As I noted last week, the outlook for the European economy is not very good. This is especially the case for the 20 EU member states who share a common currency.

What about the EU states that still have not adopted the euro? Do they generally fare better than euro countries, or should they rush to join the currency area?

Currently, there are seven EU members who maintain their own currencies: Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden. Every country is different, of course, but as I have explained in separate articles, it is almost impossible to find any merits to a country joining the euro zone. Back in June I explained why Hungary should stay out of the euro; a month later, in a two-part analysis, I reached the same conclusion regarding Sweden.

A year and a half ago, I issued some stern advice for the Croatian government, as they were preparing for their January 1, 2023 entry into the currency area. Time will tell if I was right on the money there, but we can already say that there are two points that all prospective euro-zone members ought to consider carefully:

1. No more exports-led GDP growth. Both Sweden and Hungary have been able to take advantage of being outside of the euro zone by letting their currencies weaken vs. the euro. Their export-promoting policies have been largely negative for Sweden but unquestionably positive for Hungary.

2.Increased risk for fiscal crises. A decade ago, Greece was subjected to economically destructive austerity measures. One of the alleged reasons for the EU to impose these measures was that it needed to prevent Greece from seceding from the euro; with the effects for the Greek economy being downright catastrophic, one has to ask to what extent it is ‘worth it’ to join the currency union and risk being subjected to similar measures in the future.

Aside from these arguments, we can glean some interesting information from a broader look at the macroeconomic performance of economies inside vs. outside of the euro zone. Let us see what happens when countries join the euro; we use the ‘evolving’ definition of the area, i.e., the configuration it has in each year of comparison. This allows us to see what difference it makes as the euro zone expands, but it also allows us to compare the euro zone to those seven EU member states that to date have not joined the currency area.

