Last week, Donald Trump made a big splash when he said that European NATO members who do not spend at least 2% of their GDP on defense, should not count on support from the United States. They would, he suggested, be left at the peril of foreign aggression.

The former president’s unnecessarily harsh remarks caused both approving echoes in Europe and domestic controversy. One of his most outspoken critics, former Congresswoman Liz Cheney, fired back at Trump in an interview with Jake Tapper on CNN. Cheney explained that the former president

basically made clear that under a Trump administration, the United States is unlikely to keep its NATO commitment, and I think that Republicans who understand the importance of the national security situation, who continue to support [Trump], are similarly going to be held to account.

Cheney also said that Trump’s comments showed “a complete lack of understanding of America’s role in the world.” She also made it sound as if Trump was abandoning America’s NATO allies in general, when in reality the core of the former president’s comment was the inadequate defense funding in some European NATO countries. Cheney ignored the fiscal dimension of the issue, refusing to mention it even as Jake Tapper brought it up.

Despite her ignoring the fiscal aspect of national defense, it is understandable that Cheney responds the way she does to Trump. She does not want to give any impression that there are cracks in NATO’s military capabilities; if, e.g., Russia can see any conditions under which America would not come to the assistance of its European allies, they may exploit those conditions in the hope of gaining an advantage on NATO.

With that being said, Liz Cheney can evade the fiscal dimension of national defense all she wants; it is not going away. Presumably, the 2%-of-GDP defense spending goal exists because, if met by all members, it provides the alliance with adequate military resources. Therefore, when some members do not meet their goal, then, logically, NATO cannot live up to its full military potential.

In 2021, the shortfall in NATO-member defense appropriations amounted to approximately $91 billion. If the American military is supposed to guarantee the full capability of NATO even in the face of funding inadequacies among other members, then Congress would have to add $91 billion to the U.S. defense budget.

If we assume that the funding shortfall is the same in 2024, then, based on estimates from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, Congress needs to take the Department of Defense appropriations from $900 billion to $991 billion. Although NATO members in Europe are in the process of increasing their defense budgets, it remains a fact that, until those increases result in an actual expansion of military resources, Congress will have to increase American defense spending by 11%.

That is $91 billion that will have to come from somewhere. If we remove the unnecessarily provocative parts of Trump’s remarks, this is precisely the point that he was trying to make. There are countries in Europe that do not take defense spending as seriously as we do in America. On the contrary, they appear to prioritize other programs in their government budgets:

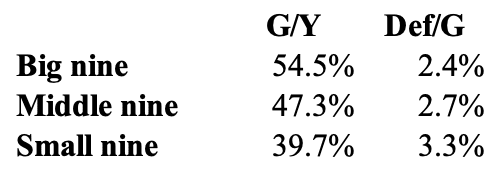

This is not just a rhetorical point. We can see these policy commitments in the numbers for government spending. See Table 1 below, which reports two things:

The table reports these numbers for the 27 members of the European Union. The EU does not perfectly overlap with NATO, but with Sweden on its way into the defense alliance, the difference is negligible. Although there is a small number of NATO members that are not in the EU, the overlap is compelling enough to make a NATO-relevant point about policy priorities.

Looking at the first column, we have nine EU member states—the “Big nine”—where government spending on average was 54.5% in 2021. That same year, these nine countries on average spent 2.4% of their total government budgets on their national defense:

Table 1

In the group with “small” governments—where governments in 2021 spent an average of 39.7% of GDP—we find the largest share of government budgets going to national defense.

Before we continue, it is important to note that these numbers are not testing the 2% of GDP defense spending commitment. The reason is simple: our purpose here is to analyze policy priorities, not NATO spending compliance per se.

Furthermore, the raw data they are based on are in national currencies and current prices. The often-cited NATO numbers on defense appropriations are typically in U.S. dollars and adjusted for inflation; the NATO database using current-price data is too limited for our purpose here.

By using national currencies and current prices, we get closer to the actual policy decisions made by the legislatures in the member states; when lawmakers in, e.g., Denmark pass a government budget, they do so based on Danish kronor, not U.S. dollars. By converting their appropriations to dollars, we put some statistical distance between us and the policy priorities that the Danish parliament makes.

In other words, what we see in Table 1 is a picture, as genuine as possible, of what the governments in Europe prefer to do with their tax revenue. The countries that have the biggest governments are more inclined to spend their money on non-defense programs; those who keep their government limited appear to take defense appropriations relatively more seriously.

But if ‘big government’ countries are not that concerned about defense spending, what do they use their tax revenue for?

The answer is simple: the welfare state. Narrowly defined, this structure of ideologically driven government programs consists of spending on health care, education, social protection, and community and housing programs. (There is a broader definition, but since it is a bit controversial, we use the narrower definition here.) When we examine the consolidated government outlays of the 27 EU member states, we find something quite interesting:

Of the 14 big-welfare-state countries, 12 are NATO members; Austria is not a member and Sweden has a pending membership.

The budget priorities among European NATO members raise two questions, one of which we have already asked:

How do the proponents of a blank-check American commitment to NATO intend to fund that check? Let us keep in mind that borrowed money—the budget deficit—is the single largest revenue source for the federal government.

Now for the second question. The fact that the top-14 welfare states in Europe give heavy priority to economic redistribution and only pay marginal attention to their defense budgets means that a U.S. blank check to NATO funding is the same as a U.S. taxpayer subsidy to the socialist welfare states in these countries.

Are conservative members of U.S. Congress comfortable with subsidizing Europe’s economic redistribution, socialized health care, and programs that discourage economic growth and traditional families?