Much like the rest of Europe, Sweden is heading into a recession. Given its history of ill-fated fiscal policy adventures, we have reasons to worry that the incumbent government will make a bad macroeconomic experience worse.

A year ago, I wrote an economic obituary over the Swedish economy:

Three decades of debilitating fiscal policies, purposely designed to inflate one of the world’s largest and most unsustainable welfare states, are about to boomerang right back at those who created those policies. This new crisis could very well overshadow the one from the early 1990s.

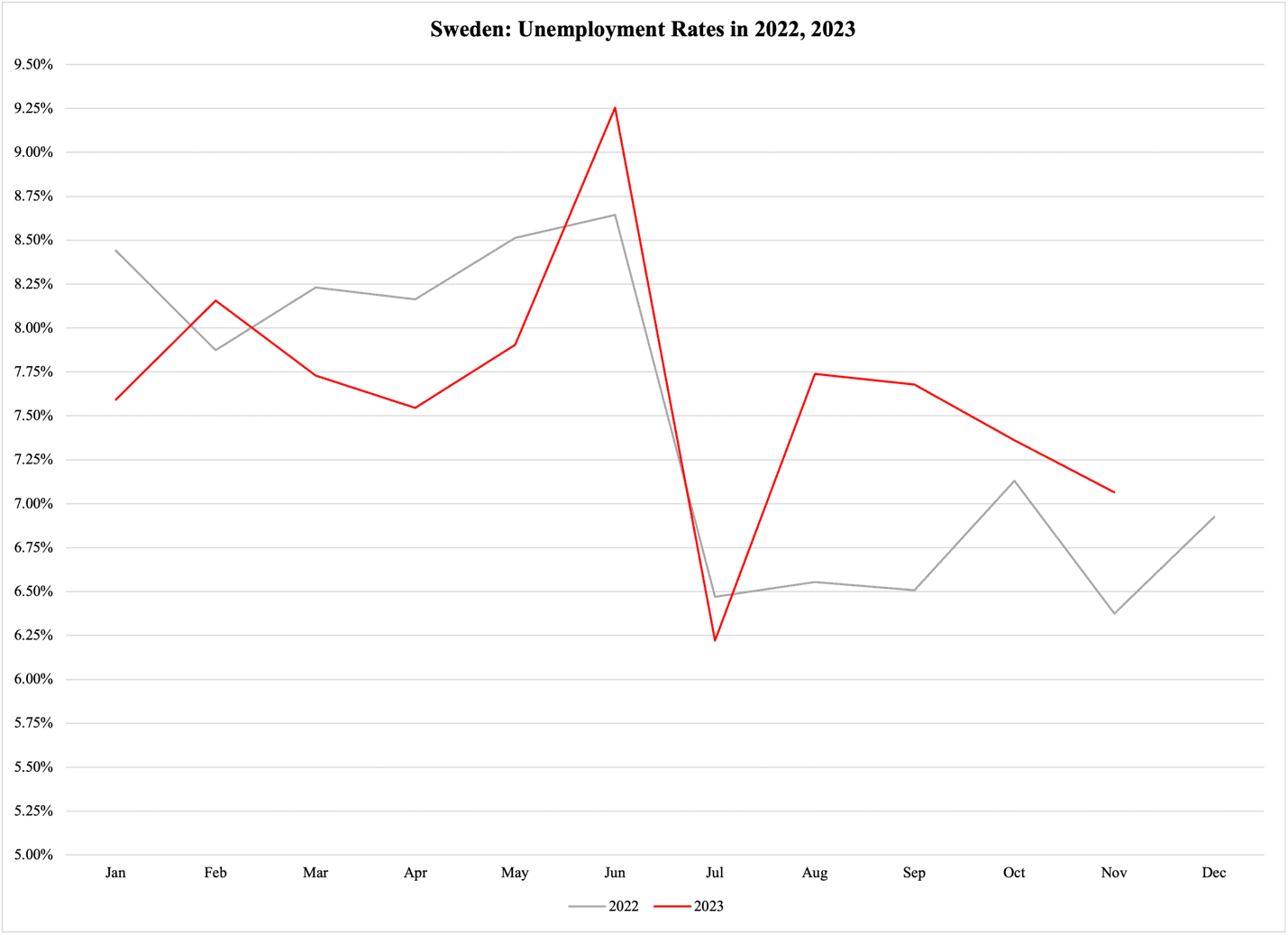

That new crisis is now on its way. The latest workforce numbers from Statistics Sweden show a flattening of the number of Swedes who have a job, and a troubling rise in unemployment. Figure 1 compares the jobless rates for 2022 (gray) and 2023 (red); while 2023 started out lower than 2022, the last three months do not look good at all:

Figure 1

The rise in unemployment is now followed by bad news on the tax front. Statistics Sweden again:

The total local income tax rate increases on average next year … Looking at the country as a whole, the tax increase is the largest in nine years.

The local income taxes in Sweden consist of two parts (hence the “total” comment above):

Going into 2024, Swedes will pay 32.4% of their taxable income in local income taxes. This is 0.5 percentage points higher than what it was in 2014; much of the increase over the past ten years took place before 2021.

The new increases in local income taxes are not drastic by any measure. With an average increase of 0.13 percentage points, this upward drift in the tax rates will not have any significant negative economic consequences. However, that does not mean that they will pass unnoticed: this is still a tax increase all the same. It is important to remember that for low-income earners, every fraction of a dollar, euro, or krona matters, especially when it comes to a tax hike that erodes their purchasing power.

The biggest problem with the uptick in local income taxes is that they can easily become part of a pattern of rising taxes. To date, there are no indications that Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson and his center-right coalition are planning any tax hikes. On the contrary, all other things equal, I would expect Kristersson to hold firm against higher taxes.

