While the media is frenzying about the latest inflation numbers—which as I explained yesterday are not much to frenzy about—there are movements in the U.S. debt market that are a much bigger reason for worry.

The worry is centered around the so-called yield curve for U.S. government debt. It shows the latest market interest rates on Treasury bills (1 month to 1 year maturity), notes (2-10 years), and bonds (20 and 30 years). This curve is set by buyers and sellers trading U.S. sovereign debt on a daily basis.

Normally, the yield curve slopes upward, with interest rates being lower on short-term debt and higher on long-term securities. This makes sense: as a buyer, you lend your money to the U.S. government and therefore expect a risk premium if the loan runs over a longer period of time. However, since late 2022 the U.S. yield curve has been inverted, which means that it slopes downward and investors get less return if they lend their money for a longer period of time.

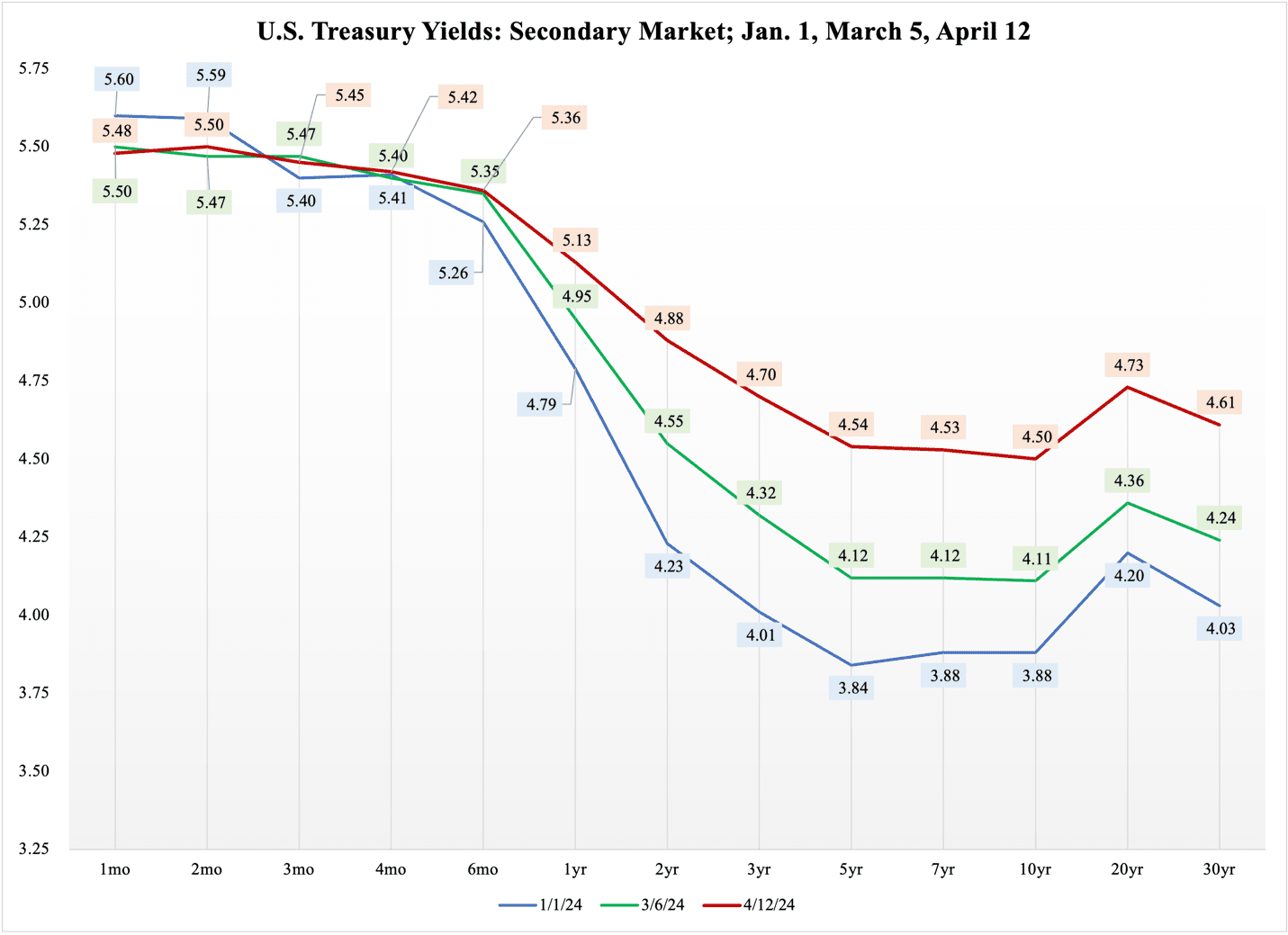

Recently, the yield curve has slowly begun to flatten, but not the ‘right’ way. On a sound debt market with an inverted curve, short-term debt would fall while long-term debt rises. But this is not the case for U.S. government debt. Figure 1 shows three examples of the yield curve, from January 1st to April 12th, and it shows interest rates rising in the long end while the short-term rates remain unchanged:

Figure 1

At the start of the year, the notes and bonds, with maturities of two years and more, paid between 3.84% and 4.23%. On April 12th, the same maturity classes pay between 4.5% and 4.88%. This increase has happened while the maturities of 1-6 months have remained largely unchanged.

On any day, a trend like this in the sovereign debt market suggests that investors are getting uneasy with the reliability of the debt they are buying. Put simply, they want higher risk premiums to lend money to the government over a longer term. But this is not all that is happening in the U.S. debt market: the market-driven rise in longer interest rates is accompanied by a shift in Treasury debt-management policy.

As part of a policy to strengthen stability and predictability in the cost of the federal government’s debt, the Treasury has decided to change the maturity profile of its debt sales, from short to longer. This reduces the Treasury’s exposure to unpleasant swings in interest rates and—at least in theory—helps protect U.S. taxpayers from having to wake up one day to a higher tax bill.

This policy shift has two effects on the yield curve:

