When the European Central Bank recently cut its policy-setting rates, expectations briefly surfaced that the Federal Reserve would do the same. I did not share those expectations; in fact, I abandoned any hope for a U.S. rate cut months ago. The reason is a combination of stubborn inflation and the complete lack of fiscal initiatives from Congress.

Since the winter and the spring when U.S. rate cut expectations flew out the window, inflation has come down to tolerable but not long-term acceptable levels. According to the latest numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. producer prices are increasing again after falling for 13 straight months; the producer price index (PPI) inflation rate is low at 0.5% in May, but the upward trend suggests that the chance for further decline in consumer prices is over, at least in the short term.

This means that the U.S. economy is stuck with consumer price inflation (CPI) around 3.3%. A decline in economic activity would put a damper on both PPI and CPI inflation, but no such decline is in sight. Therefore, as far as inflation is concerned, the Federal Reserve is unlikely to execute any rate cuts this side of Halloween.

Another big reason why there will probably not be any rate cuts in the near future is the perennially sordid state of the federal government’s budget. It is a major reason why U.S. interest rates remain high generally.

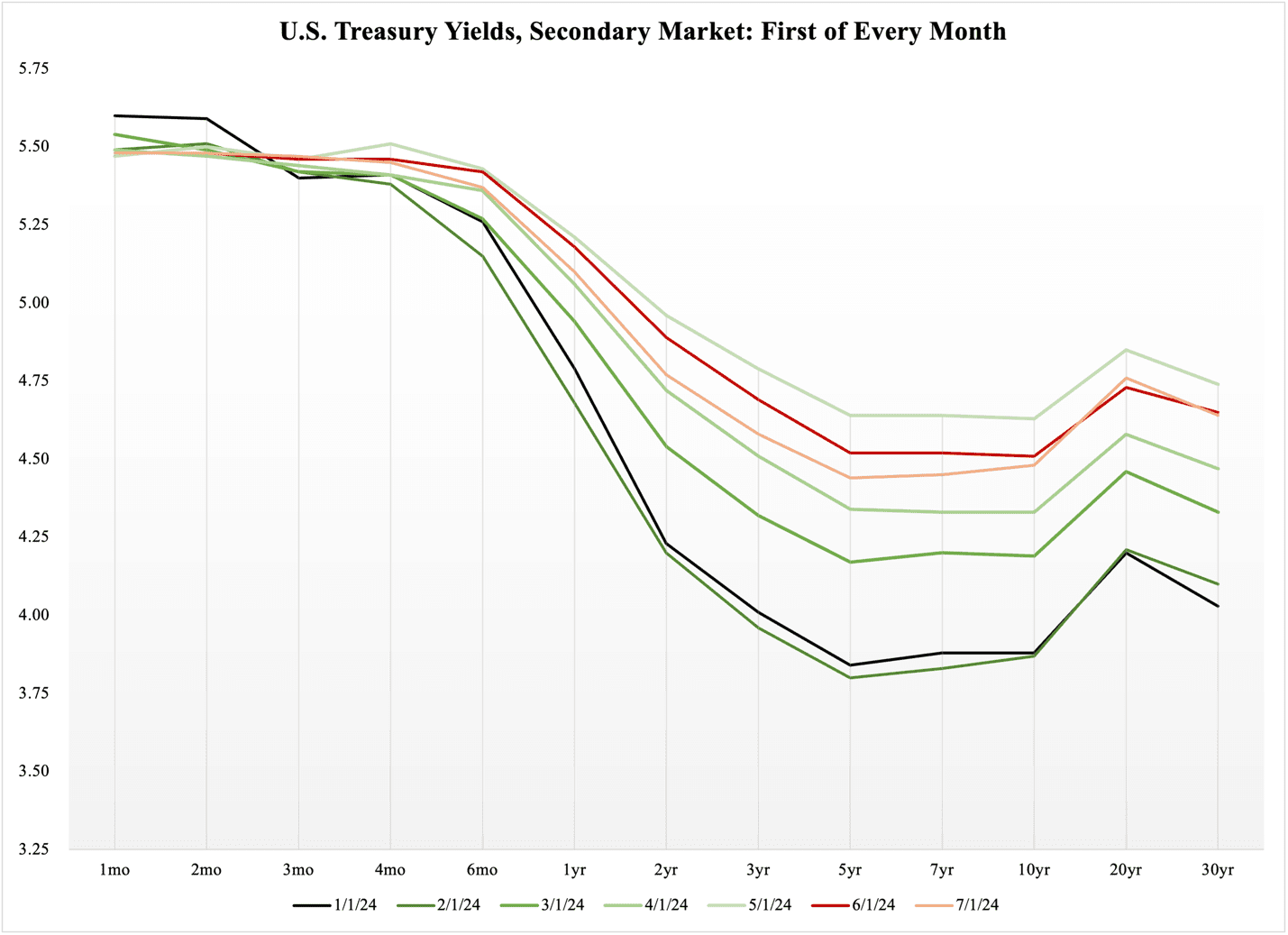

There have been some weak tendencies toward lower interest rates. Late last year, market yields on longer-term U.S. debt came down about one percentage point, from the 4.7-5.2% bracket to 3.7-4.2%. There were some expectations that this would pull down short-term yields as well, but that never happened. Instead, in the first weeks of 2024, yields on long-term debt began rising again. Their increase was slow-paced, but in early May they were back in the 4.5-5% neighborhood.