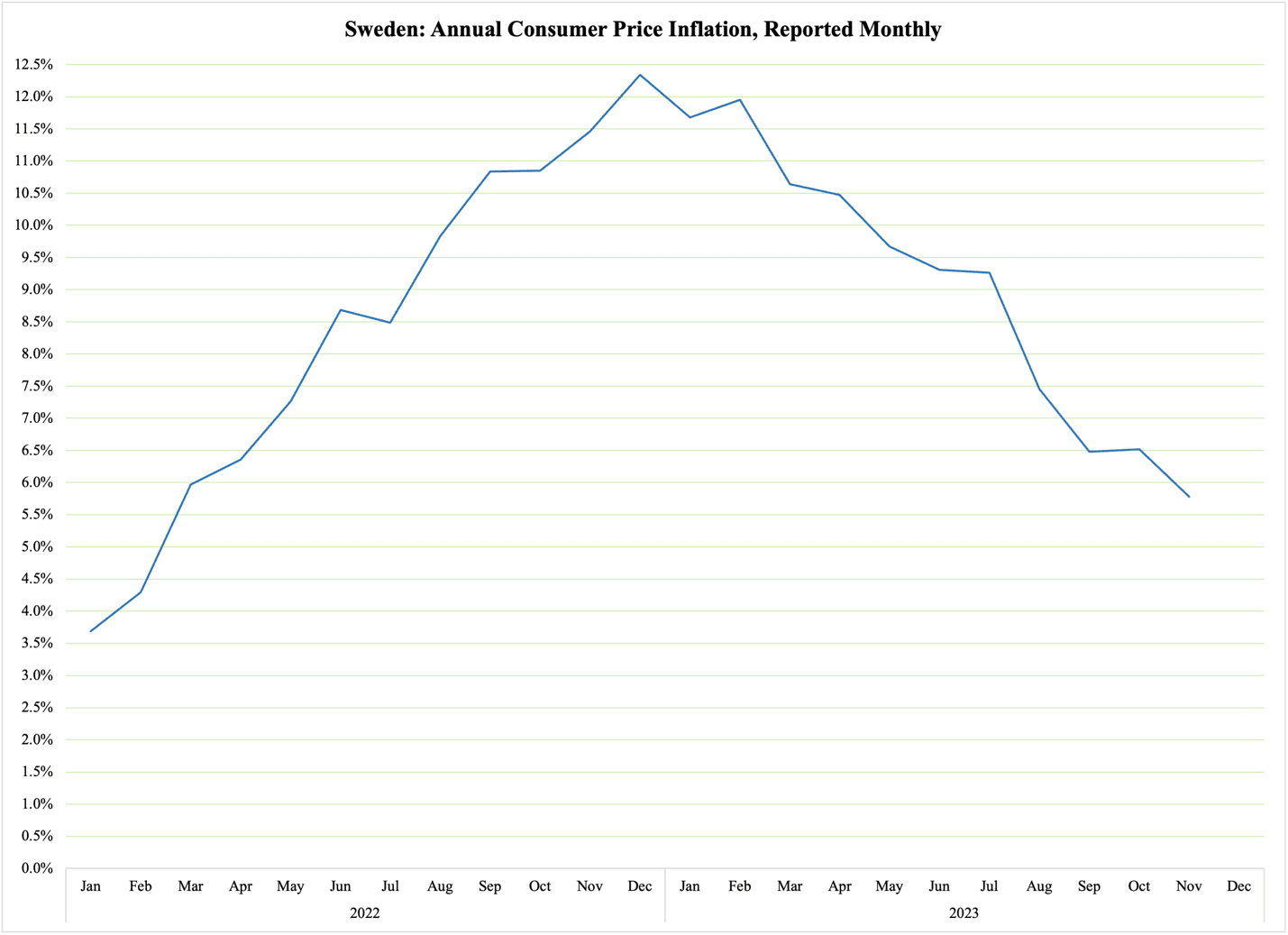

However, the Swedish government has a history of using tax hikes to fill holes in its budget, even when the economy is in a recession. The risks associated with such austerity-driven policy measures are considerably higher today, when Sweden still has to deal with an elevated inflation rate:

Figure 2

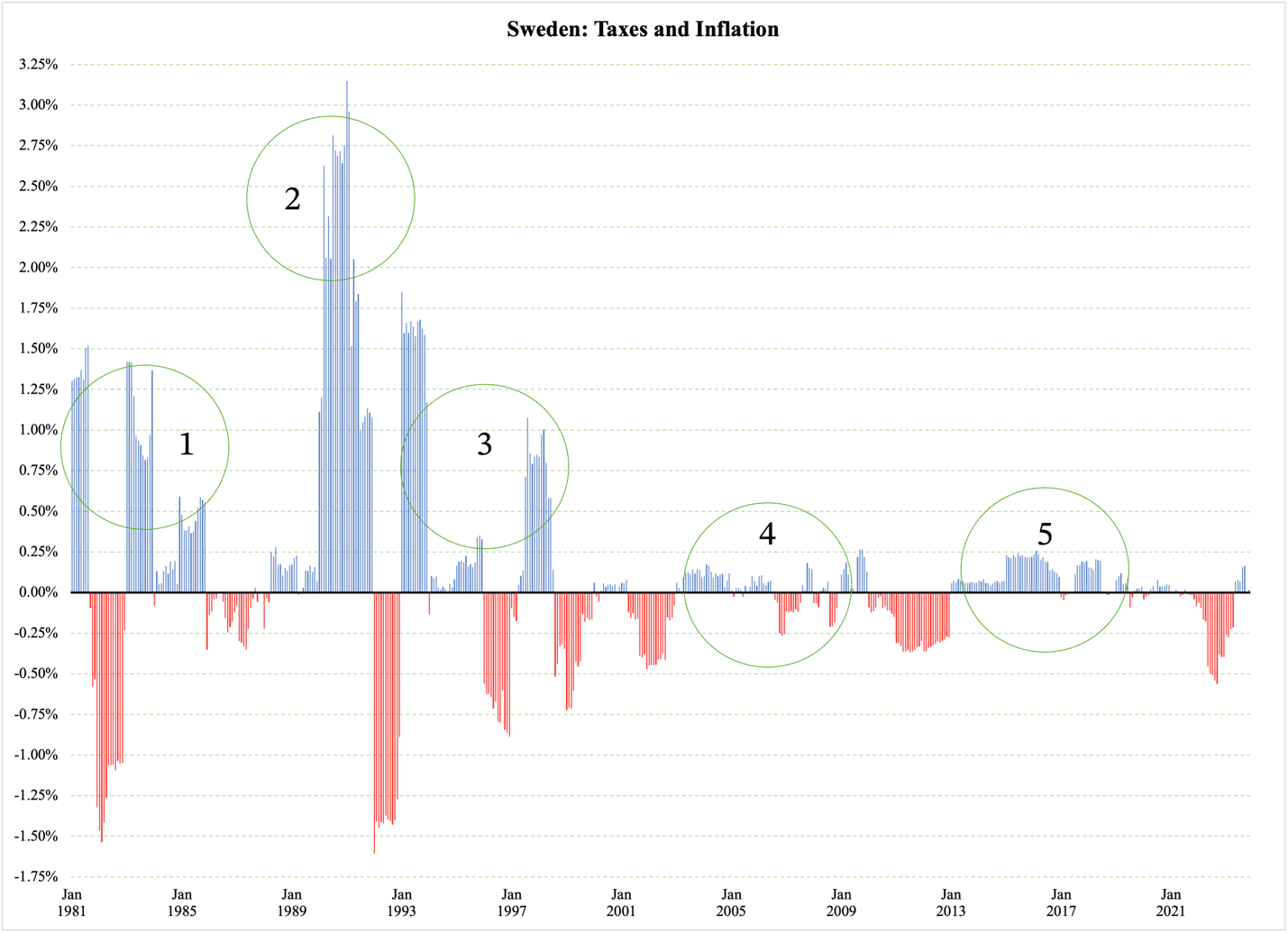

Figure 3 reports how taxes have influenced consumer-price inflation in the past. Blue bars report the additional inflation that is attributable to taxes; correspondingly, red bars report the reduction in inflation thanks to lower taxes.

Of the five episodes marked in Figure 3, three are of special interest here:

Figure 3

In episodes 1, 3, and 5, the Swedish government raised taxes in order to balance its budget. These tax increases consistently translated into higher inflation; in the first two cases—the stagflation era of the early 1980s and the austerity period in the 1990s—higher taxes raised inflation by a full percentage point or more.

A one-percentage point higher inflation may not seem to be that much, but think of it this way:

This is precisely what happened during episode 2 in Figure 3. An exquisitely unintelligent tax reform almost doubled the base for the VAT, or value added tax. The inflation effect was a temporary but economically painful spike in inflation; tax hikes accounted for more than one-quarter of inflation in 1990 and for one-fifth of inflation in 1991.

It is important to keep in mind that not all inflationary effects of taxes are the results of deliberate fiscal policy. Episode 4 in Figure 3 shows a cyclical pattern where taxes occasionally add a small margin to the increases in consumer prices, and occasionally subtract from consumer-price inflation. This episode, which coincides with a center-right coalition under Prime Minister Reinfeldt taking over from a social-democrat government in 2006, is ‘normal’ in the sense that it is largely free of political intervention in pursuit of a balanced budget.

The non-policy driven fluctuations in tax-driven inflation are not unique to Sweden. They exist in every economy with a complex, ‘modern’ tax system, especially those that put strong emphasis on taxing consumer spending through a VAT and excise taxes with similarly inflationary effects.

Again, there are no signs that Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson will go on a tax-hiking spree. At the same time, Kristersson has yet to face the ferocity of a budget crisis in a turbulent recession. When he gets there, it remains to be seen if the prime minister can avoid repeating the catastrophic mistakes of the 1990s austerity measures, which I analyzed in detail in chapter 5 of Industrial Poverty (c.f. pp 173-179).