So far, we are only seeing the latter; the former has yet to happen. The fact that interest rates are rising on long-term debt without the corresponding decline in the short end is worrisome.

Some analysts would point out that the short-term rates are consistent with the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate policy. They have continued to keep their federal funds rate above 5%, which would make it seem natural that short-term rates on U.S. debt would remain at the same level. If we cherry-pick data, we can certainly find such a correlation, but the rates on short-term maturities are still subject to the laws of supply and demand. A decline in supply at a given demand inevitably pushes prices upward—which, again, by definition means lower interest rates on those maturities.

The Treasury has indeed cut the supply of new short-term debt at its recent auctions. For debt with a maturity of 4-8 weeks, the volume sold has fallen by 11-26% over the past month; for debt with a three-month maturity, the volume is down by 6%.

Meanwhile, the volume sold in the longer end is up: after having reduced sales of two-year notes at the January auction, in February and March (no April auction yet), the Treasury increased the volume sold by 8% and 11%, respectively. The volume sold under the 10-year note went up by a whopping 86% in March and 88% on April 10th.

These increases in sales of long-term debt should depress prices and raise interest rates on those maturities—which is exactly what we see happening in the yield curve in Figure 1. However, the rise in long-term interest rates cannot be solely explained by this shift in Treasury policy; if it were, we would again see the corresponding decline in short-term rates.

Are long-term yields affected by the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate policy, just as short-term yields are influenced by it? No, this is not the case, at least not primarily. If it were, the market would suddenly expect that the Fed will keep its federal funds rate elevated above 4% for 5-30 years into the future.

Treasury yields are much more affected by expectations and short-term moves in the market than they are by long-term outlooks. This holds true even for long-term debt which matures many years into the future. As I have reported recently, the dominant expectations in the debt market are related to concerns among institutional investors that the U.S. government is losing control over its own debt. Therefore, so long as Congress refuses to do anything to address its $2+ trillion deficit, we will see rising interest rates, as well as other signs of growing investor worries in the market for U.S. debt.