In Part I, I explained the structural problem with the U.S. government’s entitlement programs: they are designed to spend money based on

In other words, the cost of these programs is independent of the federal government’s tax revenue. That revenue is determined by factors that are structurally separated from those that determine spending.

The decision on how many people should be eligible for government benefits, and what those benefits should be, is political in nature. Therefore, the only way to stop government spending from outpacing tax revenue is to rewrite the politically motivated foundation for government spending.

This may sound like a purely technical question of little general interest, but as we will see in the entirely new welfare system that I propose here, this political reform is even more revolutionary than the paradigm shift for the American welfare state that President Lyndon Johnson introduced with his ‘war on poverty.’

Today, tax-paid social-benefit programs are designed for the purposes of economic redistribution. People are eligible for help from these programs because their household income is below a certain threshold. This practice is called ‘economic redistribution’ and is by its very nature cost-driving; the very purpose of these programs necessitates continuous growth in their costs.

To see how this economic redistribution works, let us take a look at two of the federal government’s income security programs: the Earned Income Tax Credit, EITC, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP. The former is a cash handout that households with low-to-moderate incomes can qualify for; the latter, formerly known as food stamps, provides grocery benefits to eligible lower-income households.

If the EITC and SNAP programs existed solely to help people get out of poverty, then dependency on these programs would be closely tied to people’s poverty status. This is not the case, though: according to data from the Internal Revenue Service, in 2019, there were 26.7 million tax returns filed by people who were eligible for the EITC. For reasons related to how the EITC eligibility requirements are written, there is almost always more than one person behind an EITC-eligible tax return. We can therefore validly estimate the number of qualifying individuals to be significantly higher than the number of tax returns; to use a rounded number, suppose there are 45 million people entitled to the EITC, either directly as income earners or indirectly as a non-working spouse of an eligible taxpayer.

In that same year, the Census Bureau reported that 34 million Americans were living in poverty. This means that if all individuals who qualified for the EITC in 2019 were also poor, it would have a significant effect on poverty if we took away the EITC. We should see a similar effect if we closed down the SNAP program, which, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, had 35.7 million enrollees in 2019.

