In its EuroIndicator published on December 7th, Eurostat reported that

seasonally adjusted GDP decreased by 0.1% in the euro area and remained stable in the EU, compared with the previous quarter … Compared with the same quarter of the previous year, seasonally adjusted GDP remained stable in both the euro area and the EU

Eurostat also reported that employment grew in 14 member states, though only three states— Croatia, Lithuania, Malta, and Spain—added more than 1% of new jobs. Employment fell in 13 states, with Estonia and Ireland being hit by a decline in excess of 1%.

These numbers generally point in the same recessionary direction that I reported back in August, and Eurostat’s numbers are not even the ‘worst’ ones available. They report seasonally adjusted figures, which means that Eurostat has modified the numbers to neutralize the effect of seasonal variations in the economy.

It is a popular and perfectly respectable statistical technique, but every modification of raw data puts more distance between the number published and the reality it is supposed to report on. If this is taken too far, statistical analysis becomes pointless.

If we want to get a closer look at the economy, we need to do what I did back in August, namely switch to so-called unadjusted data. These are, essentially, the raw data that Eurostat collects for its national accounts database. Based on these figures, we can calculate year-to-year growth numbers and get a highly accurate picture of where the European economy is in terms of the looming recession.

There is little doubt that the situation for the European economy is worse than the Eurostat report suggests. To start with, the GDP for the 27-member EU declined by an inflation-adjusted -0.13% in the third quarter over the same quarter last year.

This is the first quarter with a recorded annual GDP decline since the artificial economic shutdown in 2020-2021. This means that it is, technically speaking, not an indicator of a recession; for that to happen, an economy needs two consecutive quarters of declining GDP. However, the number follows a string of weakening growth numbers: in the four latest quarters, the GDP for the European Union has weakened from 2.56% in Q3 of last year to now actually declining.

For this reason, it would come as no surprise if fourth-quarter GDP falls by more than 1%.

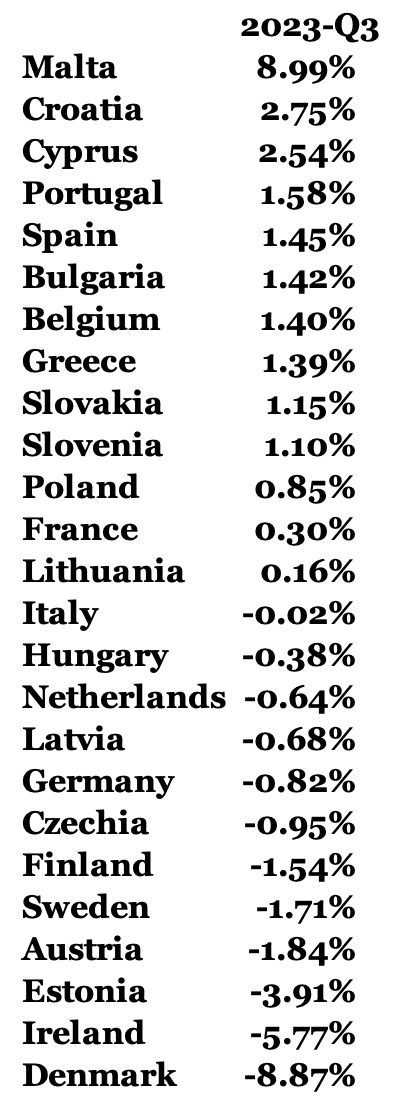

Many member states also exhibit signs of a recession, or have already entered one. Of the 25 states that have reported GDP numbers for the third quarter (the slackers being Luxembourg and Romania), 13 had a growing economy and 12 saw it shrink:

Table 1

Eleven of the 12 member states with a declining GDP in Q3 also had negative growth in Q2. The Czech economy has now been contracting for four quarters in a row, while Estonia has had a declining GDP for five quarters. However, the positive news for the Czech Republic is that they seem to have reached the bottom of the recession; their most recent GDP growth rates have been as follows:

It is too early to definitively say that their economy is on the rebound, but their overall unemployment numbers, which have fluctuated between 2.3% and 2.9%, add to the picture of an economy that may be improving again.

The Hungarian economy follows a similarly encouraging pattern, with the following recent growth rates

In other words, only three quarters with declining GDP, with a pattern that strongly indicates a V-shaped recession, so to speak. The fourth quarter will likely be modestly positive, an outlook that is reinforced by Hungary’s relatively low and stable unemployment rate: since January this year, it has varied between 3.8% and 4.1%. Although the higher number was recorded as recently as in October, it is likely lagging GDP by one or two months; a modest GDP growth rate in the fourth quarter will bring unemployment down below 4% early in 2024.

On the more troubling side, German GDP now has two consecutive quarters of negative growth—in other words, Europe’s largest economy is now officially in a recession. With -0.4% in Q2 and -0.82% in Q3, the decline is by no means alarming, nor is the steady-as-she-goes unemployment rate of 3.1% in October. However, with the same lag in unemployment and the visible negative trend in German GDP (the growth rate has been weakening since Q1 of 2022), it is only a matter of two months before the German unemployment rate starts rising.

Other countries with a recessionary GDP and an outlook similar to the German:

Austria, where GDP fell by -1.33% in Q2 and -1.84% in Q3;

Finland, whose GDP numbers were -0.55% in Q2 and -1.54% in Q3;

Netherlands, with -0.16% in Q2 and -0.64% in Q3; and

Sweden, with -1.42% and -1.71%, respectively.

The Swedish economy exhibits many signs of weakness; for one, their unemployment rate in October is the third highest in the EU. Spain tops the league at 12%, followed by Greece at 8.7% and Sweden at 7.4%.

We should not forget that 13 EU states had a growing economy in Q3, but we should also not ignore that only three of those had a GDP growth above 2%. The Spanish economy is a case in point in this group: its economic growth is weakening every quarter; in Q2 it barely exceeded 2%, only to land at 1.45% in Q3.

As I have explained before: all the recession bells are ringing in Europe. It is time for lawmakers all across the union to respond accordingly.