Yesterday, I reported that interest rates in the U.S. economy have turned upward again, after declining for approximately two months.

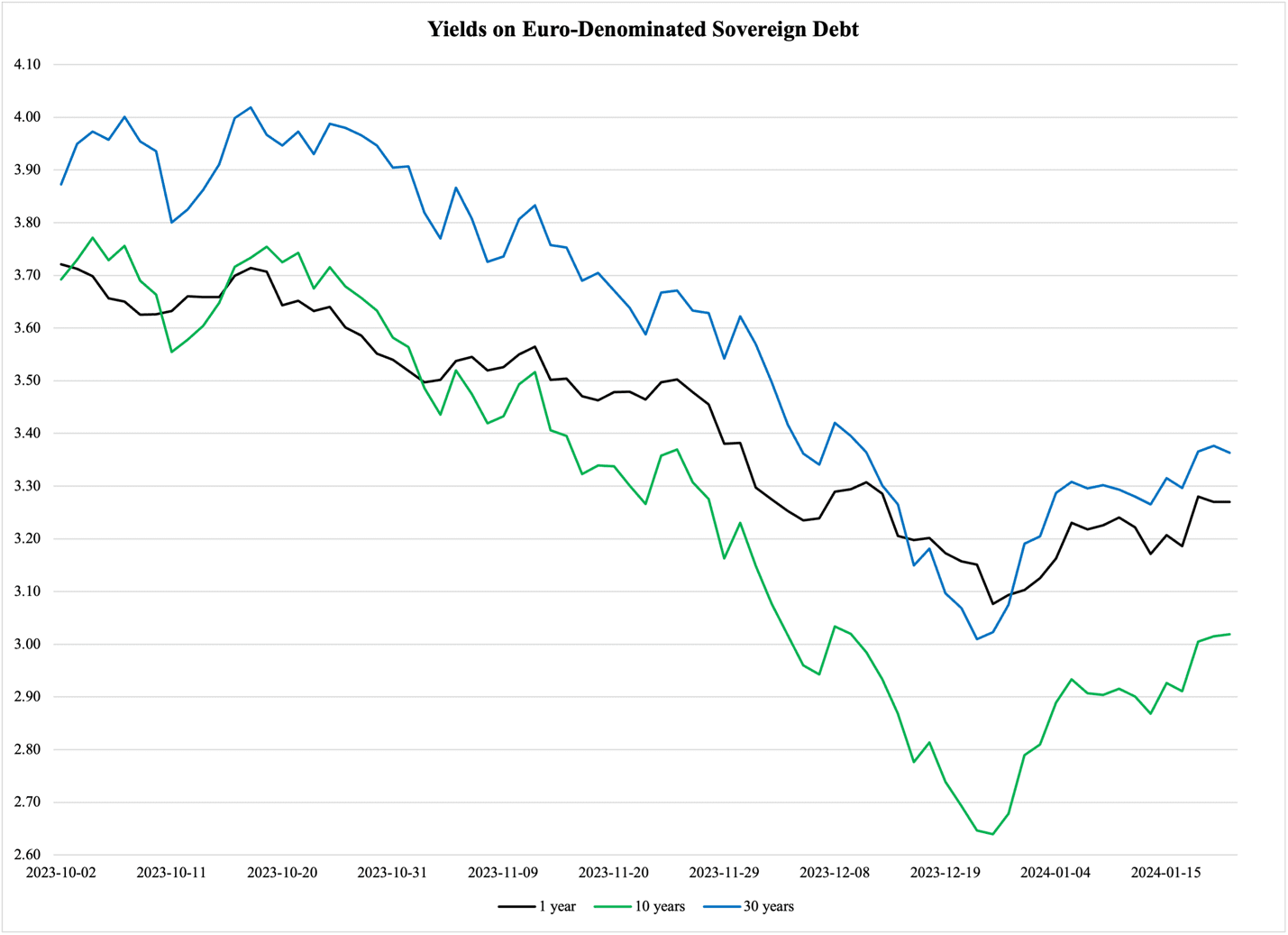

Today, I have to add to the bad news: interest rates are rising in Europe as well. Figure 1 has the story, covering the one-year, the ten-year, and the 30-year treasury securities denominated in the EU:

Figure 1

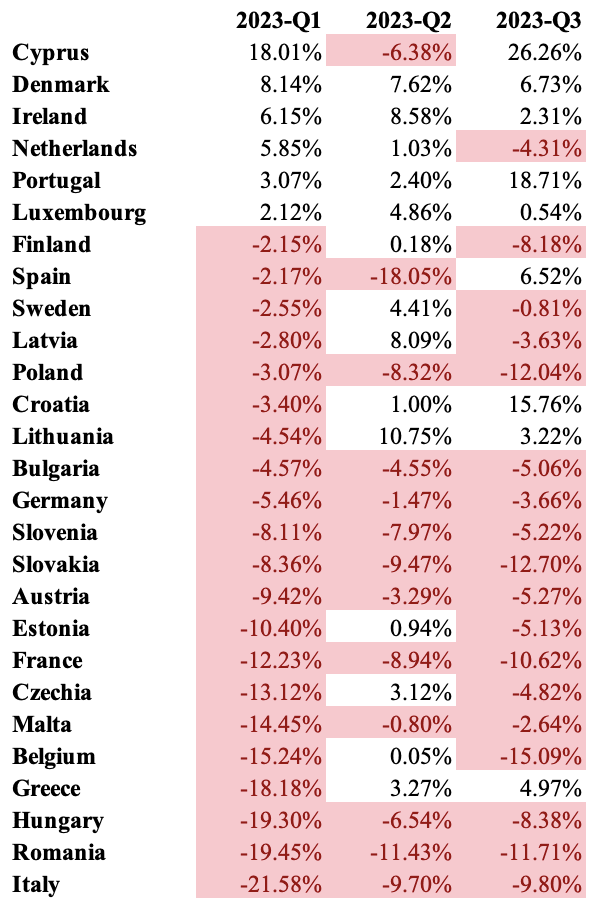

As I explained yesterday, we have good reasons to believe that the uptick in interest rates in the U.S. debt market is related to growing worries among investors over the fiscal sustainability of the U.S. government. This reason cannot be directly transplanted to the EU market. While there is no doubt that Europe is at the beginning of a recession, the fiscal picture of the euro zone members is relatively complicated. Table 1 reports budget deficits as a percent of total government spending in all the EU member states. In the first quarter of 2023, only six governments ran surpluses; in the second quarter, it was 14 of them. The third quarter again saw a deterioration in fiscal balances, with nine countries in the surplus group:

Table 1

A majority of the EU member states as well as a majority of euro-zone members are struggling with deficits in their government finances. However, the fiscal situation is too complicated to have the same direct influence over yields on sovereign debt in the euro zone as the straightforward fiscal problems of the U.S. government have on the dollar-denominated market.

