On May 28th, Eurostat—the EU’s own statistics agency—published a report on the family benefits that EU member states pay out to their residents. The numbers, which are from three years ago, are staggering:

In 2021, EU countries spent an average of €777 per person on family benefits, up from €561 in 2011. In total, €347 billion was spent on family benefits in 2021, an increase of 41% compared with 2011 (€247 billion).

This means that the average family of two parents, two kids in Europe receives €3,108 per year in tax-paid family benefits. Given that in 2021, the same average family earned €53,284 after taxes, these benefits may not seem all that significant.

However, if one of the parents earns the average income and the other one-third of the average, their combined net-tax earnings fall to €38,746. The average package of family benefits now equals 8% of their net-tax earnings.

Put differently, if the family wanted to provide for themselves instead of getting the average family benefits, the parent with the lowest income would have to earn a 26% raise—after taxes.

When viewed this way, tax-paid benefits take on a very different meaning. Since they are work-free income, they discourage workforce participation beyond the minimum needed for a person to qualify for the benefits. The bigger the benefits are relative to the family’s net-tax income, the greater the leap into the workforce that the parents have to make in order to replace those benefits.

That leap, in turn, cannot simply be aimed at replacing the benefits; using the numbers above, earning a 26% net-tax raise will not improve the family’s bottom line. All that will happen is that one parent now works longer hours or has to take on more qualified responsibilities at work—or a combination of both.

To many workers, breaking even while having to work more (quantitatively or qualitatively) does not make life better. The family would have to see an improvement of its finances, and the improvement would have to be big enough to compensate for the increased absence from home that comes with longer hours, and the increased stress that goes with greater professional responsibilities.

Economists have spent considerable time researching the causes and effects of labor supply. Among the most established findings is this very trade-off: workers do weigh increased income against decreased quality time with family and friends. This means that two demographics within the workforce tend to have the greatest reservations against working more and accepting promotions that come with greater responsibilities.

The first of them is the high-income earner who faces very high marginal income taxes. When taxes take away half or more of the last earned euro, the incentives for highly paid physicians, engineers, accountants, bankers, and other professionals to put in an extra hour of work are weak at best. This demographic group shoulders heavy tax burdens in most European countries.

The second demographic consists of lower-income earners who know that their family benefits overwhelmingly get better the less money they make. It becomes difficult, if not impossible, for workers to elevate themselves from the dependency on government; finding a job that can raise your income by 40-50% after taxes is difficult, to say the least.

Welfare states across Europe have different configurations of their family benefits, including the eligibility criteria and the progressivity of their income taxes. However, since most of them are designed for the purpose of income redistribution—to give more to those who have less and vice versa—the problem discussed here applies to a varying degree to most EU members.