In May and June, another yield decline took place; toward the end of June, market yields had fallen about 0.5 percentage points, though this applied only to maturities of 2 years and more.

It looked like the downward trend was going to continue, but it did not. Two days into July, yields on U.S. Treasury securities maturing in two years or more, are parked in the vicinity of 4.5-5%, with shorter maturities of one month to one year paying up to 0.5 percentage points more.

If there is one thing we can learn about the U.S. debt market from the first half of this year, it is that there is no pressure in the debt market for yields to come down. As Figure 1 shows, the yield curve has drifted upward since the beginning of the year:

Figure 1

With long-term yields slowly rising, the only way that this inverted yield curve will ever get back to ‘normal’ again is if the securities that mature in two years or longer pay more than 5.5%. This would be a frightening scenario, and while unlikely, it is far from impossible. If the U.S. is hit by a fiscal crisis, debt market investors will quickly raise demands for yields in the 7-10% bracket.

The current yields do not reflect any imminent risk for a fiscal crisis, but they do incorporate some level of concerns about acute fiscal trouble for the U.S. government. The market yields are constantly 0.25-0.3 percentage points higher than the yields at Treasury auctions. This means that when the U.S. Treasury sells new debt, it puts the fresh bills, notes, and bonds out into a market that already from the start thinks it is not paying investors enough.

If investors were flocking to U.S. debt, market yields would be on par with, or even lower than auction yields. These would be ideal conditions for the Federal Reserve to cut its policy-setting funds rate, but those conditions are nowhere to be found right now. As long as the market is expressing a preference for the current rates, or even slightly higher ones, it would be unwise for the Fed to make any rate cuts.