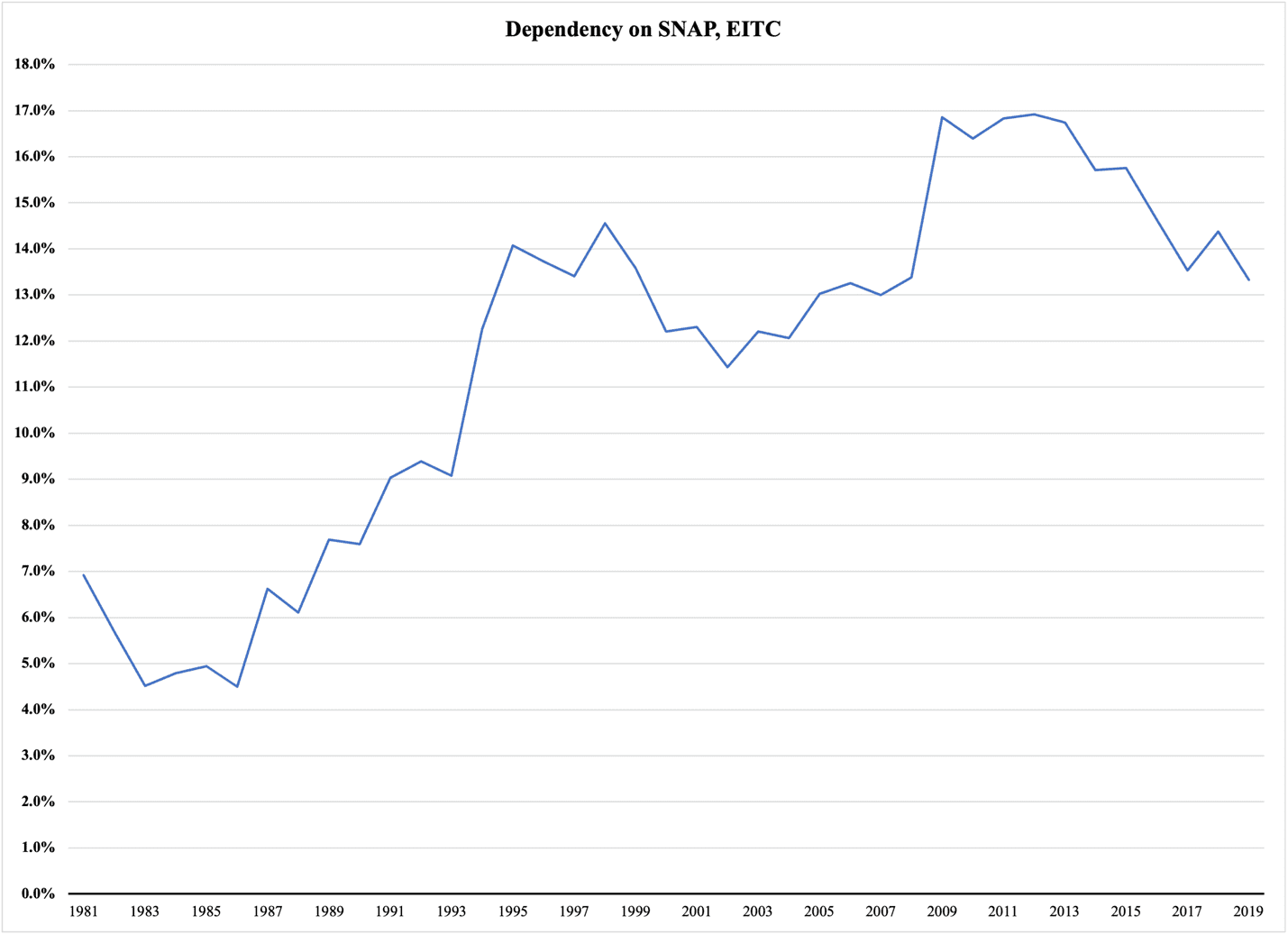

Surprisingly, if we closed down these two programs, it would only have a marginal effect on the poverty rate. Figure 1 reports the share of the population classified as poor, for which the EITC and SNAP determine their poverty status. The vertical axis shows the percentage of the poor whose poverty status depends on these two programs.

Figure 1

At no point since 1981 have the EITC and SNAP programs elevated more than 17% of the poor out of poverty, and yet the number of people enrolled,as recently as 2019, in each of these programs was considerably higher than the number of people who were poor at that time. (This year is used because the U.S. economy was unusually strong that year.)

How is this possible? Here is how: The benefits paid out through EITC and SNAP are very costly without having any significant effect on the poverty status of those who receive them. According to the Office of Management and Budget, these two programs—including related nutritional assistance programs—cost $146.7 billion in 2019. In 2023, they cost taxpayers $220.7 billion; the cost for 2024 is estimated to exceed $234 billion.

The reason why all this money does not reduce poverty is that these programs are not designed to relieve poverty. They are designed to redistribute income. The EITC benefits are tied to household income and fall with rising income. The income threshold for SNAP is tied to the poverty line; for example, in Illinois, a household can get SNAP if their total income is as high as 165% of the official poverty limit.