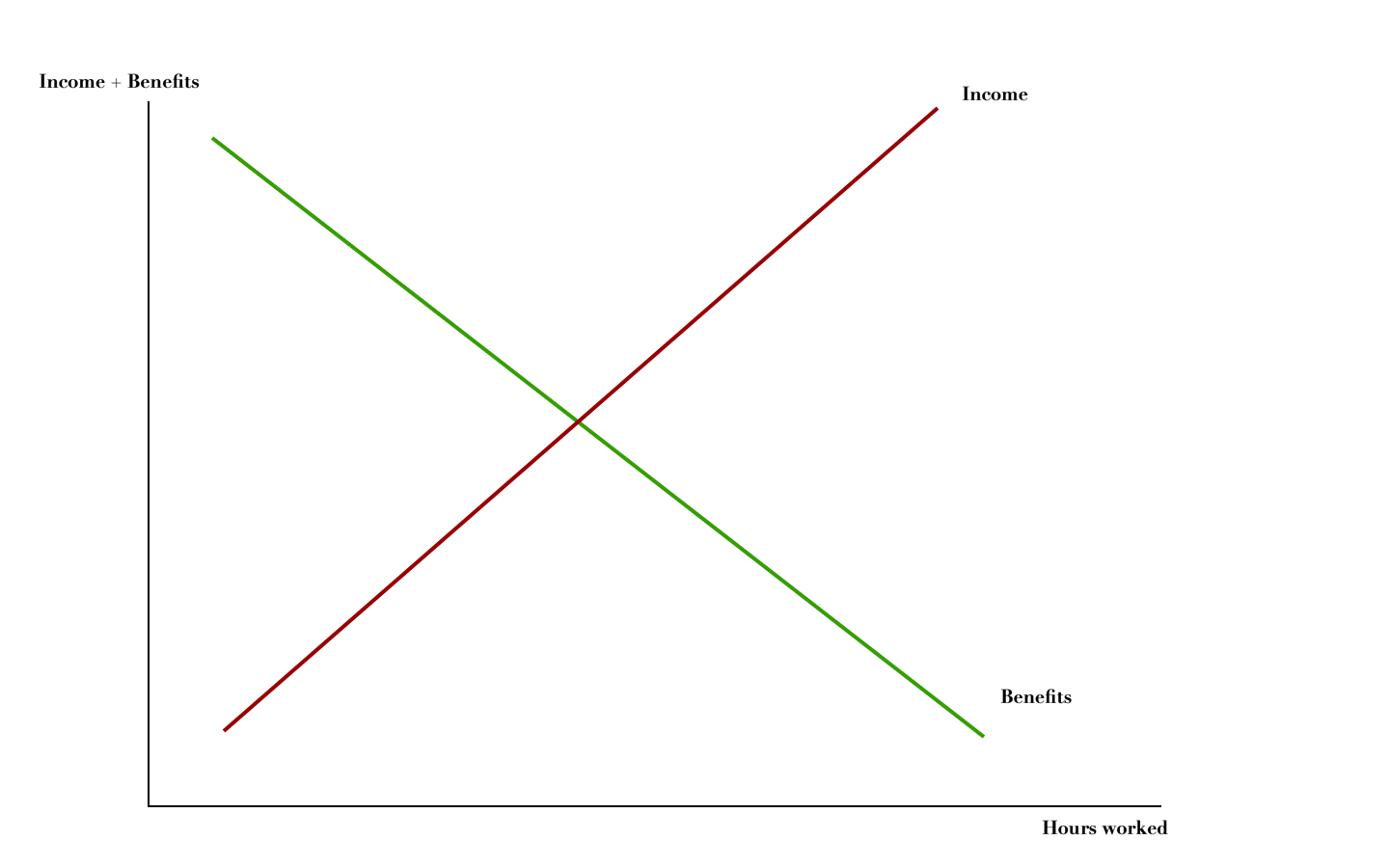

Schematically, the problem is as illustrated in Figure 1. The green line represents the amount of benefits that are available to a family; the more they work, the less benefits they get. The reason for this, of course, is the red line, namely their net-tax income.

At any given point along the “Hours worked” axis, the upper of the two functions represents the sum total of work-based income and benefits. When the “benefits” curve is higher, they dominate total family income, and vice versa.

