This year is not going to be good for Germany. From the Deutsche Welle:

Germany’s economy will grow less than expected this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said on Tuesday. It said it expected the German economy to grow by 0.2%, which is 0.3 percentage points less than it estimated in its January outlook.

As I noted recently regarding the ECB’s outlook on inflation, we should be mindful of how economists think about expectations. In this case, what the IMF is really saying is not that the German economy is going to grow more slowly than expected, but that they have revised their expectations regarding Germany’s GDP growth this year.

With that said, the downward revision of the growth outlook is realistic and should be taken seriously by German politicians—especially since this IMF outlook comes on top of a year, 2023, with bad economic performance.

According to Eurostat’s most recent national accounts numbers, Germany is technically already in a recession. After growing by 0.3% per annum in real terms in the first quarter of 2023, German GDP fell by 0.4% in the second quarter, by 0.7% in the third quarter, and by 0.4% again in the fourth quarter.

That is three quarters in a row with shrinking GDP. The standard economic definition of a recession is that real GDP falls year-to-year in two consecutive quarters.

The last time Germany went through a real recession, i.e., not the artificial economic shutdown of 2020, was in 2012-13. Back then, GDP fell by 0.1-1.5% in the second and third quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013. Before that, the Great Recession of 2008-2010 took a major toll on the German economy: from the summer of 2008 to the first quarter of 2010, their GDP fell by 6.3%, adjusted for inflation.

On the surface, the current recession has been mild by comparison. There has been no plunge in overall economic activity, which could be a sign that this is just a ‘breather,’ not a bona fide recession. This impression is reinforced by the growth numbers for private consumption, the largest domestic economic activity: after declining by 0.2% in the first quarter of 2023, 0.75% in the second quarter, and 1.65% in the third, household spending fell by 0.7% in the fourth quarter.

Although the fourth quarter includes Christmas shopping, there is still room to see these numbers as hints of a mild recession.

The problem for Germany is that other variables speak a different language:

There is a similar accelerated decline in imports underway, which tells us that industrial production in Germany is in an accelerating decline. German manufacturers are not only global exporters, but also prolific importers of input products; the factories in Germany are essentially assembly points for parts imported from contracted suppliers abroad.

The fact that business investments have been stagnant for an extended period of time shows that German businesses for some time now have been cautious about planning for the long term. As this caution prevails, production facilities gradually become more obsolete than they otherwise would be; new technology and more efficient methods of production are not implemented to the same degree as they normally would be.

As a result of this, when a recession strikes, there are smaller productivity and profitability margins in German industrial production than there would normally be. The sales reductions that always come with a recession now become a sustainability threat to many businesses that under normal circumstances would have had no such problems.

Right here, we have the real problem with the current recession. Although it looks mild on the surface, it can set in motion a structural change in the German economy where the manufacturing industry does not fully recover. Sweden underwent a similar structural transformation in the 1990s, with the result that the domestic economy permanently lost its ability to support growth and prosperity. Since then, the Swedish economy has survived on what remains of its major exporters, and on cheap household credit.

I am not predicting that Germany will go through a ‘Swedification’ in the coming months and years, but the GDP numbers open for it as a possible scenario. This is bad enough. I have never before seen the German economy being threatened by a structural decline of this kind.