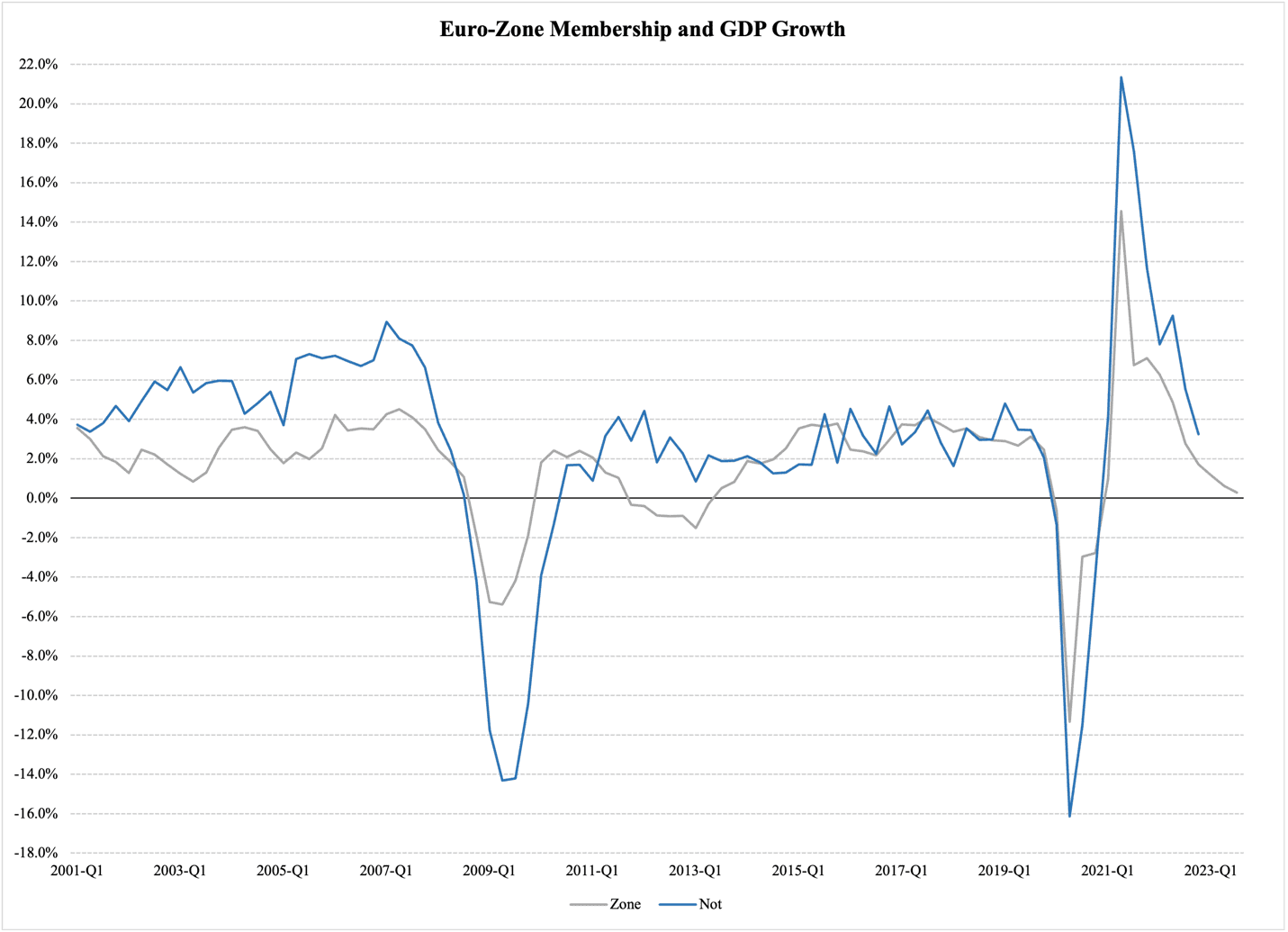

Figure 1a compares GDP growth in the 20 current euro zone members. The member states are split into two groups: those who are members of the euro zone at any given point in time, and those who are outside the group.

An interesting pattern emerges: early on, when the euro zone has 12 members or less (prior to 2008), on average the non-members (blue) have a higher average growth rate than the members do (gray). Then, as membership gradually grows, the visible difference between euro and not-yet-euro states fades away:

Figure 1a

The last of the current 20 members to join the currency area was Croatia, which has now been a member for one year. It is too early to evaluate their particular experience, but the general message in Figure 1a is that as the current euro zone membership list has grown, those who have joined have lost out in terms of lower GDP growth.

