The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released the latest inflation numbers this week, and the media went on a frenzy. From the USA Today:

After tumbling in the fall, inflation edged up in December, underscoring that it’s too soon to sound an all-clear signal after the biggest spike in consumer prices in four decades.

The newspaper also quotes Jason Schenker, an economist with the consulting firm Prestige Economics, saying that the December inflation figure “was disappointing for those looking for a continued easing” of price hikes.

The Washington Times was more pointed in its comments:

Inflation accelerated in December … complicating President Biden’s reelection argument that he has made progress on trimming rising prices. … The increases were much higher than forecasted by Wall Street analysts

Along the same lines, Fox Business opined:

Inflation rose more than expected in December thanks to a jump in energy and housing costs, underscoring the challenge of taming price pressures within the economy. … Prices climbed 3.4% from the same time last year, coming in above both the expectation from Refinitiv economists and the 3.1% gain recorded in November.

Over at CNN, the story leaned in the opposite direction. Reporter Elisabeth Buchwald turned attention away from the Consumer Price Index, CPI, number. Instead, she tried to highlight the Personal Consumption Expenditure, PCE, method. Buchwald claims that the Federal Reserve, in making its monetary policy decisions, prefers the PCE over the CPI.

There is no need to dramatize the new inflation numbers, and there is certainly no reason to claim that the lower inflation rate produced by the PCE method is somehow better than the CPI method. As we will see in a moment, aside from different data collection methods, the only practical difference between the two is that one is more volatile than the other.

Let us get back to that in a moment. First, the facts.

As reported in the media, the CPI-based inflation rate for the U.S. economy in December was 3.4%. However, for the sake of nuance, it is worth noting that the rate was 3.35%. When Fox Business compares December to November, they report the latter month’s inflation rate at 3.1%, which to be exact was 3.14%. In other words, what looks like a 0.3 percentage-point leap in inflation was in reality a 0.21-point increase.

It may seem nit-picky to argue over decimals and minor differences like this, but when it comes to inflation rates, it matters a great deal. When we report inflation as 3.4%, it can be anywhere from 3.35% to 3.44%; likewise, 3.1% can represent any number from 3.05% to 3.14%. The difference between the two outliers here is almost 0.4 percentage points, while the narrowest gap is about half as big.

These nuances matter a great deal to any inflation forecast: if inflation jumps by 0.4 percentage points in one month, it could signal a rebound of a more lasting character; by contrast, a 0.2 percentage point increase is most likely just a bump in the road to lower inflation rates.

Since most of the media has compared November and December the way Fox Business does, giving the impression of a 0.3 percentage point increase in the annual inflation rate, the implicit forecasting message in their reporting is not too dramatic. However, since the actual increase is smaller than that, it is reasonable to assume that we are not looking at any kind of reigniting of inflation. More likely than not, this is a temporary upward ratchet in a slow-motion move back toward 2% annual inflation.

