As an analyst of, among other things, the market for U.S. debt, I am always cautious about issuing crisis warnings. Such statements can easily be misinterpreted, exaggerated, and even purposely distorted, to the point where it starts affecting the market.

Therefore, what I am going to say here must be read in a dispassionate voice. There is no need for anyone to panic about a U.S. debt crisis; all I am doing here is point to two market trends that, when coinciding as they do now, tell us that investors are uneasy.

That uneasiness could subside, or it could become a threat to the stability of the U.S. debt market.

With this caveat in mind, let us go back to last week when there was a little bit of turmoil on the market for U.S. Treasury securities. It was not dramatic, and it could easily be mistaken for the usual ups and downs of the market. But it was there, and it was in part brought about by the U.S. Treasury, which on January 31st revealed its borrowing plans for the coming months. In its Quarterly Refunding Statement, the Treasury explained that it

plans to increase the auction sizes of the 2- and 5-year [notes] by $3 billion per month, the 3-year by $2 billion per month, and the 7-year by $1 billion per month.

There are also plans to sell more 10-year notes and 30-year bonds.

After the Treasury’s announcement, there was a surge in demand for Treasury notes in those classes. For technical reasons, this surge manifested itself in falling yields: when the price of a debt security increases, its yield declines.

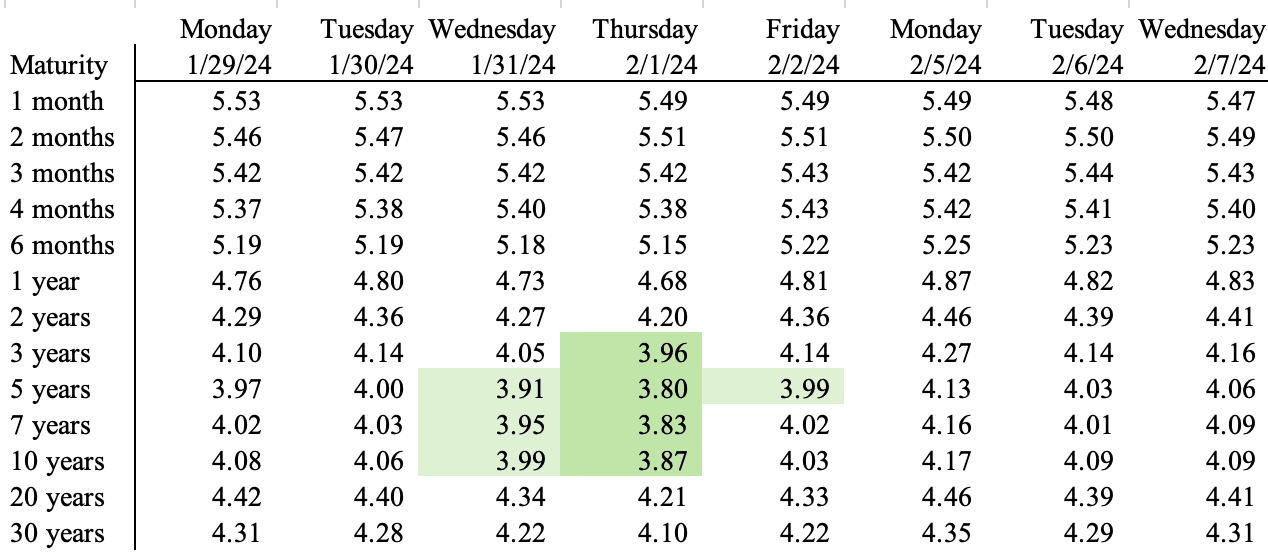

The decline in yields is important, not because it happened but because it was a temporary event. The green markings in Table 1 highlight the yield drops that followed immediately upon the Treasury’s announcement:

Table 1

The temporary nature of the yield drops is characteristic of a speculative intervention in the market. Some investors decided that it was a good time to take positions in the maturity classes under which the Treasury is going to increase supply in the near future.

Normally, these speculative waves would last longer; last spring, when the Federal Reserve announced a program to help failing banks, the speculative splash lasted for over a week. This news is less dramatic, but it comes with a concrete fiscal value and with well-defined market terms. Therefore, the brief nature of this episode is curious.

There is an explanation for its short duration: there is an underlying trend of rising debt yields, and this trend was stronger than the speculative intervention after the Treasury’s announcement of revisions to its debt management. By Tuesday, February 6th, yields had returned to where they were on the preceding Tuesday, a day before the Treasury’s announcement.

The resiliency of the current yields is a hint that investors are concerned about the future of the market for U.S. debt. In addition to the upward pressure on interest rates that likely will result from the shift in the Treasury’s debt issuance policy, debt yields are trending slowly upward over the longer term.

This trend began in late December when it ended a longer trend of falling yields. After topping out around 4.8-5.3%, the yields on longer-maturity Treasury notes and bonds, i.e., those with a life span of 2-30 years, fell from late October until Christmas, when they bottomed out around 3.8-4.2%. Since then, yields have been ratcheting upward, currently hovering in the 4-4.5% bracket.

The upward trend in U.S. debt yields is slow and undramatic, but it is persistent enough that the speculative infusion into the market on January 31st did not break it. On the contrary, the upward trend absorbed the shock with aplomb and seems poised to continue. In fact, it is now pulling auction yields with it. Some examples from the U.S. Treasury’s database on debt auctions:

At the February 7th auction of the ten-year note, the Treasury ended up paying a median yield of 4.04%. This is up from 3.96% in January.

We could interpret these movements as marking an end to the decline in yields from last fall, rather than a new trend of slowly rising yields. This would be a viable explanation, were it not for the fact that another, rarely discussed variable called the ‘tender-accept ratio’ has trended in a way that supports the impression of market uneasiness.

The tender-accept ratio is the ratio of money offered at debt auctions to the value of the debt sold. To take one example, at the aforementioned auction for ten-year notes, investors offered $110.5 billion for the $45.1 billion in debt that the Treasury auctioned off. This means that there were $2.45 tendered for every $1.00 of debt sold—the tender-accept ratio, T/A, was 2.45.

The compound form of the T/A ratio, i.e., the ratio that applies to all outstanding U.S. debt, has declined for three weeks in a row. On January 16th and 17th, it stood at 2.636; as of February 7th, it had fallen to 2.533.

In plain English, this means that for every auction that has been held over the past three weeks, investors in the Treasury market have offered fewer and fewer dollars per $1 in debt sold.

When investors tender less money at the debt auctions over an extended period of time, it signals concern from investors about the prudence in investing in U.S. debt. So far, the downward trend in the T/A ratio has been slow and undramatic—much like the upward crawl of market yields.

However, when these two trends are at work simultaneously, it is time to pay close attention to the market. If investors end up losing confidence in U.S. debt, they will signal that in the form of demands for higher yields and by committing less money to buying the debt.

Let me emphasize, again, that these two trends are weak and have not been at work for very long. This tells us that there is no immediate risk of a U.S. debt crisis. With that said, though, the two trends are at work, and they have been so for long enough that it is time for Congress to consider what happens down the road if the debt market continues in the same direction.