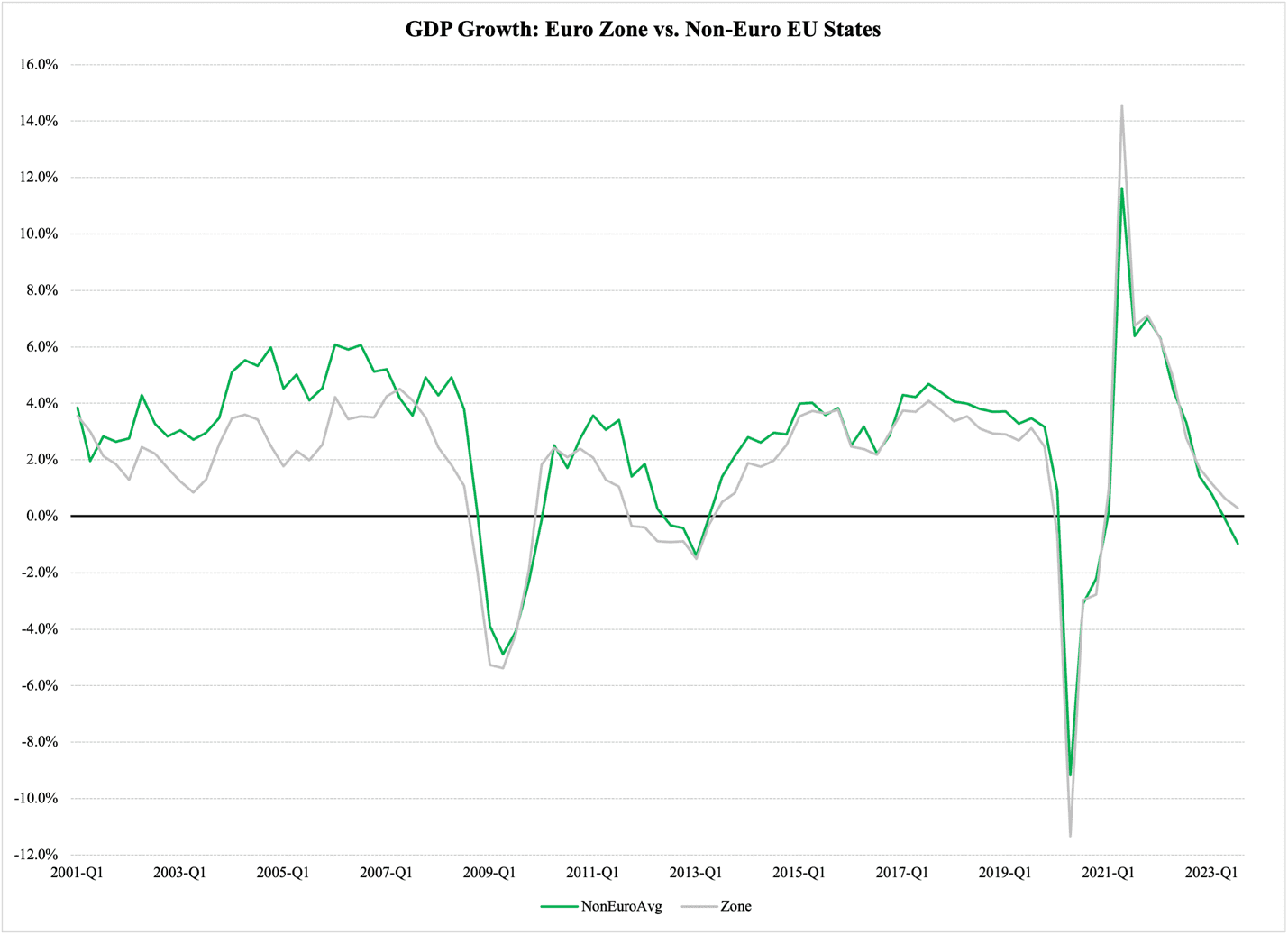

We get a similar message if we compare the euro zone to the seven EU states that still maintain their own currencies. Their average, inflation-adjusted GDP growth is reported in Figure 1b (green), where it is compared to the same evolving euro zone (gray) as in Figure 1a:

Figure 1b

But does it really matter if one economy grows a little bit faster than another? Is not the GDP measurement for economic progress really overstated?

These are big—and undoubtedly valid—questions; briefly, the answer is ‘yes.’ It does matter if the economy is stagnant or growing. With an expanding economy, there are more opportunities for all of us to pursue careers, reap the benefits of higher education, start businesses, and make productive investments. Higher economic growth affords governments more resources to improve what they are responsible for, which in most European countries means the entire health-care system.

