At its meeting this week, the Federal Reserve is widely expected to keep its policy-setting federal funds rate unchanged. This is good from a monetary policy viewpoint, but it is not good news for Congress. With less than two weeks to go to the halfway point of the 2024 fiscal year, the federal government has already borrowed $1.01 trillion since October 1st.

This borrowed money is not even enough to pay the annualized interest on the debt, which, as of March 18th, stood at $1.08 trillion. Once that is paid, it is time to cover all other items in the federal budget, which Congress does not have enough tax revenue to pay for.

It is not exactly a secret that the cost of the U.S. debt is gradually overwhelming the federal budget. The latest estimate from the Office of Management and Budget—an outfit under the White House—puts the cost of interest on the debt as second only to Social Security:

Figure 1

This year, Congress is expected to spend over 10% more on interest for its debt than on national defense. However, the most serious message from Figure 1 is that the red column is likely to shoot up rapidly in the near future. The red column ends at $1,oo7 billion, or $1.007 trillion; this estimate is based on the premise that the debt will not exceed its current level, or, alternatively, that interest rates will start falling soon and therefore halt the ongoing rise in interest rate costs.

The number reported by the OMB is close to the $1.08 trillion that my model estimates; it is unclear if the OMB number factors in the steady growth of the debt or the constant changes in interest rates at auctions.

More than likely, at the end of the 2024 fiscal year, Congress will find that the interest cost actually ran notably higher than the estimate reported here. The reason is found in the combination of, on the one hand, interest rates and Treasury yields and, on the other hand, the Treasury’s preferred composition of the debt.

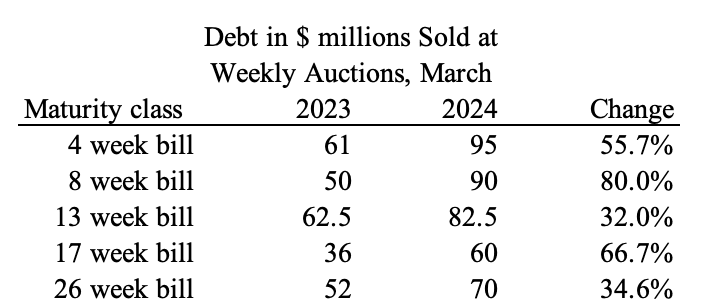

Before we get to the composition part, let us take a brief look at how the Treasury has developed its sales of debt generally. There has been an expansion of debt sold under practically every maturity of Treasury securities; Table 1 compares the volumes of debt sold under all the maturities where new debt is auctioned every week. Compared to a year ago, the weekly auctions are significantly larger, especially under the shorter maturities:

Table 1

In March 2023, the weekly auctions of these five maturity classes sold just over $250 billion worth of Treasury securities; currently, the same auctions sell almost $400 billion in new debt.

Debt auctions have also grown under mid-range maturities, a.k.a., 2-10-year Treasury notes, where auctions are held monthly. In one year, the volumes sold under the 2- and 5-year notes have gone up by 55%; the increase is roughly one-third under the 3- and 7-year notes. The volume sold under the benchmark 10-year note has increased by almost 15%.

The only maturity where the Treasury has reduced its auction sales is under the 20-year bond; the net increase for 20- and 30-year bonds together is 3.5%.

All in all, the sales of debt have expanded the most toward the shorter end of the maturity spectrum. Looking specifically at the 2024 fiscal year, the Treasury has covered 78% of its borrowing to date by selling bills with a maturity date in one year or less.

This is a debt management strategy that becomes peculiar when we take into account the fact that interest rates are higher on shorter-term debt securities. As an example, in one weekly auction, the Treasury sells more debt under its 13-week bill than it does at its monthly auctions of 10-year notes and 20- and 30-year bonds—combined. They do this despite the fact that the interest that the Treasury has to commit to at the 13-week auctions is approximately one full percentage point higher than they are on average at the 10-, 20-, and 30-year securities.

To get an idea of what this means: all other things equal, if for one year the Treasury could sell all the debt in Table 1 at the same interest rates it pays on its longest securities, then taxpayers would save $4 billion.

This is not peanuts—on the contrary, the numbers add up when we expand this analysis to the rest of the debt. There is, of course, a caveat: a drastic increase in the supply of long-term debt would require a major shift in investor preferences, i.e., demand would have to follow supply. If it does not, then the price of each security would drop, which would raise the interest rate. That, in turn, would moot the point of shifting debt from short- to long-term maturities.

However, this is not just a theoretical exercise. If the Treasury had planned with a long-term perspective already when it began drastically expanding its debt sales during the pandemic, it would not be in a situation where the average interest on its total stock of debt continues to tick up. Likewise, if the Treasury actually implements the plan it mentioned in January to increase debt sales with longer maturities, with patience it could achieve the same goal