Europe has a problem with its economy. Most of the EU states are slowly sinking into a recession, and their taxpayers can’t fund the big welfare states that their governments have promised their voters.

The result is a stagnant GDP and widespread budget deficits; as the recession sets down roots in the economy, the deficits are going to get bigger and costlier—at a time when most EU states already have dangerously high debts. As more debt is created, Europe inches closer to another debt crisis; most EU member states are playing with fiscal fire. The economic crisis in 2008-2010 showed with chilling clarity what economic disaster awaits once the investors in government debt lose confidence in a government.

Europe is on its way back there, and the political leadership in Brussels as well as in the member states need to take urgent action to show that they are not going to allow another round of destructive, runaway budget deficits.

Last time around, the meltdown of investor confidence caused panic among Europe’s political leaders. Using Greece as a showcase, they vigorously enforced their so-called fiscal framework, i.e., the Stability and Growth Pact, SGP. The outcome was predictable but actually even worse than the expectations among most of us economists who witnessed it: Greece was subjected to a macroeconomic massacre. Six in ten young workers were unemployed, many social benefits programs cut by more than 50%, and one-quarter of the economy was wiped out.

Once the dust settled, the debate among both politicians and economists turned to the fiscal framework, specifically the SGP. There was no doubt anymore that the EU had created a terribly dysfunctional fiscal-policy tool.

The question since then has been: should the EU replace the Stability and Growth Pact with a new fiscal framework, or simply abolish the existing one and hope for the best?

Currently, the mainstream opinion appears to be that the SGP needs a reform or a replacement; a simple abolition is not on the agenda. To this point, back in December, the EU finance ministers reached an agreement on reforms to the SGP and the European Parliament held a vote in January on a reform proposal.

Not everyone agrees that reform is the way to go. On February 19th, Euractiv reported:

The European Left party (EL) wants to “abolish” the EU’s current fiscal rules to facilitate greater social and environmental spending, according to a draft electoral manifesto seen by Euractiv. The draft calls on the EU to “replace” the [SGP] … “with a new pact focusing on social and environmental restructuring, allowing for expansionary and counter-cyclical policies”.

Further down in their article, Euractiv cites the European Left president Walter Baier, who notes that his party prefers to emphasize “the poverty trap” and “the climate crisis” as well as “the desolate state of the public services” over budget balances and fiscal restraint.

It is easy to find economists who, based on a conventional misunderstanding of Keynesian macroeconomics, will argue that governments should engage in unrestrained deficit spending, especially in recessions. If we avoid the rabbit hole of economic theory, we can instead note that those who argue against fiscal rules and for more prevalent budget deficits are in fact breaking through open doors.