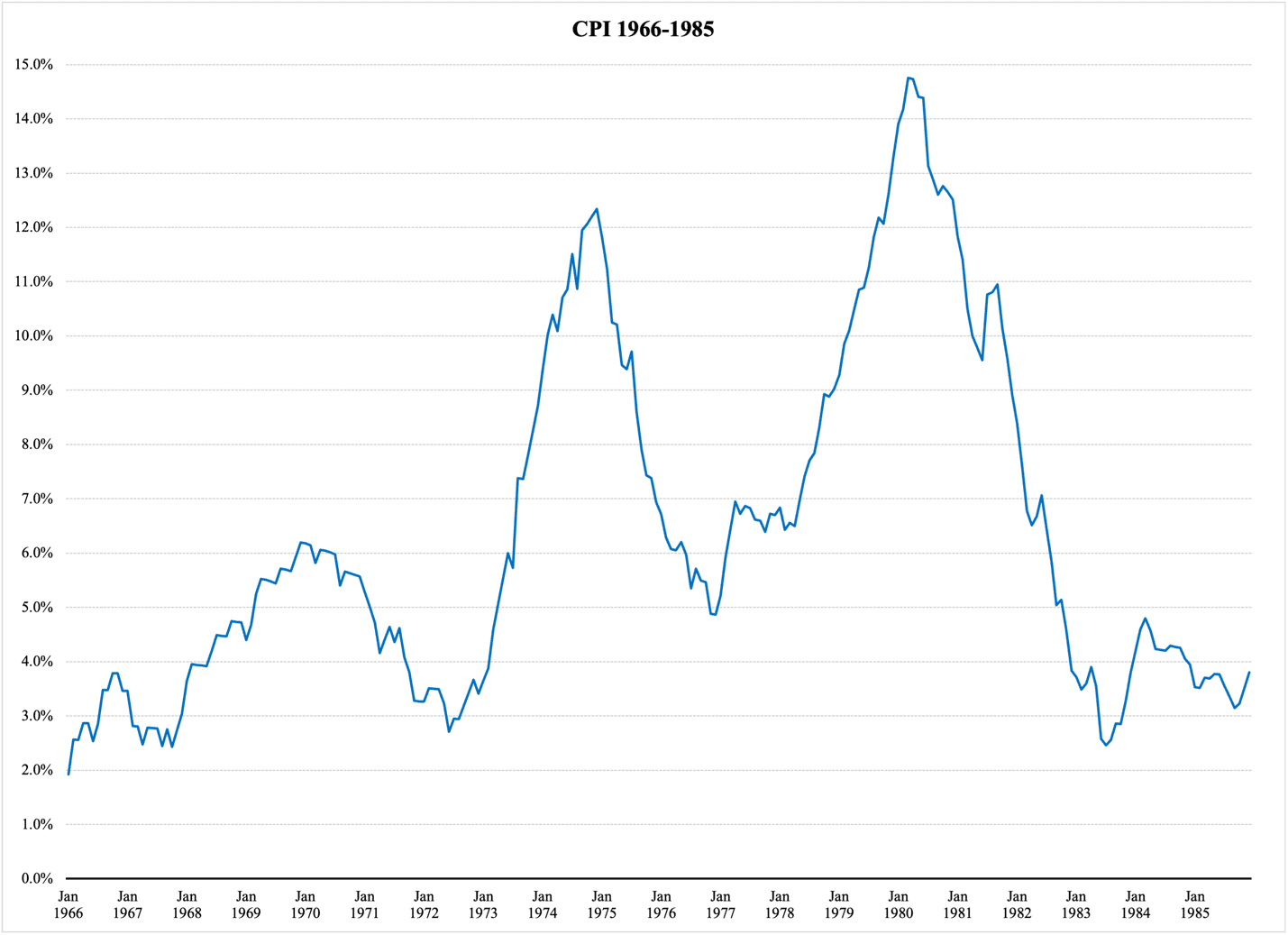

These ratchets are not uncommon, especially in a high-inflation economy. Figure 1 reports the CPI-based inflation rate for the U.S. economy in 1966-1985. After inflation topped out just above 14.7% in 1979, it fell almost uninterruptedly through 1980 and the first half of 1981. However, after reaching 9.55% in June inflation rebounded to 11% in September. After that, the decline continued:

Figure 1

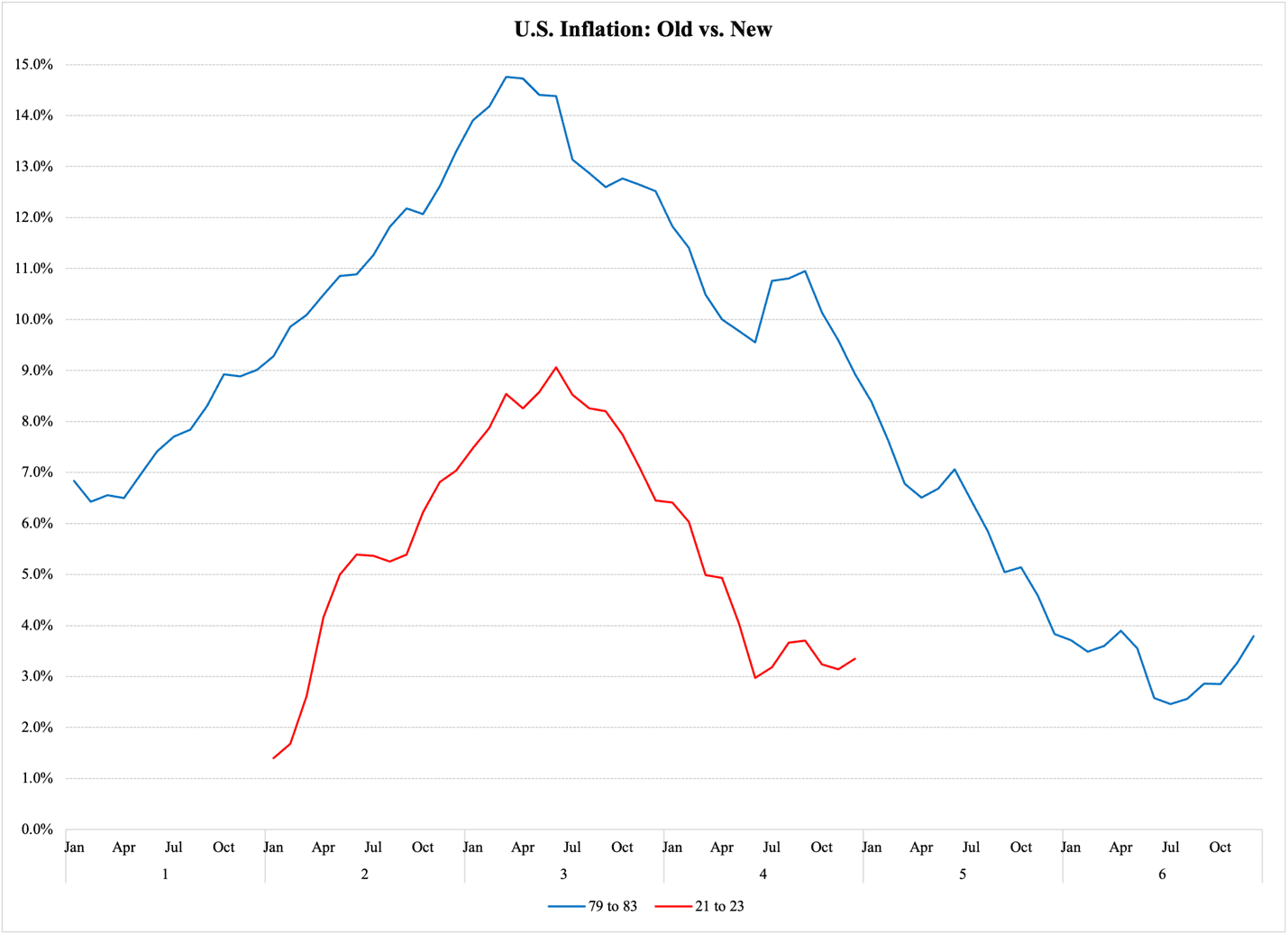

It is also worth noting the rise in inflation that took place in 1984. It is not unlike the inflation pattern we are currently dealing with; Figure 2 compares the last of the inflation peaks in Figure 1 with the most recent CPI trend. The older inflation episode (blue) stretches over six years, 1979-1984; the most recent one (red) covers three years, 2021 through November 2023:

Figure 2

Compared to the experience of the early 1980s, our current return to lower inflation has been smooth and relatively quick. Given this, the upward ratchet in inflation in December is nothing dramatic. Just like inflation in the 1980s continued to fall after the period covered in Figure 2, inflation will decline in 2024.

But what about the Personal Consumption Expenditure method for measuring inflation? Does Elizabeth Buchwald over at CNN have a point in suggesting that it is a better method than the one based on CPI?

No, she does not. The PCE method is more comprehensive in that it is based on all consumer spending, but for this reason, it is also produced more slowly. This is why we have a CPI number for December, but no PCE number.