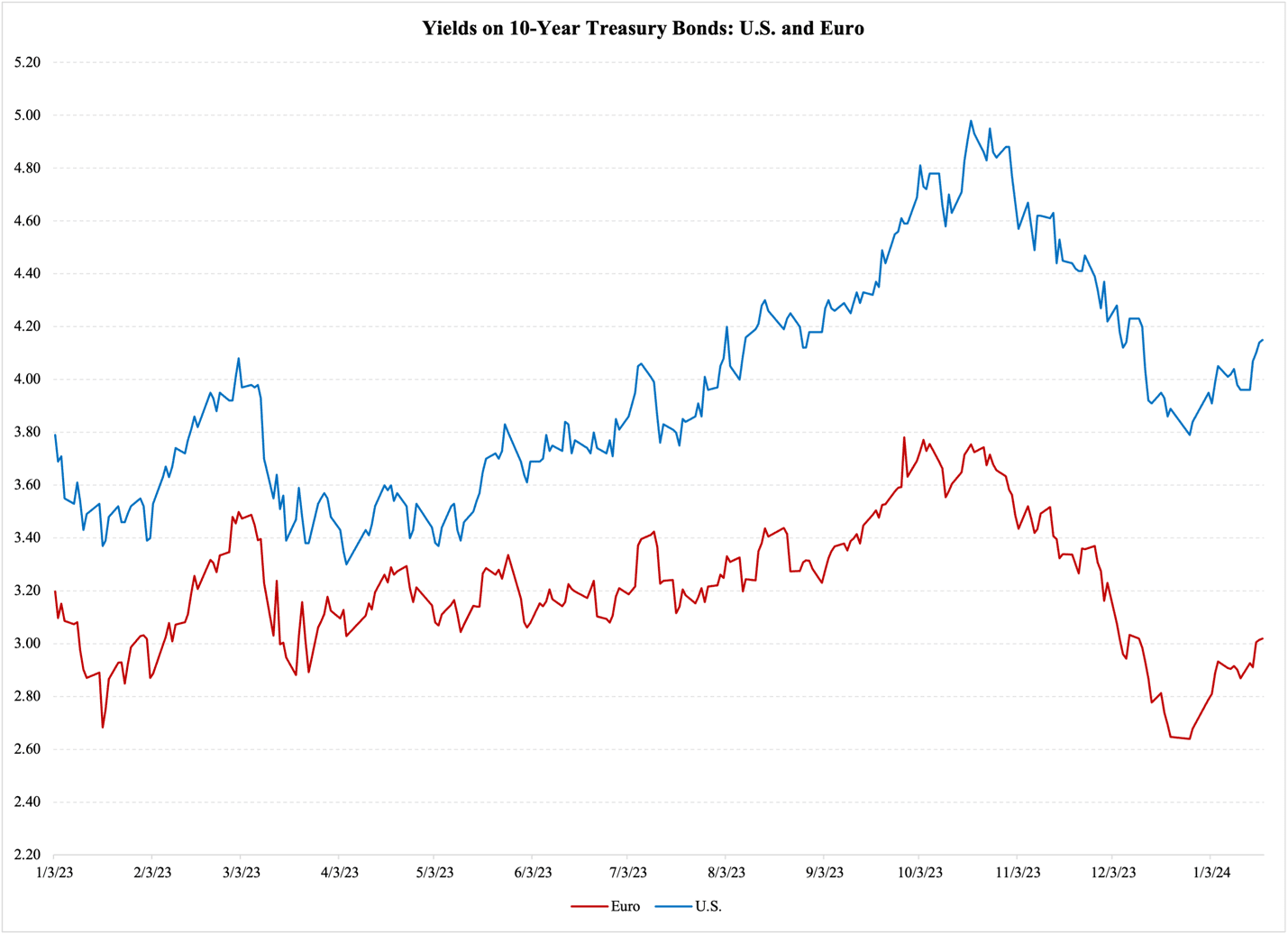

The reason for the recent rise in yields on euro-denominated debt is instead to be found in the close correlation between European and American sovereign debt markets. Figure 2 explains how the euro-denominated 10-year treasury security (red line) varies with the same debt instrument issued by the U.S. Treasury (blue). The correlation is exceptional:

Figure 2

It is not difficult to explain this close correlation. The American and European markets are integrated as far as possible without having the same currency; any difference in yield is immediately exploited by speculators.

Upon close examination, it is practically impossible with publicly available data to determine which market leads which—in other words, if European yields follow American yields, or the other way around. We could answer this question with an intricate analysis of the flows of money across the Atlantic, as well as the precise timing of yield changes. However, such analyses require access to proprietary data of a high degree; there is a much simpler way to demonstrate which of the two markets leads the other.

Central bankers all over the world will readily admit that the American central bank, the Federal Reserve, is a world-leading policy-making institution. The main reason is in the size of the supply of U.S. dollars, which, e.g., accounts for 60% of the world’s central bank reserves. The share is slowly shrinking, but the dollar remains the dominant reserve currency of the world.

Another reason for the Fed’s dominance is in the size of the market for U.S. debt. With $34 trillion in total debt and $5.2 trillion maturing in a year or less, the United States accounts for close to one-third of the public debt in the world. Although the debt is technically under the jurisdiction of the United States Treasury, the Federal Reserve is the influential institution as far as debt yields are concerned.

