.

Again, this is not a new problem. Not by a long shot. To those of us who saw this problem decades ago, it comes as absolutely no surprise. We are frustrated to see, just as we expected, that the young generation’s path to prosperity is longer and narrower than it was for us.

On top of all this, Europe’s young now face the structural uncertainty of what they will actually get in return for the high taxes they pay. Back in the 1980s, even into the 1990s, Europe’s welfare states reliably provided cash and in-kind benefits to those who were entitled to them. Today, there is an emerging debate in Germany, France, and the Netherlands about whether or not they can afford a welfare state any longer.

Once again, Generation Z will be the ones left behind. While paying Europe’s high taxes from day one—if they find a job—they are increasingly at risk of being left out of the benefits that those taxes are supposed to pay for.

To be fair, all is not doom and gloom for Europe’s young. Youth unemployment so far into the 2020s is about five percentage points lower than it was in the early years of the 2000s. But first of all, 15% unemployment is still outrageously high, and second, many countries have reformed their unemployment and job-training programs in such a way that it is increasingly onerous to remain on jobless benefits.

This would all be fine and dandy if it were not for the fact that when our young actually do get a job, it is increasingly a job they will be forced to stick with. For my generation, low-paying jobs in the service sector were entry-level positions where you got your first labor market experience. It was an experience that allowed you to pursue better opportunities.

For Gen Z’ers, the door to that pursuit is closing—and the reason is that the economy overall is standing still. It did not have to get to this point, and the future does not have to be one of endless industrial poverty. But if things are going to change, that change must involve the political leadership, from Brussels to most of the member states.

Before we look at some numbers showing just how serious the situation is, let me emphasize that GDP growth is not a fix-all solution to all our economic problems. It is, however, a necessary foundation for productive solutions; when the cake is growing, every one of us will get a bigger slice without having to cut into our neighbor’s slice.

In plain English: strong economic growth generates plenty of jobs, it generates better incomes for all jobs, and it opens far more entrepreneurial opportunities than a stagnant economy does. Consumers get more to choose from; workers steadily make more money; inflation stays low.

To drive home the gravity of the present situation in the European economy, let me present some numbers that show that we did not just now wake up to this problem; on the contrary, it has been long in the making.

Let us compare real GDP growth rates for 21 European countries from 1971 through 2019. The countries are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden. These are chosen strictly based on access to unbroken time series of data from the United Nations national accounts database.

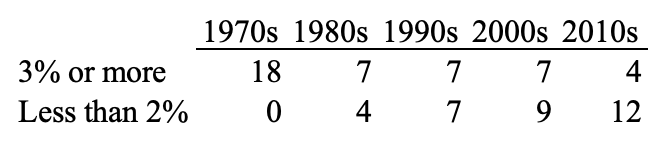

In the 1970s, 18 of these 21 countries enjoyed an inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate of 3% or more per year. That is a high growth rate, basically guaranteeing that all workers will experience tangible improvements in what their paychecks can do for them. Those who are new to the labor market are faced with an abundance of options. Households experience steady improvements in their finances.

In the 1980s, our 21 European countries were still doing relatively well, but the first cracks in the prosperity machine were making themselves known. Only seven of the aforementioned 21 countries enjoyed 3% or more in GDP growth per year, with ten countries in the 2-3% range.

That segment is still tolerable, so to speak; the problems start emerging when GDP growth slips below 2% per year after inflation. For reasons that I explain in chapter 3 of Industrial Poverty, an economy that does not grow at 2% per year cannot produce enough resources—goods, services, jobs, household incomes, profits, tax revenue, investment capital—to maintain the general standard of living over time.

Sadly, the trend of economic stagnation that began in the 1980s did not stop. Table 1 reports the number of countries in the 3%+ and the less-than-2% groups:

Table 1

Here is another way of looking at the same trend of economic stagnation:

A long-term slowdown in GDP growth has profound consequences for young workers. They have to work harder to achieve the same improvements in standard of living as their parents saw through their careers in the labor force. When the economy gets stuck at growth rates well below the 2% threshold, they actually fall behind their parents’ generation—no matter how hard they work.

This is pretty much the situation that Generation Z is stuck in today—and the outlook for the near future is not better. According to Eurostat, since 2020, the real GDP growth rate for the 27 EU member states has averaged 1.3% per year. As mentioned earlier, the European Commission predicts that the EU economy will continue to grow at this rate at least through 2027.

I should add that this is under ‘ideal’ circumstances, where there are no tax hikes, no new sprawl of regulations across the European economy, and where deficit-ridden governments do not resort to growth-crippling austerity to balance their budgets.

As much as I would like not to, I still have to raise this warning: with just a little bit of bad luck, the EU economy could end up smaller in January 2030 than it was in January 2020. I don’t think I have to spell out what this means for the economic opportunities for Europe’s struggling youth.

It did not have to get to this point. None of this was inevitable. All of it was preventable. The fact that Europe’s political leaders have allowed the very foundation of their continent’s prosperity—a growing economy—to falter is a heavy indictment of them and their lack of leadership.

The fact that their negligence has potentially doomed an entire generation to a life in industrial poverty is downright immoral.