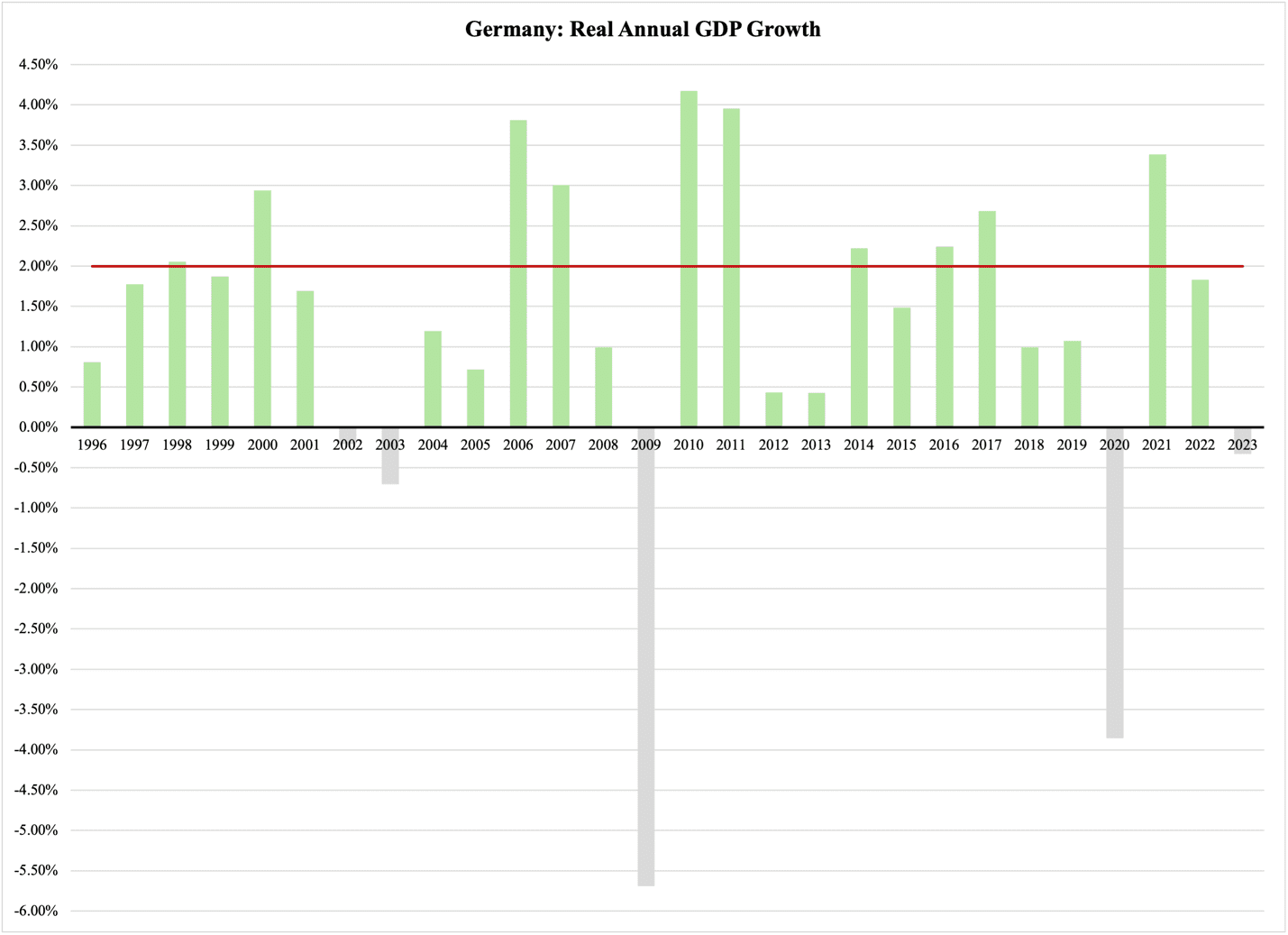

Adding to the worries about a permanent downshift in economic activity is the history of German GDP growth. Figure 1 compares the real annual growth rates (green/gray columns) to the 2% so-called industrial poverty threshold (red line). This is the level of real GDP growth that a country needs to sustain over time in order to produce enough economic resources to advance its standard of living:

Figure 1

In the past four years, 2020-2023, the German economy has only grown by 0.26% per year, on average. Stretching back to 2018, the average growth is twice as high, 0.52% per year. In other words, the German economy is already in a state of glacial decline: its population is slowly becoming poorer.

With this in mind, the outlook from the IMF is a punch in the gut. There is in particular one important consequence for economic policy that we shall return to in just a minute. First, though, a quick reminder of other major macroeconomic variables.