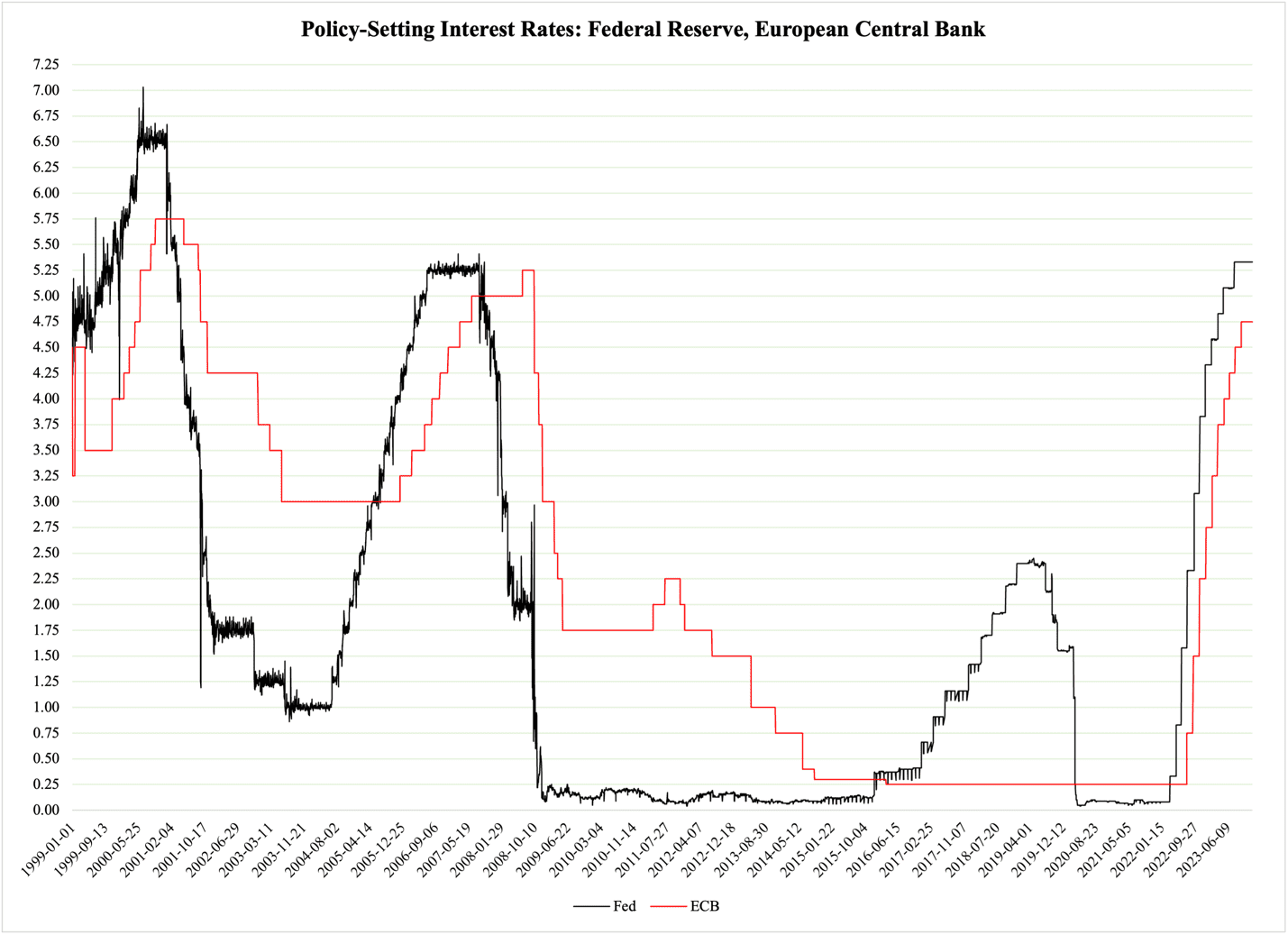

With its dominant position, the Federal Reserve tends to lead the way when it comes to interest-rate setting. One of the best images of this leadership is reported in Figure 3, where the federal funds rate, i,e., the Fed’s policy-setting rate (black), is compared to the lead policy rate of the ECB (red):

Figure 3

With few exceptions, the ECB has followed closely behind the Federal Reserve both in raising and lowering its interest rates. Given this relationship between the two central banks, it is fair to conclude that the markets for sovereign debt yield are related in the same way. This helps us explain the rise in rates at the end of Figure 1 as caused by rising yields on U.S. government debt.

This close dependency of the European debt market on its U.S. counterpart is good for investors, but not necessarily good for the two economies. On the U.S. side, where the rising rates can be linked to worries about the fiscal solvency of the government, rising rates will help transition the economy from its mature growth period into a slowdown, perhaps even a recession. At the same time, if the higher rates are interpreted as precisely what they are, namely a signal from the market for sovereign debt that investors are worried about the government’s fiscal solvency, then there is a chance that Congress can start working on a plan to stabilize their government’s budget.

Depending on how such a stabilization is executed, it can help alleviate,—or aggravate—a recession. In the former case, interest rates will decline again as a direct result of Congressional anti-deficit initiatives.

The situation is more troubling on the European side. If the yields on euro-denominated sovereign debt stay elevated or even continue to rise, it will be an unmitigated detriment to the European economy. While the U.S. Congress can do something about rising interest rates, there is nothing that any legislature in Europe could do to alleviate the repercussions of higher interest rates.

This point, again, is made under the assumption that no other variables influence euro yields the way U.S. yields do. As one example of what this means for the European economy: the stronger the U.S. influence on the euro-denominated debt market is, the more difficult it will be for the European Central Bank to lower interest rates in the euro zone by expansionary monetary policy.

In short, when it comes to interest rates, Europe is more or less at the mercy of what America’s fiscal and monetary policymakers do. This can be good when American policies help bring interest rates and inflation down and raise GDP growth.

It can also be bad: if Congress ignores the signs of unease in the debt market and thereby brings about a fiscal crisis, then the close tie between American and European markets is a surefire way to bring an American debt crisis to Europe.