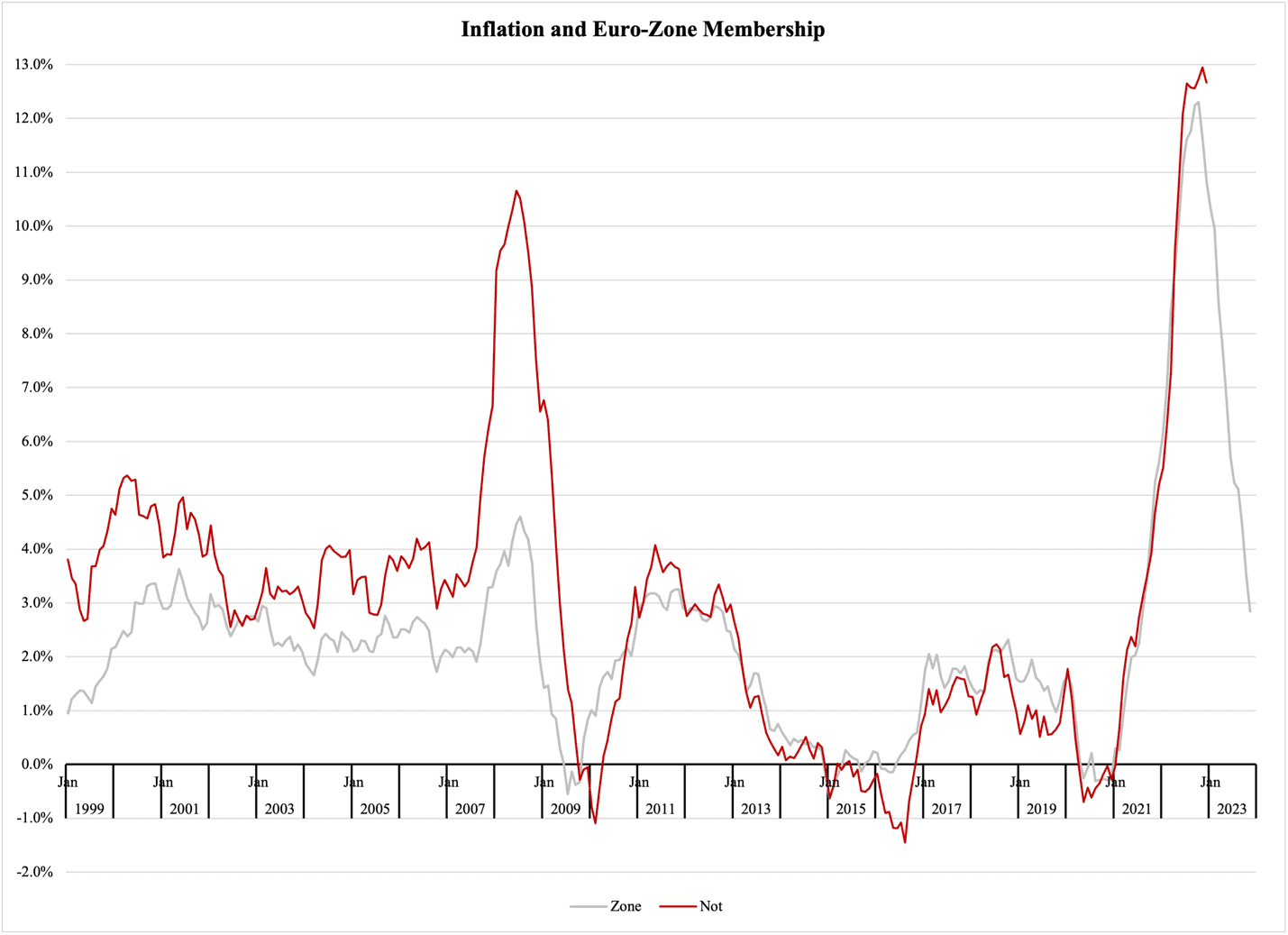

In addition to GDP growth, we can also gain some useful insights into the (non-existing) benefits of the euro zone by comparing inflation rates. Things are a bit more complicated here, though, compared to the GDP numbers we just analyzed: unlike economic growth, inflation is a highly volatile variable. As this example shows, that volatility makes it difficult to calculate meaningful averages:

The average inflation rate for these two countries is 77.7%—a number that tells us absolutely nothing about their economies.

Repeating the comparison from Figure 1a—let us simply call it Figure 2—gives us a somewhat more accurate image of what happens to inflation when a country joins the euro zone. Using the same evolving concept of the currency area as in Figure 1a, we get the interesting result that inflation was higher in current euro-zone member states, until they adopted the common currency:

Figure 2

But wait—have we not just found a good reason for a country to join the euro zone? If it means lower inflation, isn’t that good for the economy over time?

All other things equal, the answer is obviously ‘yes’. However, the problem here is not that inflation was a little bit higher in euro-zone countries before they joined it. The problem here is that inflation is lower in the euro zone.

Put differently: the difference in inflation rates overlaps with the difference in GDP growth. In this particular comparison, countries that tend to have higher inflation also tend to have a higher rate of GDP growth. This tells us that the extra inflation they experience compared to euro-zone members, is the result of strong growth and high demand for all kinds of resources in the economy.

This type of inflation, commonly referred to as demand-pull inflation, almost never poses a serious threat to the economy. It weakens and goes away when the economy hits a recession. Therefore, it is fair to say that if a country can enjoy a strongly growing, sprawling economy rife with opportunities for everyone to better their lives, and if the price is a modestly higher inflation rate than otherwise, then the latter is a price worth paying for the former. That does not mean that countries outside of the euro zone have to accept higher inflation; it all depends on their individual policy choices where they end up in terms of price stability. However, it is essential to keep in mind that countries within the euro zone have much fewer opportunities to pursue their own economic policies than those who remain outside of it.