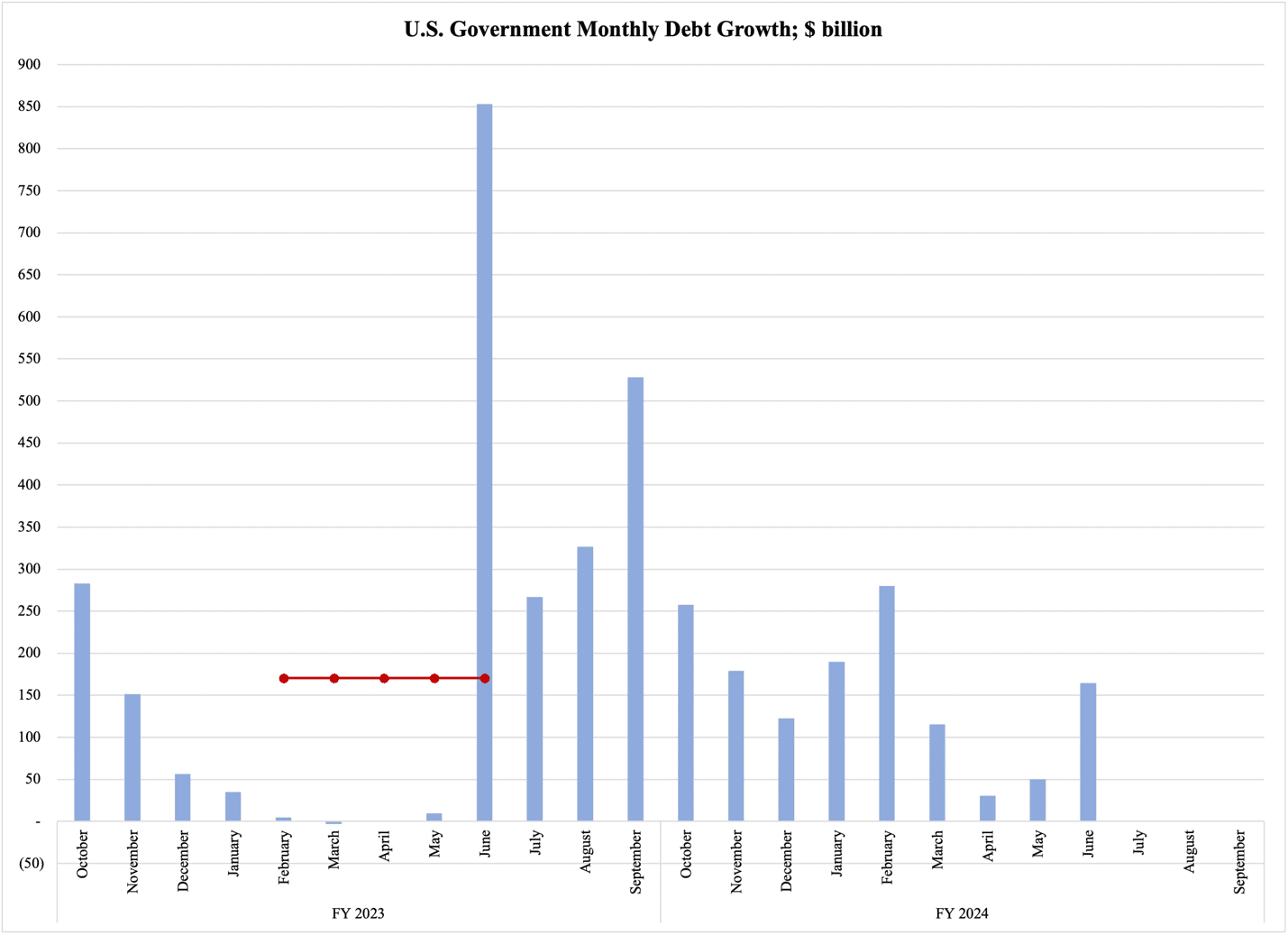

Although this is practically never discussed in political circles, the reason for the elevated pressure on U.S. debt yields is the fact that Congress continues to pay at best passing interest to the debt. Figure 2 reports the monthly growth in the federal government’s debt since the beginning of the 2023 fiscal year (October-September); there is an oddity with the debt figure for June 2023—see comment below the figure:

Figure 2

During the spring of 2023, Congress was locked in an impasse over the debt ceiling, i.e., the statutory limit on how much money the federal government can borrow. Once that was solved at the end of May, the Treasury had to ‘catch up’ by selling extraordinary amounts of debt.

The red line illustrates the June debt growth as borrowing per month during the debt ceiling impasse. Viewed this way, the $853 billion June figure comes across as much less conspicuous.

In total, the debt grew by $2,512 billion during the 2023 fiscal year. So far into FY 2024, the debt has grown by $1,389 billion; assuming the same monthly pace for the remaining three months of this fiscal year, the total tally would stop at $1,853 billion. However, experience from past fiscal years would suggest that there will be a significant uptick in borrowing as we get into August and September; the final number for FY ’24 will in all likelihood be approximately $2,100 billion.

What we can say with relative certainty is that the federal government will not borrow more than $2,500 billion in FY ’24. This means a decline in annual borrowing—and therefore a decline in the budget deficit—which at first glance is cause for celebration. However, it is of little if any consequence for the U.S. government’s fiscal future that the debt fluctuates within a couple of hundred billion dollars from year to year as long as the annual amount borrowed exceeds $2 trillion. Roughly speaking, this means that Congress has doubled its annual borrowing from the 2010s—without showing any concerted political desire to bring the monumental deficit under control.