Figure 1

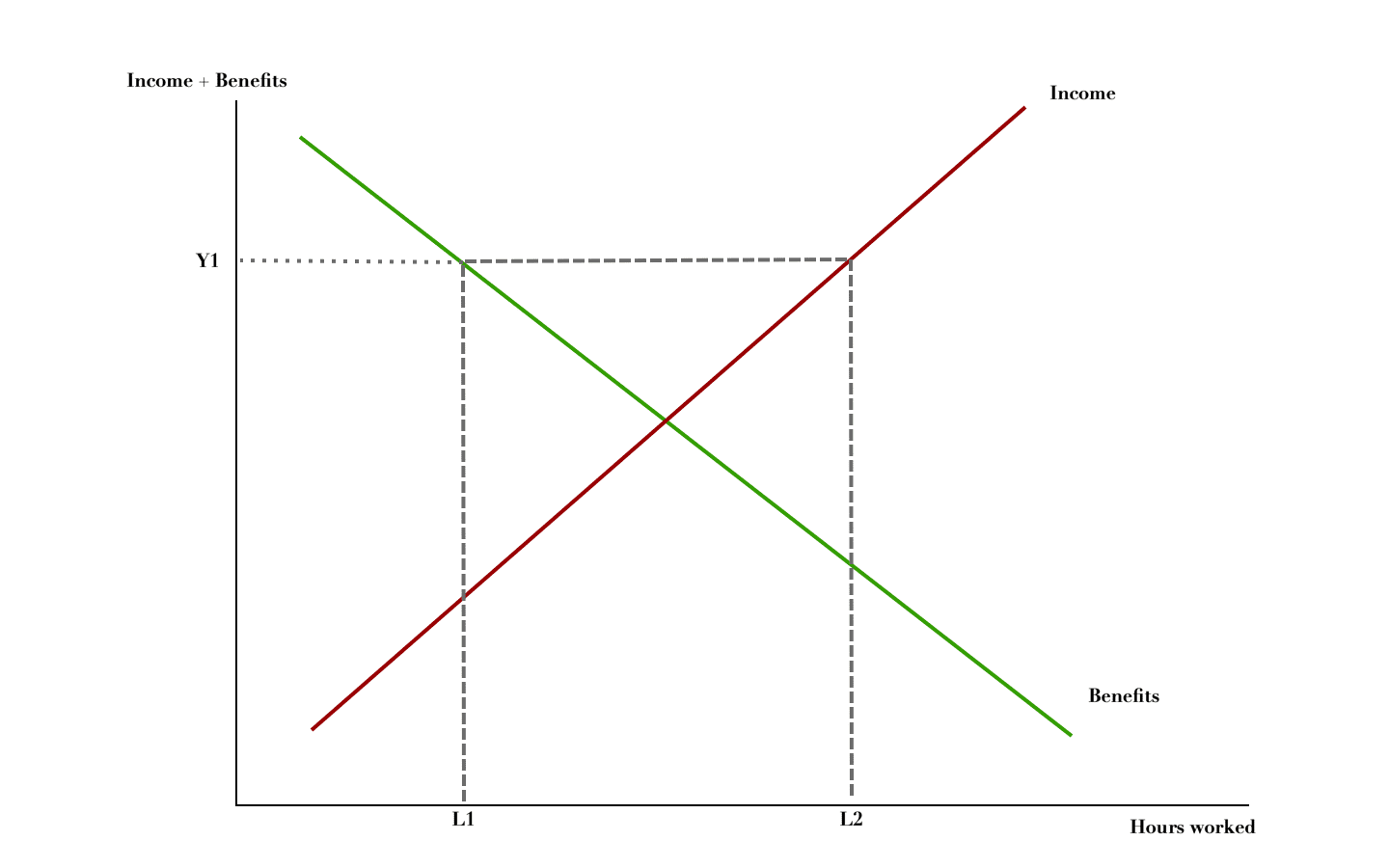

Suppose that a working family wants to reduce their dependence on benefits. Starting at L1 hours worked in Figure 2, they make Y1 total income. As they increase their workforce participation, their income declines because benefits are lost faster than their net-tax income rises. At some point, they have lost so much in benefits that they can enjoy the higher pay from their longer hours worked.

When they get to L2 hours worked, they have fully replaced the benefits lost with work-based income. In total, they now make Y1 again:

Figure 2

So far, we have disregarded taxes. In effect, we have assumed that higher incomes are taxed at the same rate as lower incomes. Since the common way to tax wages and salaries is to impose a progressive income tax—higher rates for higher incomes—it is only fair to factor this into our little schematic illustration of the wage-vs-benefit dilemma. Figure 3 assumes that tax rates rise as household income rises. Technically, this means that the red function slopes upward at a decreasing rate:

Figure 3

In this situation, which is realistic in most European countries, the struggle to get out of benefits-dependency can become increasingly impossible. Realizing this, workers ask themselves to what extent it is worth pursuing careers, accepting promotions, and developing new workforce skills.

The consequences of trapping workers in dependency on tax-paid benefits are bigger and stretch farther than is often recognized. One of the most devastating consequences is long-term economic stagnation: when the workforce is discouraged from improving skills and education, from taking promotions, and from starting businesses (which are taxed under the personal-tax code), overall workforce productivity suffers.

With weaker productivity, businesses cannot afford to pay people more. It is easy to imagine the chain reaction of problems from there: weaker tax revenue, which makes it harder for government to fund its family-benefits program, which in turn forces government to raise taxes to continue to pay for those benefits. Higher taxes add to the barrier to workforce participation—which in turn weakens economic growth.

There is a way to break this vicious circle. I will return to it in a later article.