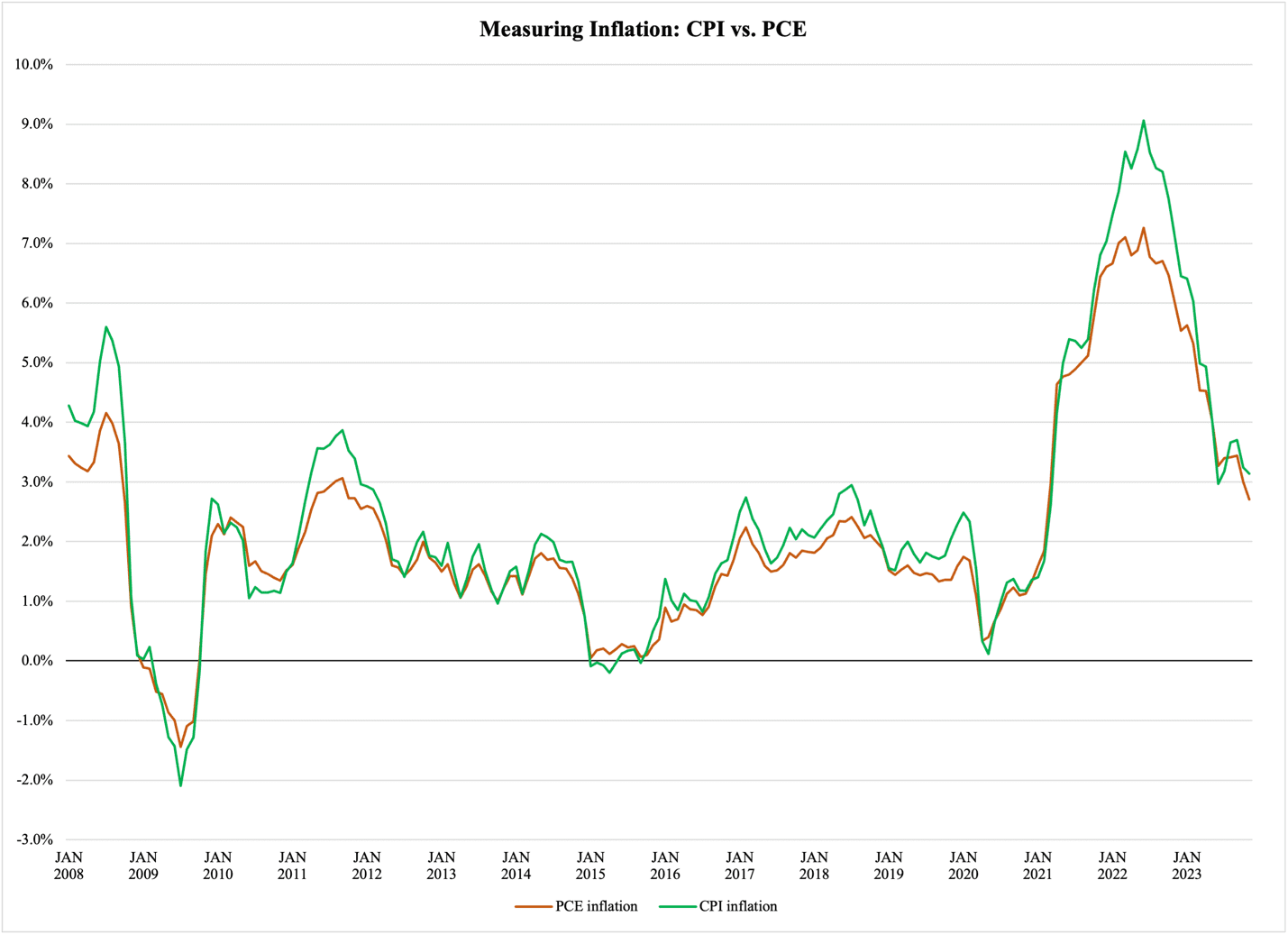

Furthermore, the only difference in terms of the inflation rate is that the PCE exhibits less volatility than the CPI does. The inflation trend is the same in both methods. Figure 3 compares the two, showing that they ‘take turns’ being higher and lower. The CPI rate is higher in, e.g., 2008, 2011, and 2017-2018, but lower than the PCE inflation in 2009-2010, 2015, and 2020, just before the surge in inflation begins:

Figure 3

As recently as in June and July, CPI inflation was lower than its PCE counterpart. Since CNN’s reporter preferred the PCE measurement for November, thus being able to report a lower inflation rate than the CPI-based reports had, presumably, this means that she relied on CPI numbers when she was reporting about inflation back in the summer.

Inflation is on its way down in the United States. This means that the Federal Reserve will cut its policy-setting interest rate. The earliest point in time this will happen is March, but more likely it will happen in April; May would be a bit late.