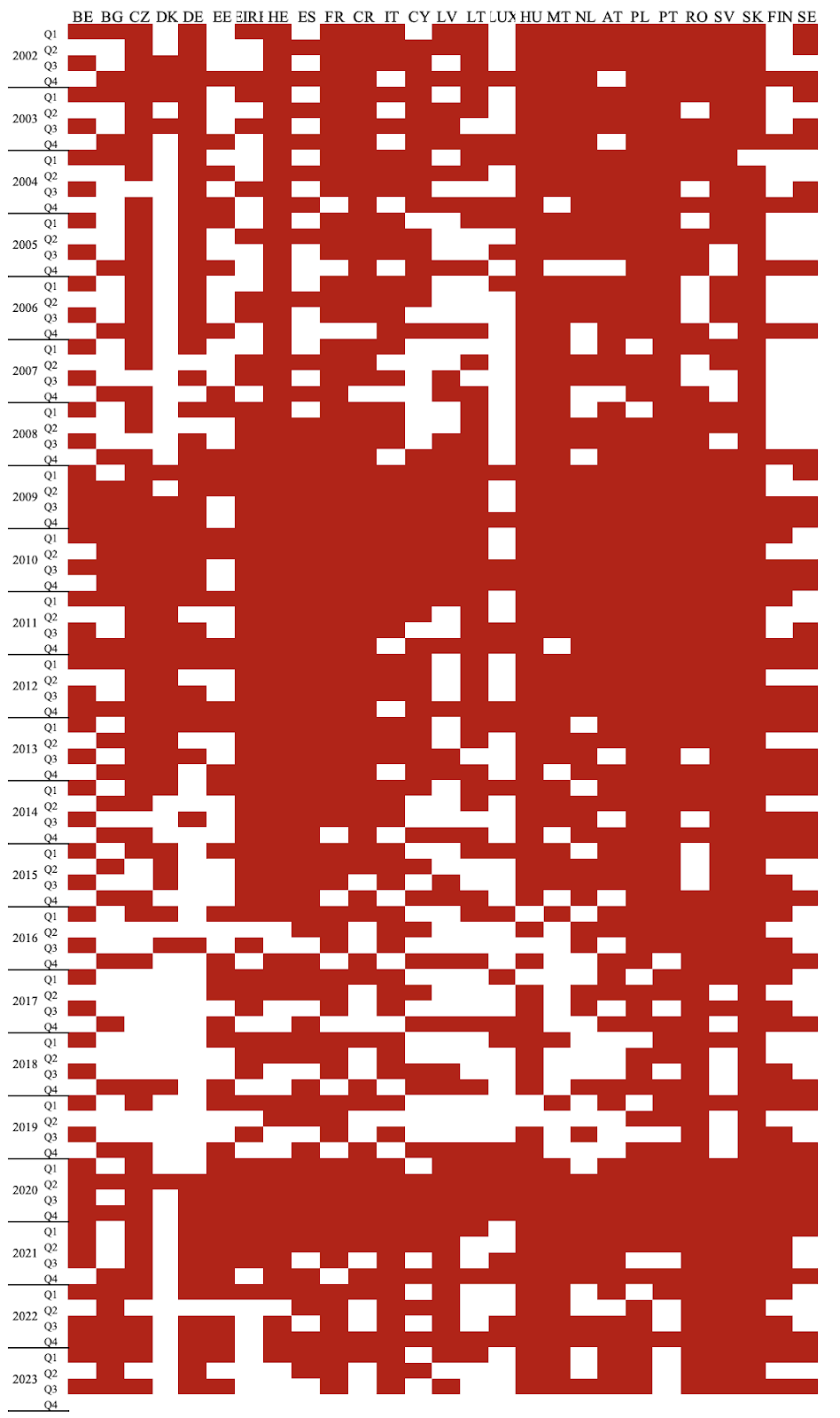

The state of the European economy is not the result of vigorous enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact. On the contrary, since the mid-2010s, it has either been suspended or the EU has avoided using it. Budget deficits are in fact normal in the EU, and not just in recessions: it is more difficult to find long periods without deficits than it is to find periods with them. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of deficits in consolidated government budgets in the current 27 EU member states, from 2002 through the third quarter of 2023. The columns represent the member states; each red square represents a quarter with a budget deficit, while each white square is a quarter with a budget surplus:

Figure 1

With the exception of 2016-2019, when it was relatively common with budgets in balance or surplus, the current members of the EU are plagued by chronic fiscal problems and have been so for more than 20 years. In other words, when the European Left effectively calls for the abolition of fiscal rules altogether, there is not much distance between reality and their ideal.

To be fair to the EL, though, their point goes one step further. They want to spend larger and more frequent budget deficits on economic redistribution, i.e., more social benefits for those who are classified as poor or otherwise needy. In doing so, the EL could make the ‘Keynesian’ argument that more money in the hands of the poor would increase overall economic activity. Households with lower incomes have a higher propensity to consume—the share of our disposable income that we spend—than those with high incomes. Therefore, the argument goes, economic redistribution pays for itself by elevating the overall economic activity in the country.

There are two problems here. The first is that if economic redistribution raised GDP growth this easily, then the most redistributive nations in the world, namely the Nordic countries, would be world-class economic leaders. They are not:

At best, Sweden and Denmark have kept up with the average growth rates among their EU fellow members.

To this point, the European Left could respond that they are not interested in economic growth. If we want to ‘save the climate’, they would contend, we cannot also strive to have a growing economy. As I explain in The Rise of Big Government, this argument has a long history on the Left. Thus far, it has drawn only scant responses from the rest of the ideological spectrum.

In addition to the fact that the economic logic behind the ‘green transition’ is flawed, it is worth pointing out that a stagnant—not to mention shrinking—economy has inadequate economic resources to develop the ‘solutions’ to the alleged climate problems that the Left wants to address. The more of a given cake they want to slice off for the ‘green transition’, the more people they are going to leave in the very poverty they claim to abhor.