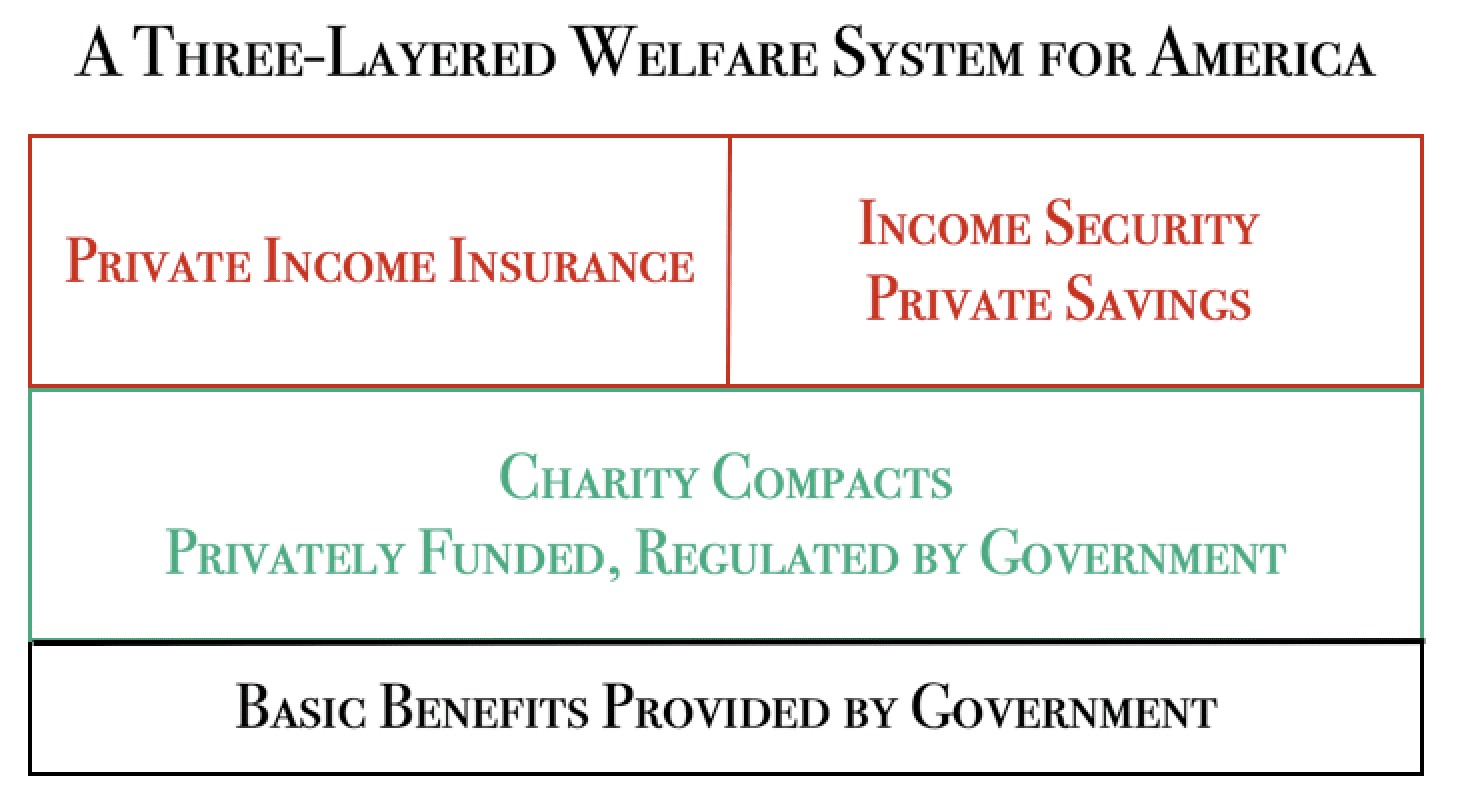

Let us imagine a new welfare system—one that is not designed for income redistribution. Taxpayers are responsible for benefits programs designed strictly for the purposes of poverty relief, but those benefits are only one of three parts—layers—in this new welfare system.

The basic benefits—the ones taxpayers pay for—are available to a person or a household only when all opportunities for self-support have been exhausted. This benefits package provides for the basic needs that eligible individuals have: housing, nutrition, clothing, and health care.

The basic nature of these benefits is crucial; the technical term is ‘subsistence’ but since it has undeservedly gotten a negative connotation over time, it is preferable to simply refer to the standard of the benefits as ‘basic.’ However, regardless of the term, the point is that government shall not provide a standard of living that is in any way competitive with what an able-bodied person can provide for himself and his family by working.

A first reaction to this type of basic benefits program is that it is cruel, immoral, and even stigmatizing. If the reform that replaces today’s welfare state programs with the basic package was the only reform done, i.e., if everything else in the economy remained unchanged, then there would be some merit to such labels. However, the basic benefits idea should not be implemented in isolation; as mentioned, it must be part of a three-layer welfare system where individuals who cannot support themselves are given a pathway back to financial self-determination.