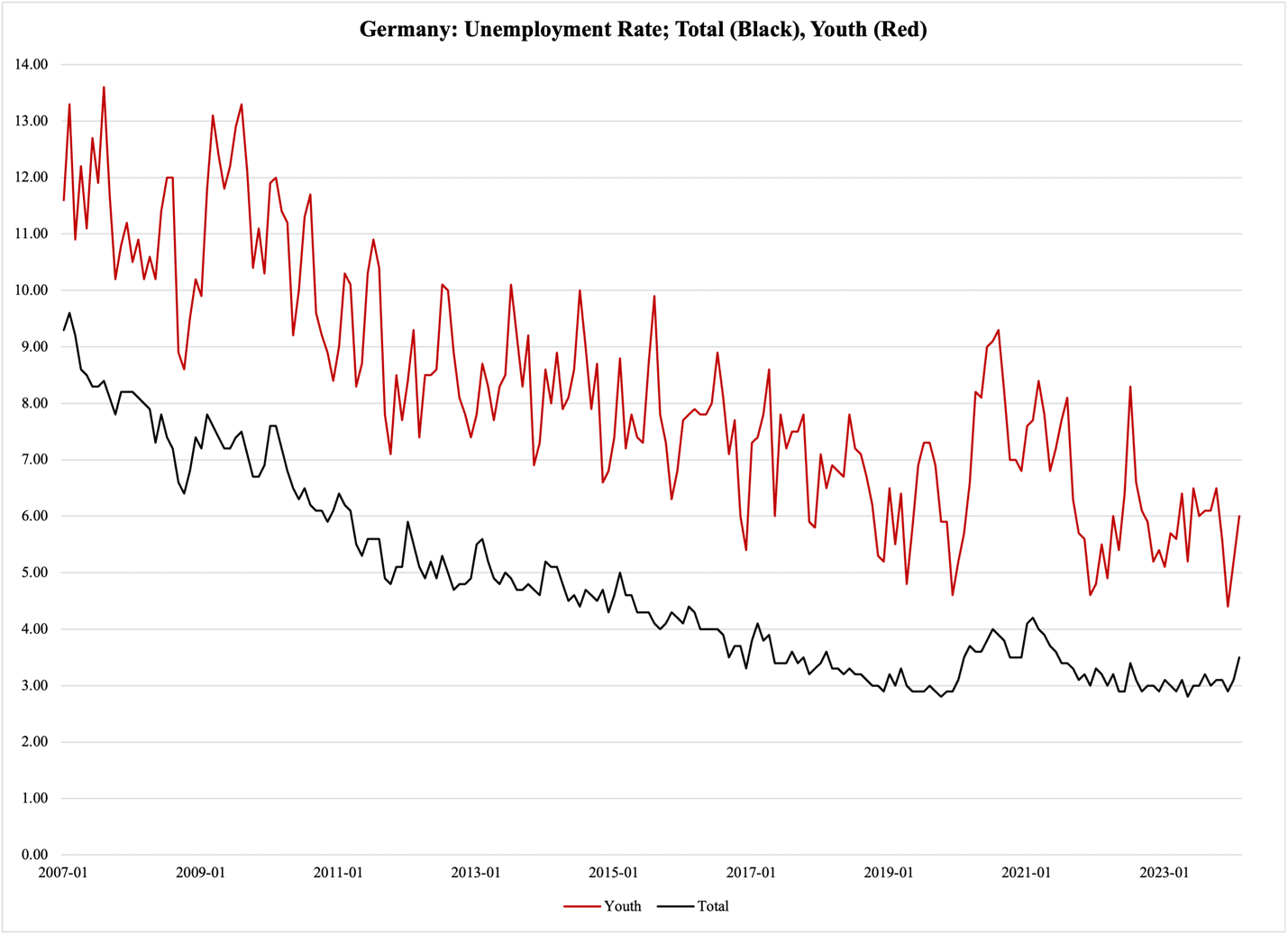

Figure 2 reports unemployment rates, total as well as strictly for young Germans. After a protracted decline over the ten years from 2007 through 2017, the jobless rates have stalled and will not budge any further:

Figure 2

To be fair, it is very difficult for an economy to crawl below 3% unemployment. It can be done, but the marginal costs of filling more jobs at that point are so high that it usually does not make financial sense for the employers. Therefore, for all intents and purposes, it is fair to say that the German economy is operating at full employment.

With that said, please note the uptick at the very end of the black curve. Normally, with a variable that fluctuates short-term as this unemployment rate does, there would be no valuable information in this little ‘kink’ upward. However, it comes at a time—the first two months in 2024—when the GDP numbers combined point to a recession. After having stayed almost perfectly at 3% throughout 2023, there was a sudden uptick in February. At 3.5%, this monthly unemployment rate is the highest since the summer of 2021, when the German economy was returning from the 2020 artificial economic shutdown.

One month’s worth of unemployment rate does not set any trend. Therefore, it is not to be interpreted as a sign in itself of a recession. However, it makes sense if viewed as an anecdotal corroboration of the troubling GDP numbers discussed earlier.

If the recession escalates, one of the many casualties will be Germany’s public finances. When the economy grows slowly, the growth in tax revenue falls behind welfare state spending. As a result, a structural deficit opens in the government’s budget. Germany has such a deficit—it has to a large degree been hidden by a phenomenon known as kalte Progression, or the lack of inflation indexing in the tax code.

The kalte Progression phenomenon cannot protect government budgets when a recession rapidly increases unemployment. The big question for Germany is therefore: what will its government do if the recession turns as ugly as the numbers indicate it could? Will they resort to austerity and exacerbate the recession, or will they defy the EU’s newfound penchant for fiscal responsibility?