In my analysis of the Russian GDP numbers recently, I explained that economic growth is stronger in Russia than in both the United States and Europe. There have been some questions about the veracity of these numbers, perhaps to be expected, given other questions about the veracity of Russian GDP data in general.

As I pointed out, the very fact that the International Monetary Fund—the source of the GDP data—published the numbers is in itself a quality mark. They are selective with national accounts numbers for Russia; the ones they publish have passed their quality checks and are therefore to be trusted at the same level as data they publish for any other country. However, a more profound explanation is needed of why it is reasonable to trust the IMF’s numbers.

Working with macroeconomics and national accounts—which includes GDP—on a daily basis, I regularly come across critics of the very concept of GDP. I have been told that it is “easy” to forge GDP numbers and that dictators always do that in order to look good.

It is worth noting that this criticism of the GDP concept never comes from other economists, but I also do not want to contest the point that a totalitarian government can forge any statistical information they want. On the contrary, it was well known that economic statistics coming out of, e.g., the Soviet Union were notoriously unreliable.

With that said, it is not the case that any government can simply dictate its GDP numbers and we have to either trust or not trust them. While a government agency can say whatever it wants, it cannot actually falsify its GDP to the point where we cannot see through the forgery. On the contrary, gross domestic product is actually one of the most difficult statistical variables to forge.

To begin with, GDP is measured in three separate ways. Most people have heard of GDP as the sum total of all spending in the economy. Textbooks in macroeconomics typically represent this GDP measurement method with the following equation,

Y = C + I + G + (X-Z)

where Y is GDP,

What most people do not know is that there are two more methods to measure GDP. One of them is called ‘the income approach’ and simply tallies up all the incomes made by households and businesses throughout the economy. This measurement method is the bedrock of statistics that is used to estimate revenue from income-based taxes, but it also helps us understand how the money spent in the economy creates income of various kinds.

The third GDP measurement is ‘the value-added approach,’ which adds up all the value created in the economy, in the production of both goods and services. Notably, many statistical agencies that produce GDP data omit this method, but the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis provides a whole section of data dedicated to value-added GDP.

Since this method accounts for all the inputs into production, it is also the most important one when it comes to checking the accuracy of GDP data in general. By looking at the use of certain inputs, we can estimate with a high level of accuracy the actual value being added in the production of both goods and services.

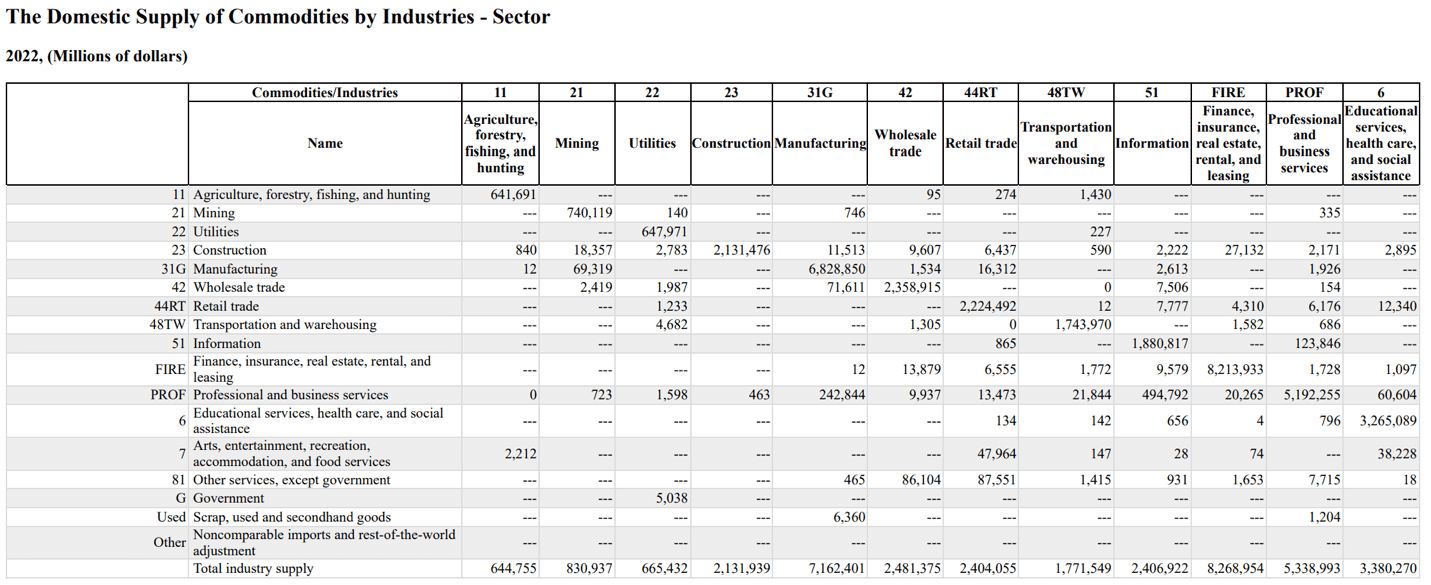

One of the tools related to value-added assessments is the so-called input-output matrix. It is strictly speaking not a value-added tool, but it can be used alongside traditional value calculations as a way to evaluate data quality. To get an idea of how intricate this matrix is, consider this snapshot of a very small part of the U.S. economy:

Table 1

When all the three measurements of GDP have been tallied up, they must by definition add up to the exact same number. Every euro spent in the economy eventually becomes someone’s income, and along the way pays for the value added by people and businesses producing the goods and services we spend money on.

The fact that all three GDP measurements must have the same sum total is an elementary but forceful checkpoint to see if the GDP data we are presented with is correct. Beyond those measurements, we have other statistics that are not part of GDP but can be used for checking those numbers. The best example is the labor market, which gives us employment and income numbers. We can use these numbers to check value-added GDP (employment) and income GDP.

If we doubt a country’s domestic GDP numbers, we can derive a fair amount of information from its foreign trade data. The neat thing about this statistical category is that it automatically has an independent verifier attached to it: every commodity or service imported to a country is logged as exports in another country. By tracking the latter, we can verify or falsify the former.

Many analysts realize the importance of foreign trade data, but they do not always use it accurately. For an embarrassing example, see this report on the Russian economy from 2022 by a group of analysts at Yale University.

Last but not least, the GDP number is not even the only number that matters when we want an aggregate picture of a nation’s economy. There is Gross National Product, Gross National Income, Net National Product, Net National Income…

All in all, the system that is used to measure a nation’s economy is so complex that it would take not only a group of PhD economists, but a large group of national accounts experts, to even begin forging the data. For an economy the size of Russia, there are billions of data entries that must be falsified if the system is to be consistent across all checks-and-balances mechanisms that are built into it. Just getting the spending, value-added, and income measurements to add up, is a daunting task for a national accounts forger.

That is not to say all GDP numbers are reliable. When there is insufficient data, or when the data collection methods are not up to standard, reputable statistics agencies simply refuse to publish them. As mentioned earlier, this means that when they do publish GDP data, we can take those numbers at face value.