In addition to a system of tax-funded, basic benefits, a new welfare system should provide for the continuation of such programs as SNAP, but in a private form. Instead of the federal and state governments being the funders and operators of this program, private charitable organizations would operate it based on dedicated donations.

This is the second layer of the new welfare system. Its purpose is to provide a safety net that people can rely on before they have to turn to the tax-funded basic benefits. This layer, which we can refer to as a system of charity compacts, relies on taxpayers for support; in order to encourage them to donate to these charities, a new tax deduction would be introduced. It would allow for donations of a certain share of a person’s income tax, for which the donor can make a dollar-for-dollar deduction from his income taxes. (Today’s system only allows a deduction of the tax value of the donated amount.)

This model redirects part of a person’s income tax payments from the government’s general fund to a specific purpose: the charitable provision of food and other benefits to people who cannot fully support themselves. To protect both taxpayers and those seeking benefits from participating charities, the federal government—or the states—would run a certification program. Only certified charities would be eligible to receive dollar-for-dollar donations.

A program like this, which I have previously outlined in detail as a charity-compact reform, would come with several advantages. One of them is that those seeking benefits can choose between providers; if a Christian family prefers to work with a Christian charity, they can avoid those that are run based on other values. If a charity wants to specialize in helping people with addiction problems, it can do so and thereby amass the expertise needed in order to be successful.

Another advantage is that taxpayers can make sure their money is being used according to their values. Donors guided by faith can exercise their beliefs. Someone who does not want work requirements attached to social benefits can donate to an organization that is more generous with their donors’ money than competing charities.

In short, the charity-compact model combines cost efficiency with the productive use of benefits and considerable influence from individuals on how benefits are paid out.

The purpose of the charity-compact model is to add a layer of benefits that people can qualify for, above the basic benefits guaranteed by government. However, for a new welfare system to function fully and with the greatest potential for success, we also need a third layer of reforms: the privatization of income insurance programs for those who are active in the workforce.

Today, it is the duty of government to provide unemployment benefits; if America had a program for paid family leave, that would also be funded by taxes. Instead of having a roster of separate programs and an ad hoc tax treatment of income-security-related employer benefits, a new welfare system would create a market where people active in the workforce can combine savings of pre-tax income—an idea I touched upon in this paper—with the purchase of income-protecting insurance.

When individuals can save pre-tax income, they reduce their current taxable income and defer tax on the saved part until they withdraw the money. A married couple that makes, e.g., $90,000 per year and saves $5,000 per year reduces its taxable income to $85,000. (In this case, they fall into a lower top tax bracket.) If one of them becomes unemployed, he or she can choose between using their unemployment insurance policy or withdrawing pre-tax savings. In the latter case, the deferred tax payments come due upon withdrawal under the tax rate that would apply upon withdrawal.

Figure 2 summarizes the three-layered welfare system. Again, it is important to regard it as a complete model, where each part only makes sense in the full context. It is also important to remember that this system is supposed to replace all the programs under which the federal and state governments currently provide social benefits; the EITC and SNAP were used to illustrate how the current system for income redistribution works.

Figure 2

It can easily be shown that this model would be more fiscally sustainable than the current welfare state; for now, let us note that the only tax-paid part is the lowest layer. Since its benefits are independent of what incomes people had before they sought help, the growth rate of the cost of these benefits will be modest compared to the current program.

Furthermore, it is essential to remember that the two upper layers of this welfare system are meant to shield taxpayers from the burden of providing benefits. They combine this function with giving private citizens pathways back to self-determination—pathways that are tailored to their needs—not a template provided by government.

This is undoubtedly a radical reform model, likely too radical for many to consider at first glance. However, it is essential to remember that this reform is designed to solve a radical problem: the $2+ trillion deficit in the U.S. government’s budget. The programs that this reform targets do not cost the federal government enough to close that gap, but the same principle that is here applied to income security for working-age Americans can easily be adapted for use within health insurance programs. If applied that broadly, the total fiscal effect would be a paradigm changer.